Untitled (Head in Sand – Kunsthalle Bielefeld – Created for the exhibition: “Ars Viva – Sculpture and installations by prize-winners selected by the Cultural Committee of German Business within the Federation of German Industries BDI e.V.” – 1981), [2012], 1982, was conceptually initiated 30 years ago and has been integrated since 2012, in its final version, into Frankfurter Block.

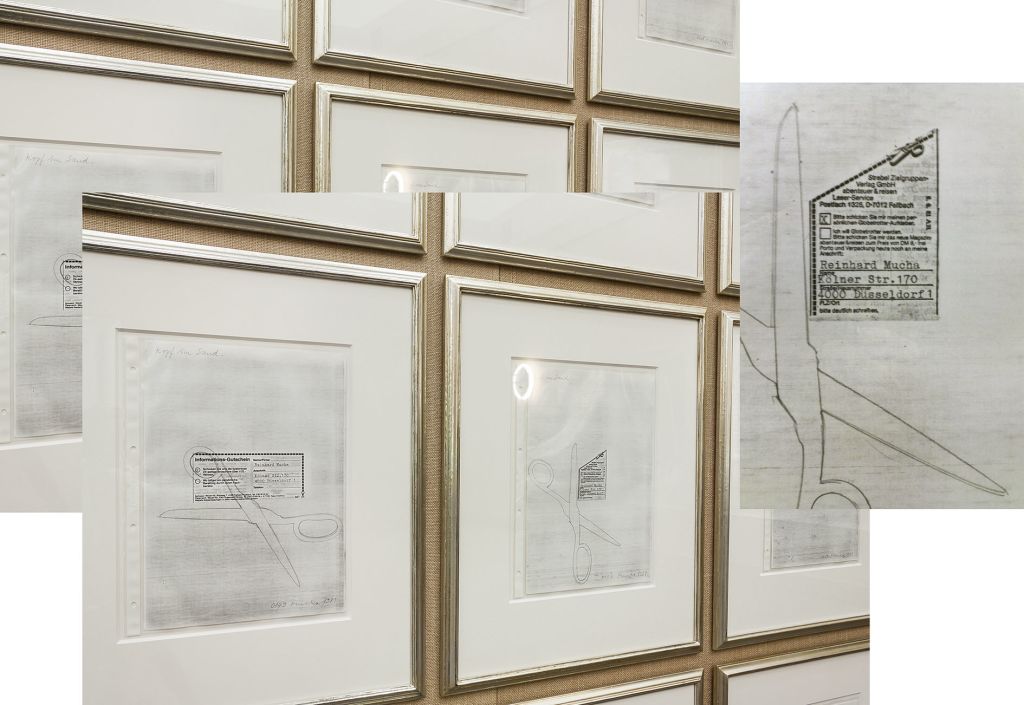

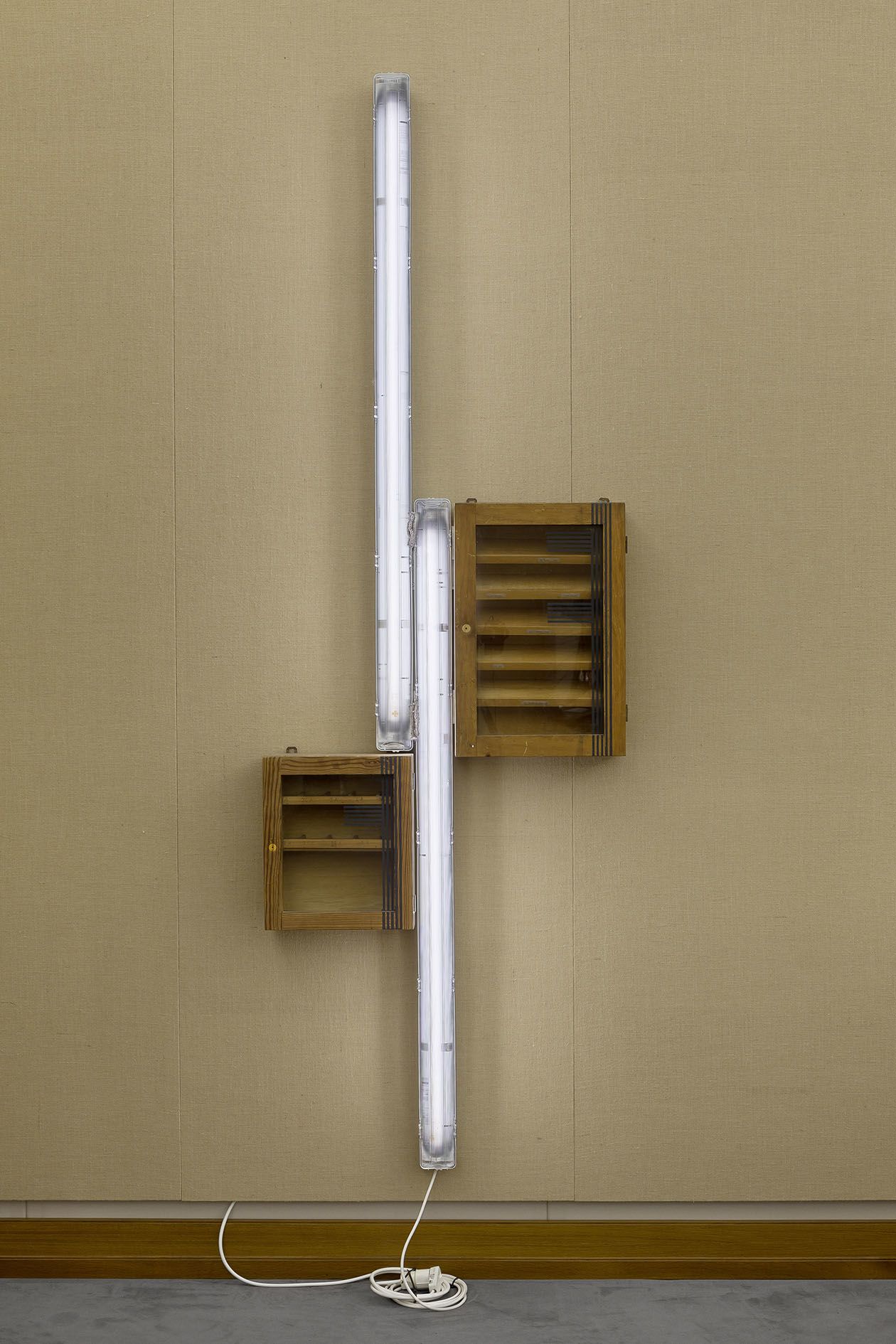

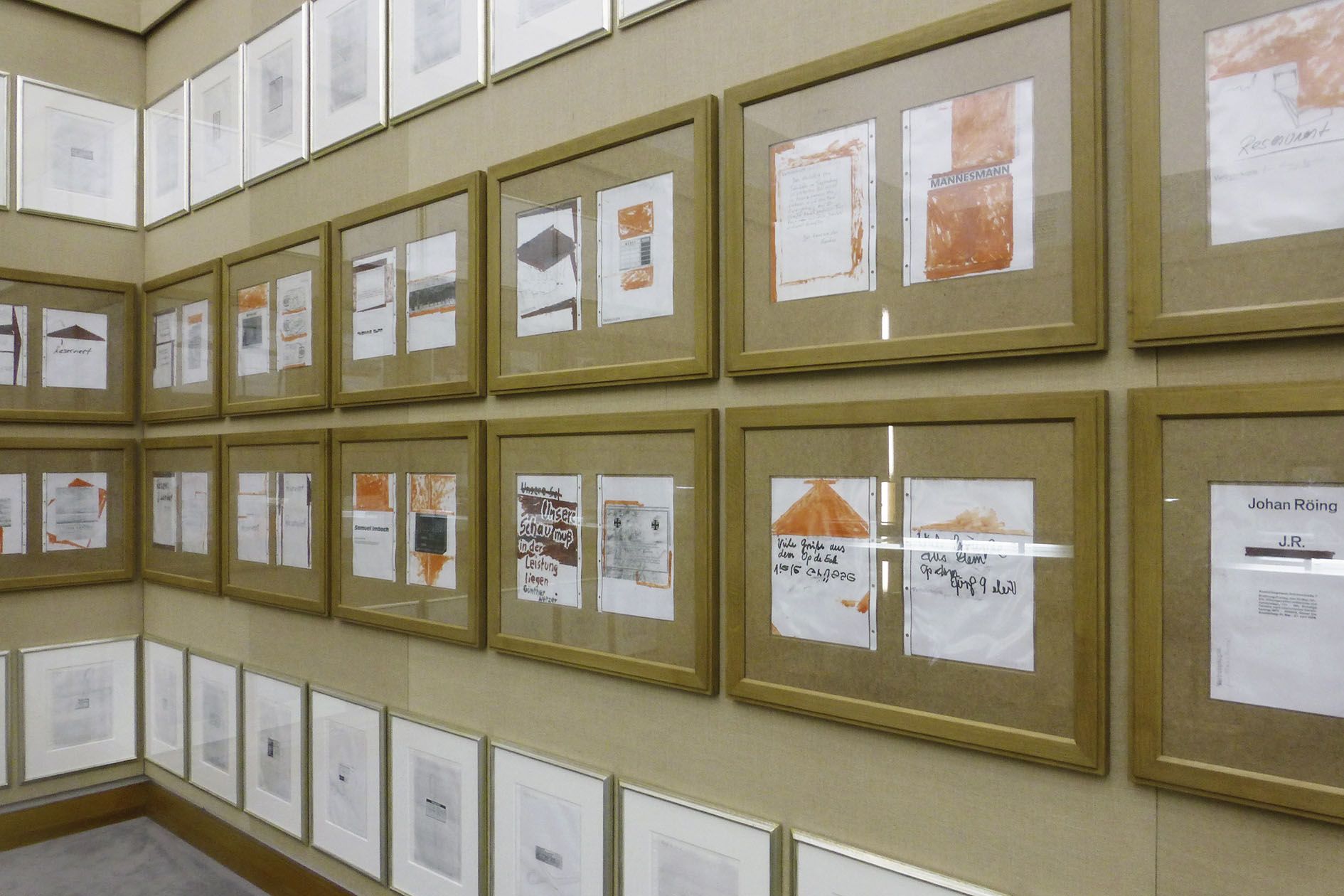

Several hundred coupons cut out from magazines, to request information material from all kinds of businesses, were filled in by Mucha with his address and sent off. As early as 1981, in an exhibition at Kunsthalle Bielefeld, 99 photocopies of the coupons were furnished with framing relating to the Kunsthalle’s architecture. The photocopies were hung like precious miniatures on one of the museum’s linen-covered walls, adjacent to which were approximately 600 unopened letters of reply piled up and presented in a table display case. The proliferation of personal data together with the arbitrariness of the bundles of information generated in this manner, thwarted any customer or personal profile the advertising businesses and institutions may have been seeking. In 2012 in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Christoph Schütte described it as an “essentially analogue work, which even in the digital era of Facebook has lost none of its (socio-political) relevance.” In 1982, in “Junge Kunst in Deutschland – Privat gefördert”, an exhibition of young German artists who had been the recipients of privately supported grants, which was shown at Kölnischer Kunstverein, Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and Lenbachhaus in Munich, Mucha now stowed the 99 framed coupons as well as the unopened letters in four display cases. Three photographic views of the installation in Bielefeld were also included and the illuminated display cases were placed on 16 foot stools, which in their both anarchic and playful arrangement became substitutes, quasi placeholders, for the 16 young grant recipients being exhibited, symbolically undermining the patrons well-meaning intentions for the event. It was only in 2012 that four monitors, which are hanging in racks under the display cases, showing video animations of photographs of the three itinerations of the exhibition from 1982/83, supplemented this ensemble. Against the background of a soundtrack of the noise made by young skateboarders, the filmic representation of the stools placed underneath the display cases also counteracts any smoothly coherent museological staging, as well as commenting in a humorous manner on the subject matter and background of the entire exhibition tour.

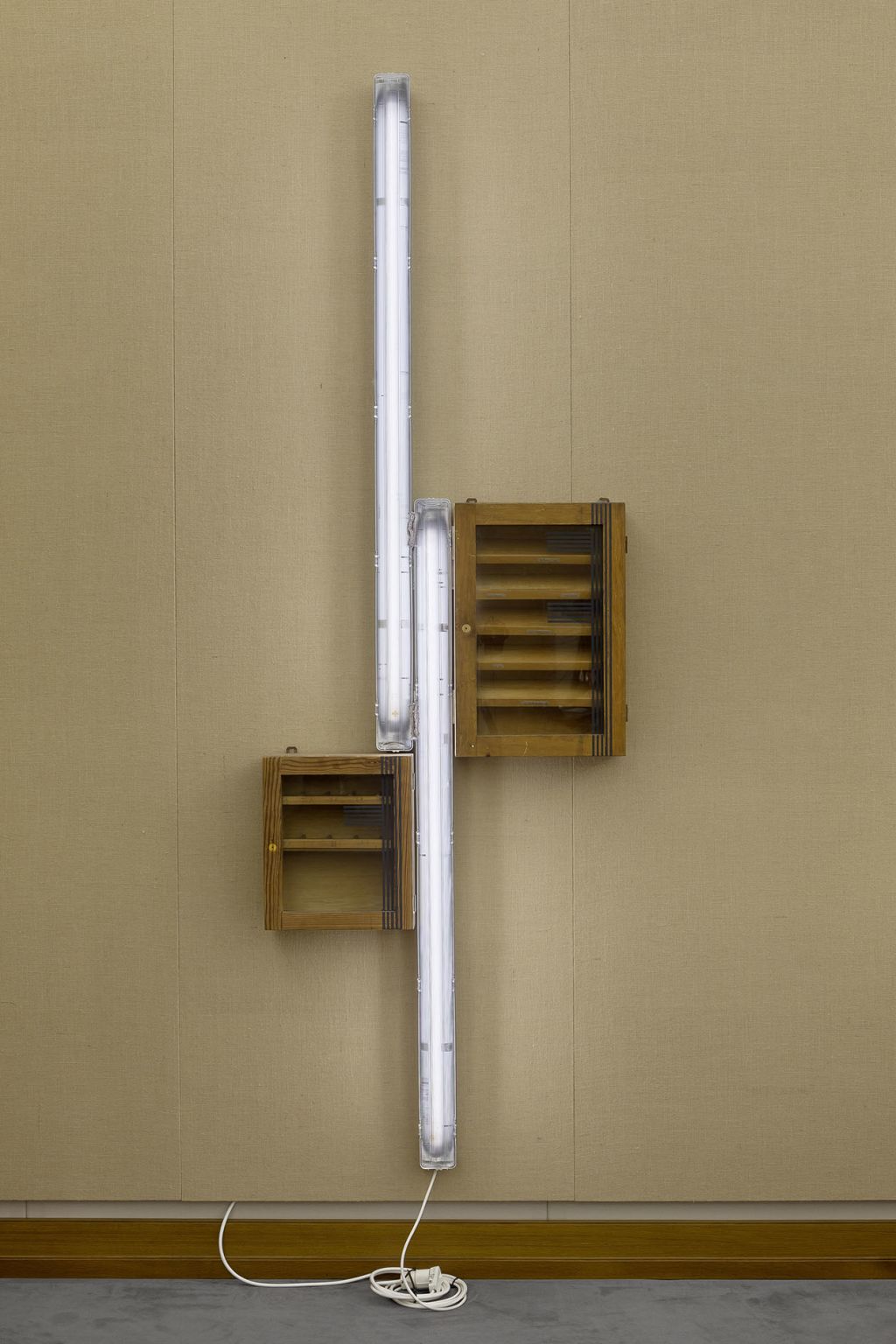

[Capriccio] – How a Dead Hare Operates with Pictures, 2012, not only alludes to Beuys, but also to the everyday routines and arrangements of museums and exhibition organisation in general: the glass display case houses two white plinths each positioned horizontally on dollies, on the floor in front, a blanket for packing furniture from the art transport company “Hasenkamp – Internationale Spedition” is rolled up and wedged between the legs of an upside-down foot stool, as the cargo of a convoy of two hand carts and a dolly.

Mucha’s time as an art college student is the subject of the work The Clever Servant (Ohne Titel – Staatliche Kunstakademie – Düsseldorf – 1981), 2002. Rose-Maria Gropp commented on it in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: “Behind a four meter wide glass panel, in old-fashioned typography, is the fairy tale of the same name by the Brothers Grimm about a servant who finds three blackbirds in a field instead of searching for his master’s cow. It is accompanied by a looped video of a young man somersaulting about, a refusal of mastery and following transformed into a video, against a soundtrack of noise.”

In the two-part ensemble Knowing whereby, not knowing wherewith. Knowing whereto, not knowing whereat., [2007], 1983, the artist’s hand, that he photographed himself, arranges empty chocolate boxes on a mirror as if on a stage. As shiny shimmering “box girders”, as consumer packaging of seemingly individual form, these deep-drawn plastic molds reveal themselves to be standardizedly glossy, deceptive packaging which in a metaphorical sense effortlessly captures the escapism involved in any act of creative self-fulfilment.

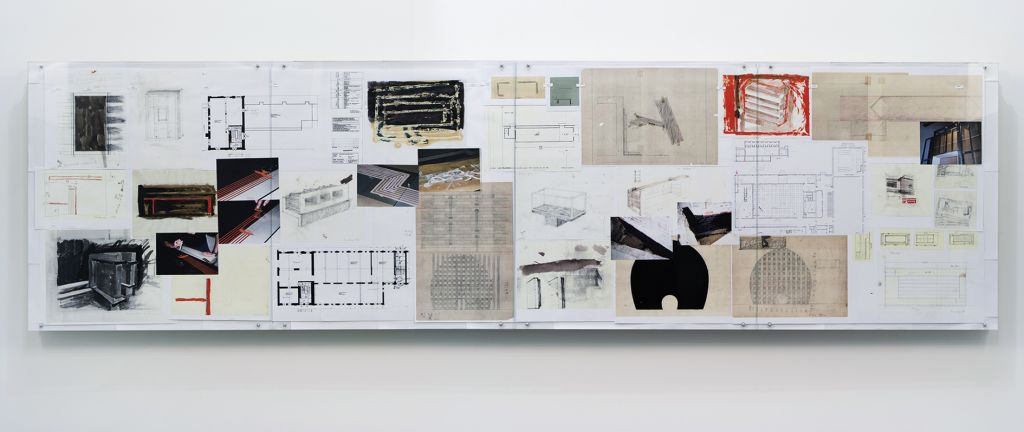

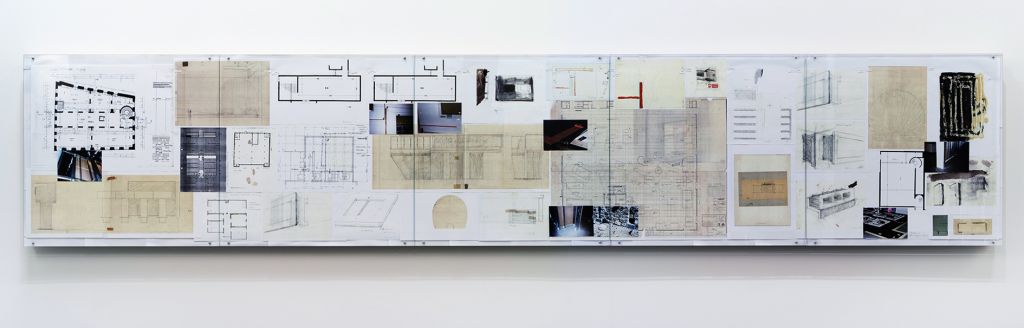

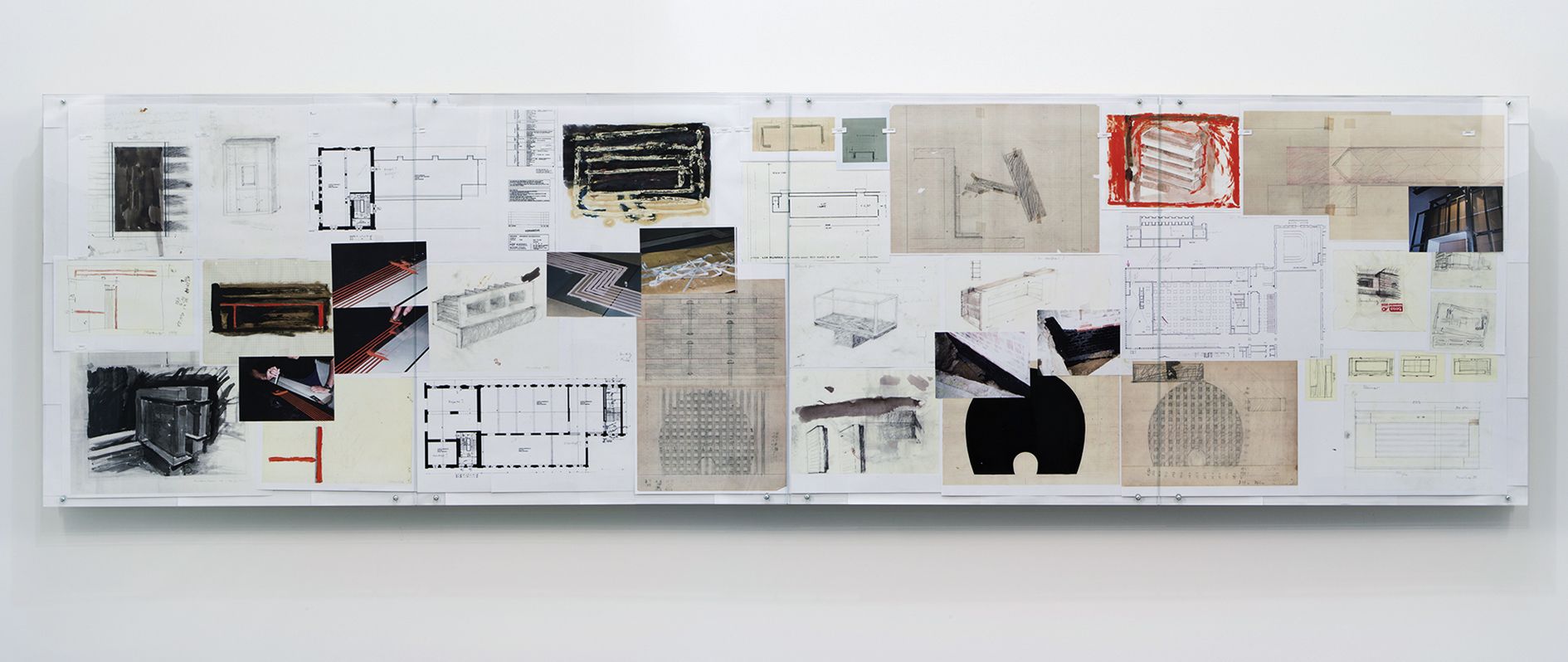

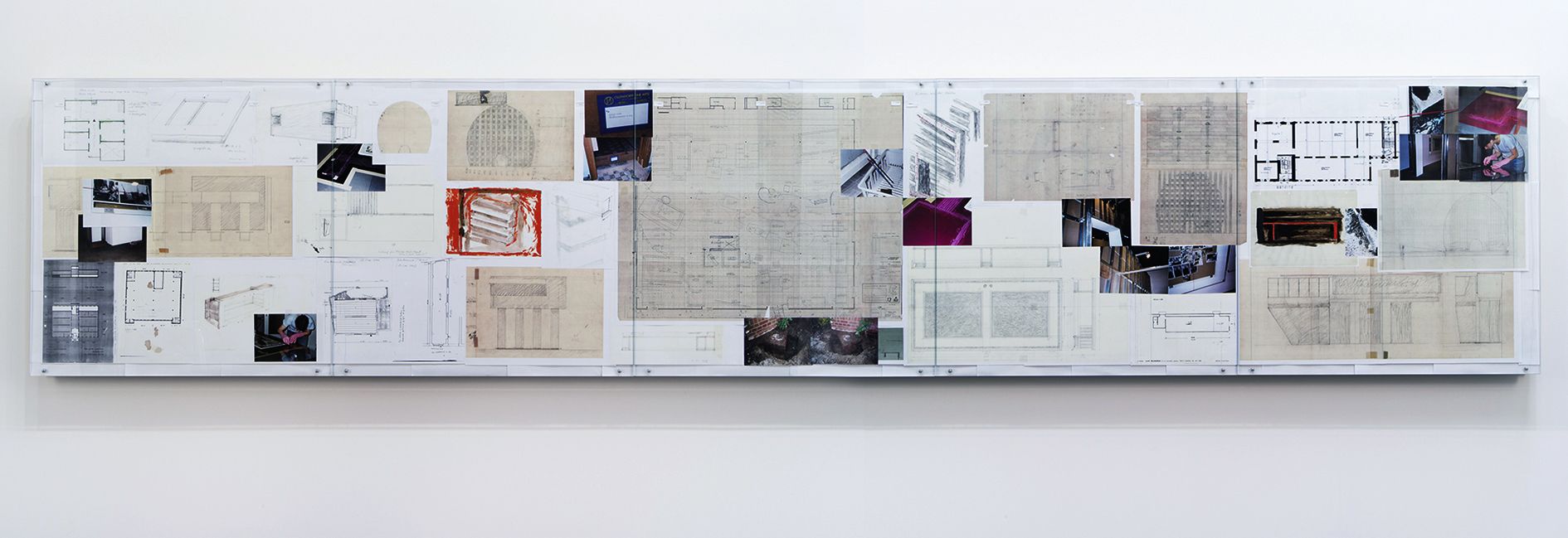

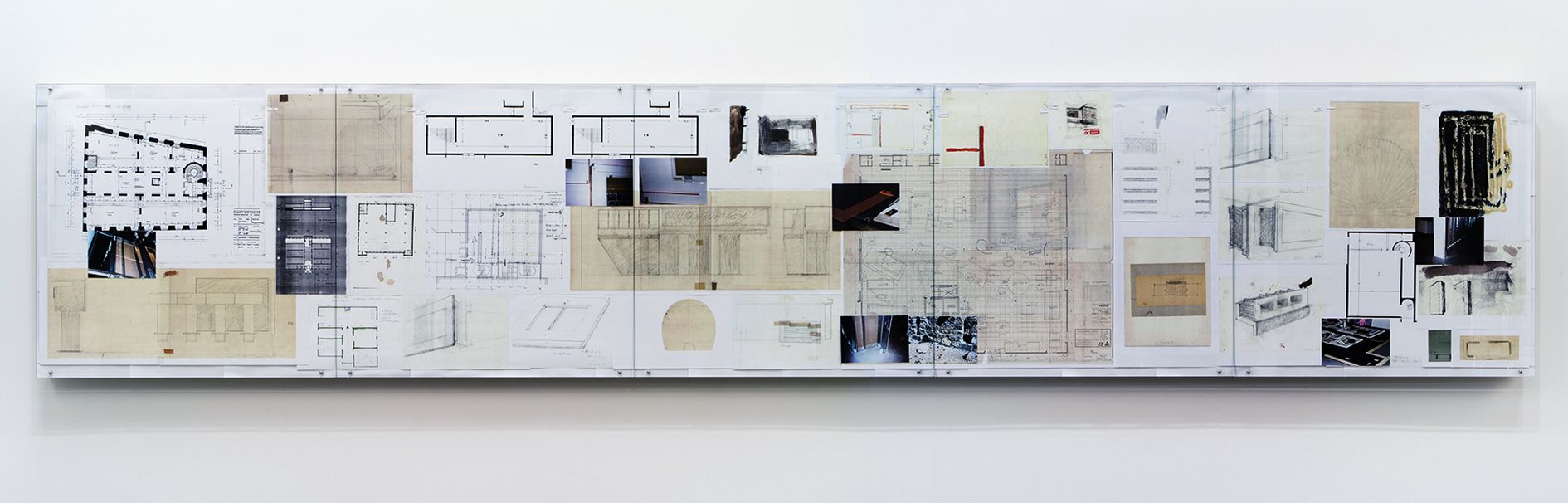

The box girder or “Hohlkasten”, a technical term from bridge building, is a metaphor archetypical of Mucha’s thinking and also plays a fundamental role in Untitled (MILCH) – 1:1 model of the eliminated competition entry to “Kunst am Bau – Eingeladener Wettbewerb” for Volkswagen University Library of Berlin Institute of Technology (TU) and Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) 2004, [2014], 1979, an almost eight meter long sculpture. The process of realising this piece is simultaneously an exemplary demonstration of creation over an extended period of time: from the initial idea in 1979, via its proposal as a tender for art in architecture in the central atrium of the Volkswagen University Library Berlin in 2004, to it being executed for the first time for the exhibition at Sprüth Magers in 2014 – and, not least, it is a graphic evocation of vivid thoughts concerning the university as Alma Mater, the nurturing mother.

The reference to Donald Judd’s earliest three-dimensional work, a pictorial object from 1961, in which Judd integrated a rectangular cake tin from aluminium sheeting, is recognisable in Seelze [2014], 2012. The similarly rectangular but albeit larger zinc tub, a found object, is surrounded and supported by a steel construction like a contemporary multifunctional arena and is closed off towards the viewer by a reflective glass panel, the reverse side painted with grey lines.

In Welt am Sonntag 2012 Hans-Joachim Müller spoke of Mucha’s “individual manner of sensuous thoughtfulness. […] When Mucha makes art, he does not produce tangible proximity, but instead distance that is thought.” In addition to this aspect of sensuousness, Müller emphasised the temporal element: “If this work is unified by one thing, then it is the compression of time to which it constantly returns. Mucha impedes the flow of time, thickens it with his home-made preservatives […] the artistic attitude accordingly becomes always a sort of active resistance to the centrifugal forces of history.”