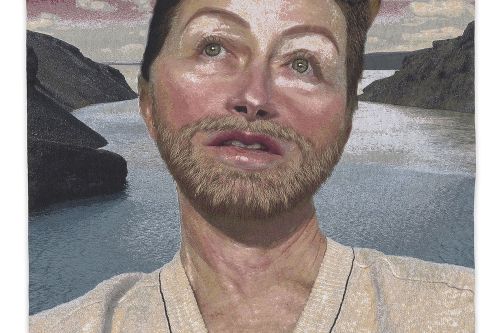

Cindy Sherman (*1954 in New Jersey) lives and works in New York. Selected solo exhibitions include Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens (2024), Fotomuseum Antwerp (2024), AroS, Aarhus (2023), Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (2021), National Portrait Gallery, London (2019), Fosun Foundation, Shanghai (2018), The Broad, Los Angeles (2016), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (all 2012), Dallas Museum of Art (2013), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin (both 2007), Kunsthaus Bregenz, Jeu de Paume, Paris (both 2006) and Serpentine Gallery, London (2003). Selected group exhibitions include Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2025), FOMU Fotomuseum, Antwerp (2024), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Louisiana (2024), Neue National Gallery, Berlin (2023), Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul (2021), Seattle Art Museum, Seattle (2020), Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich (2019), Hayward Gallery, London (2018), National Portrait Gallery, London, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (both 2017), National Gallery of Art, Washington (2016), Tate Modern, London (2015), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2012) and MUMOK, Vienna (2011). She participated in the 40th, 46th, 54th and 55th Venice Biennale.

| 2020 |

Wolf Prize |

| 2019 |

Max-Beckmann-Prize |

| 2017 |

The 100 Most Influential People (Time Magazine) |

| 2016 |

Praemium Imperiale |

| 2014 |

Centennial Medal, American Academy in Rome |

| 2012 |

Roswitha Haftmann Prize |

| 2011 |

Archives of American Art Medal |

| 2010 |

Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Arts |

| 2009 |

National Artist Honoree, The Anderson Ranch Arts Centre |

| 2005 |

American Academy of Arts and Letters Award Honoree at New Museum of Contemporary Art Annual Benefit Gala |

| 2003 |

American Academy of Arts and Sciences Award |

| 2002 |

The National Arts Award |

| 2001 |

New York State Governor’s Arts Awards |

| 2000 |

The Hasselblad Foundation |

|

U.S. Art Critics Association |

| 1999 |

Goslar Kaiserring Prize |

| 1997 |

Wolfgang-Hahn-Preis (Gesellschaft für Moderne Kunst am Museum Ludwig) |

| 1995 |

John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation |

| 1993 |

Larry Aldrich Foundation Award, Connecticut |

| 1989 |

Skowhegan Medal for Photography, Maine |

| 1983 |

John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship |

| 1977 |

National Endowment for the Arts |

| Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY |

| Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney |

| Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto |

| Art Institute of Chicago |

| Australian National Gallery, Canberra |

| Baltimore Museum of Art |

| Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh |

| Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris |

| Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid |

| Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. |

| Dallas Museum of Fine Arts |

| Des Moines Art Center |

| Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin |

| Israeli Museum, Israel |

| Kunsthaus, Zurich |

| Kunsthalle Hamburg |

| Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg |

| Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

| Louisana Museum, Humlebaek |

| Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

| Moderna Museet, Stockholm |

| Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth |

| Musée d'Art Contemporain de Montréal |

| Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam |

| Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna |

| Museum Folkwang, Essen |

| Museum Ludwig, Cologne |

| Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh |

| Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago |

| Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki |

| Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles |

| Museum of Contemporary Art, Luxembourg |

| Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

| Museum of Fine Arts, Houston |

| Museum of Modern Art, New York |

| Museum of Modern Art, Oslo |

| Philadelphia Museum of Art |

| Rijksmuseum Kroller-Muller, Otterlo |

| San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

| Salomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York |

| Sprengel Museum, Hanover |

| St. Louis Art Museum |

| Staatsgalerie Stuttgart |

| Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main |

| Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam |

| Tamayo Museum, Mexico City |

| Tate, London |

| Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography |

| Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

| Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford Walker Art Center, Minneapolis |

| Whitney Museum of American Art, New York |