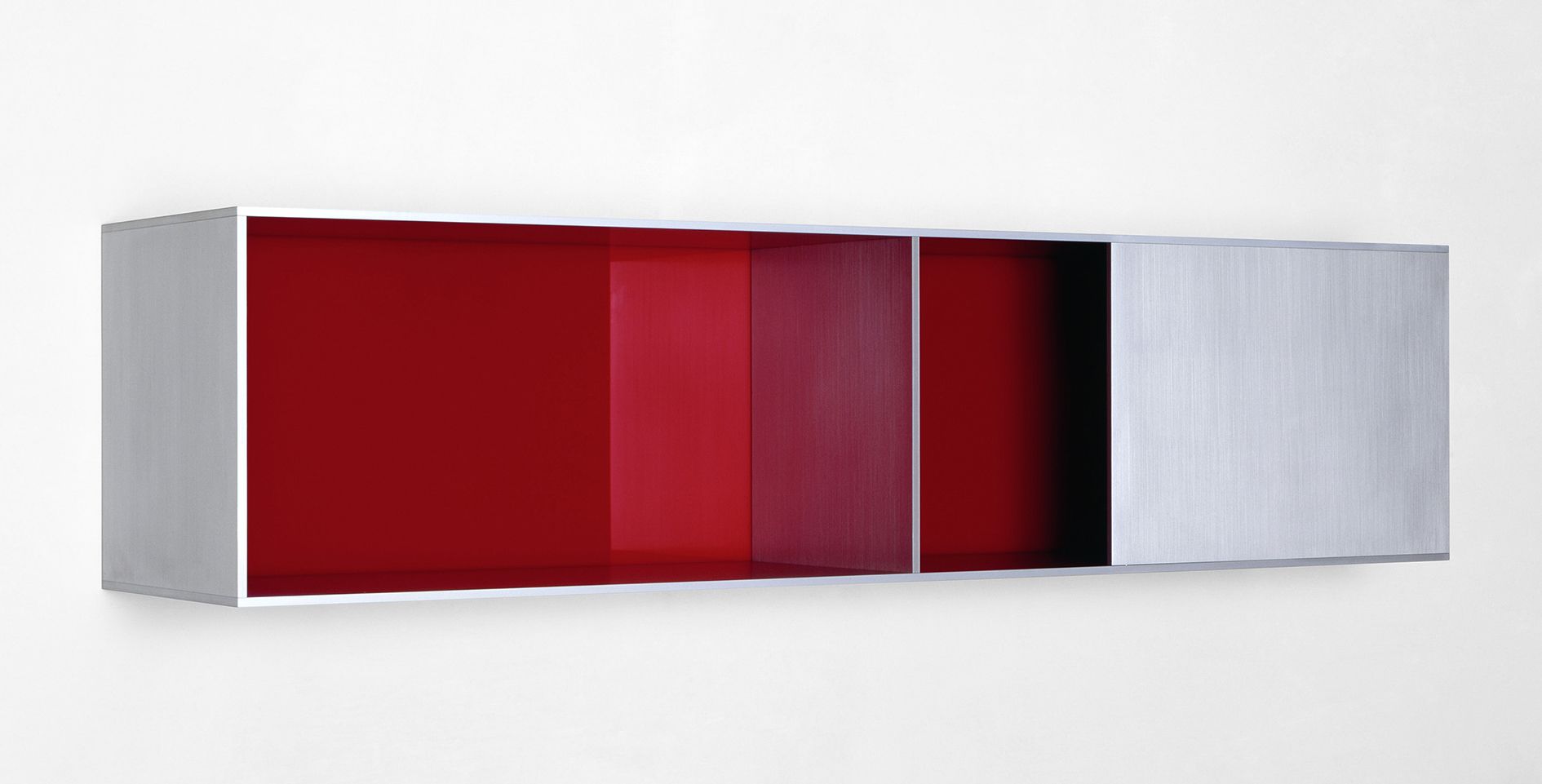

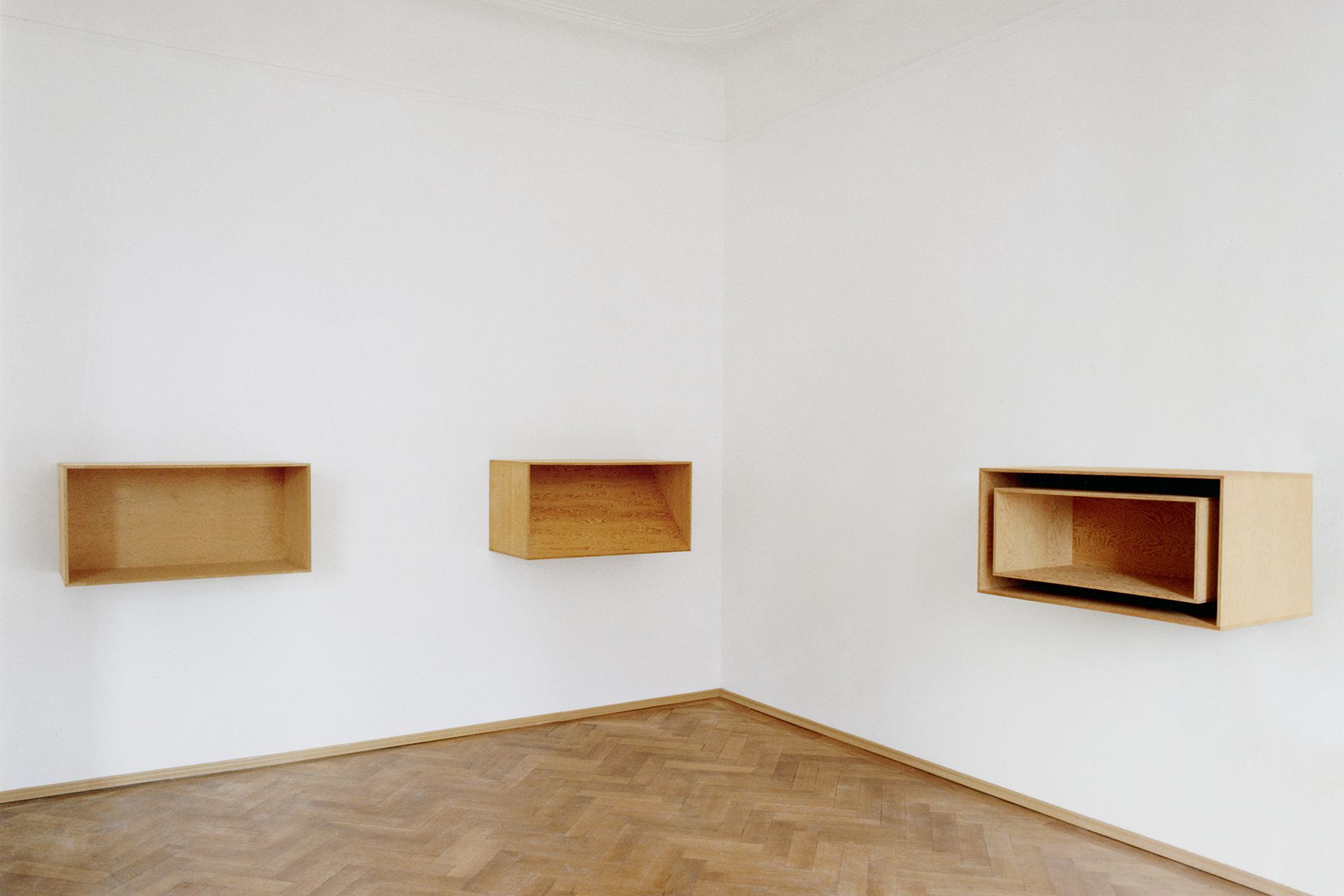

Donald Judd (1928–1994) is a landmark figure in twentieth-century American art who revolutionized our understanding of sculpture. Despite a lifelong antipathy to the term minimalism, he is considered a pioneer, theorist and key representative of the movement. His iconic objects were based on a few basic geometric forms. They were executed in a variety of materials and colors and evoke an astonishing range of atmospheres, spatial presences and aesthetic experiences. Judd lived in New York City and Marfa, Texas, where he founded the Chinati Foundation to preserve both his own work and that of other artists.

Mondi Possibili

Henni Alftan, John Baldessari, Cao Fei, Thomas Demand, Thea Djordjadze, Lucy Dodd, Robert Elfgen, Peter Fischli David Weiss, Sylvie Fleury, Jenny Holzer, Donald Judd, Karen Kilimnik, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, David Ostrowski, Michail Pirgelis, Sterling Ruby, Thomas Scheibitz, Andreas Schulze, Hyun-Sook Song, Robert Therrien, Rosemarie Trockel, Kaari Upson, Andrea Zittel

August 31–September 14, 2023

Seoul

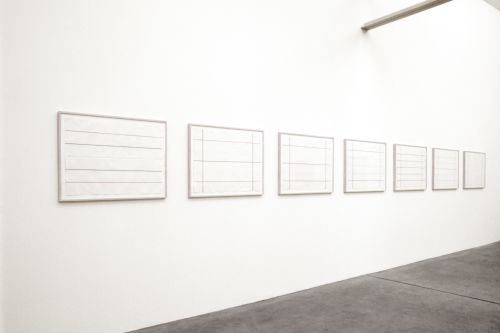

Mondi Possibili highlights the interplay between art and design and explores the many ways in which experimentation with material, technique and scale can reveal the hidden narratives, quiet drama and humor in the everyday items that furnish our lives as well as our imaginations. Connected through a paradigm of the possible, all artworks on show examine familiar objects – citing, celebrating, adapting or appropriating them – offering surprising, playful or unsettling approaches that open up a range of “possible worlds.” This will be the fourth edition of Sprüth Magers’ Mondi Possibili – first titled by Pasquale Leccese – showcasing significant themes in the selected artists’ works as well as the gallery’s longstanding heritage. Its three previous iterations were presented in 1989, 2006 and 2007 in Cologne, where the gallery’s history is firmly rooted, and art and design have intersected for many decades.

Read more