Darboven’s interest in representing the mechanisms of time emerged early in her career, manifesting in the form of diagram compositions, columns of numbers and constructivist drawings. Her time in New York exposed her to the work of artists including Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner and Carl Andre. Darboven thus became part of the scene that laid the theoretical and aesthetic groundwork for conceptual and minimal art—eschewing notions of artistic subjectivity, advancing the principle of serialism, and insisting on the viewer’s perception as a substantial, participatory force in the creation of the artwork itself.

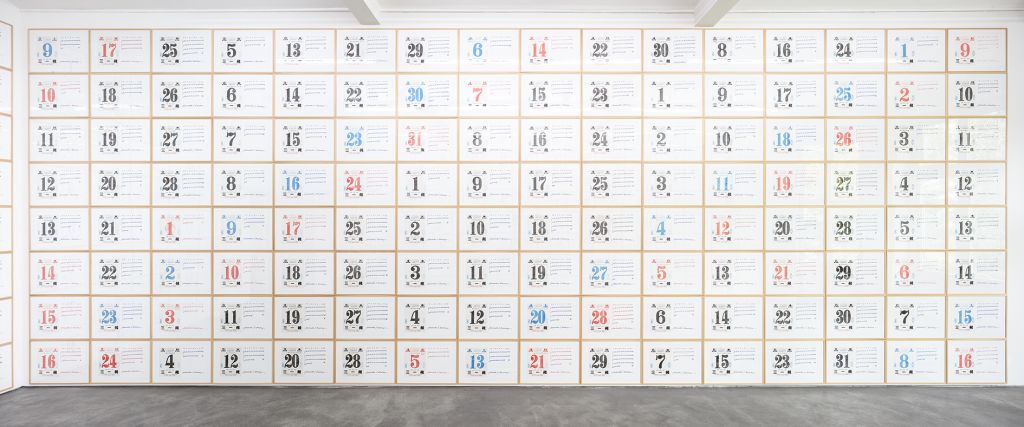

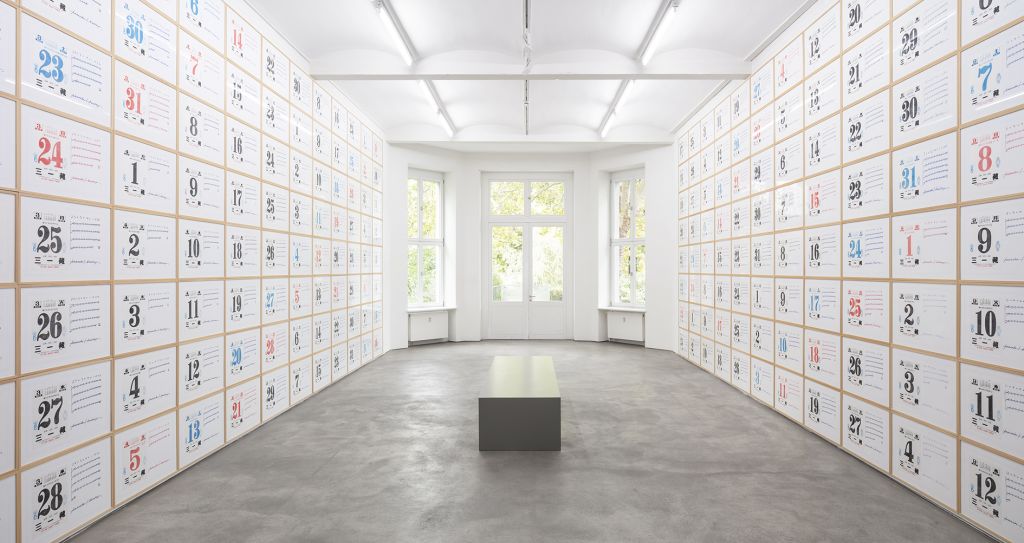

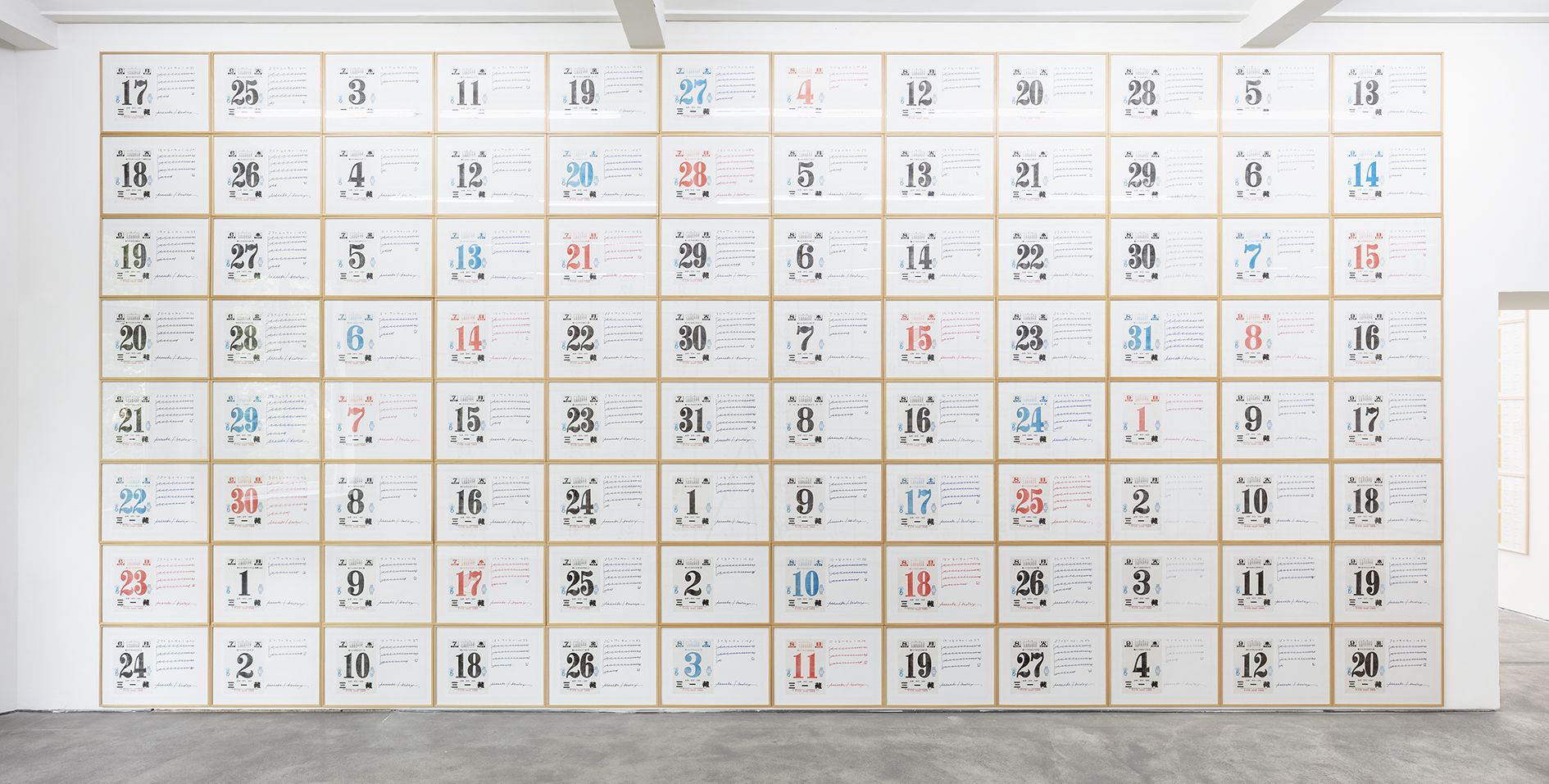

Darboven embodied LeWitt’s idea of the artist operating “merely as a clerk cataloging the results of the premise” more consistently than any other conceptual artist of the day. She developed a handwritten notation system that recalled digital datasets, evoking the aesthetics of the early computer age. Within that notation system Darboven explored the reality of the calendar as a supposedly objective instrument for measuring time. She came up with a specific way of doing cross-sum calculations that she used to convert the numbers of a given calendar date into individual digits. Afterwards, she converted those digits into increasingly elaborate visual form of writing that employed vectors, boxes or wavy lines. It was through this act of writing that she chronicled her own lifetime, which she devoted almost entirely to her work. This time-writing resulted in works such as Weltansichten 00–99 (1975–80), which consist of hundreds, sometimes thousands of identically framed compositions on paper, hanging in enormous grids that blanket the walls of entire exhibition venues.

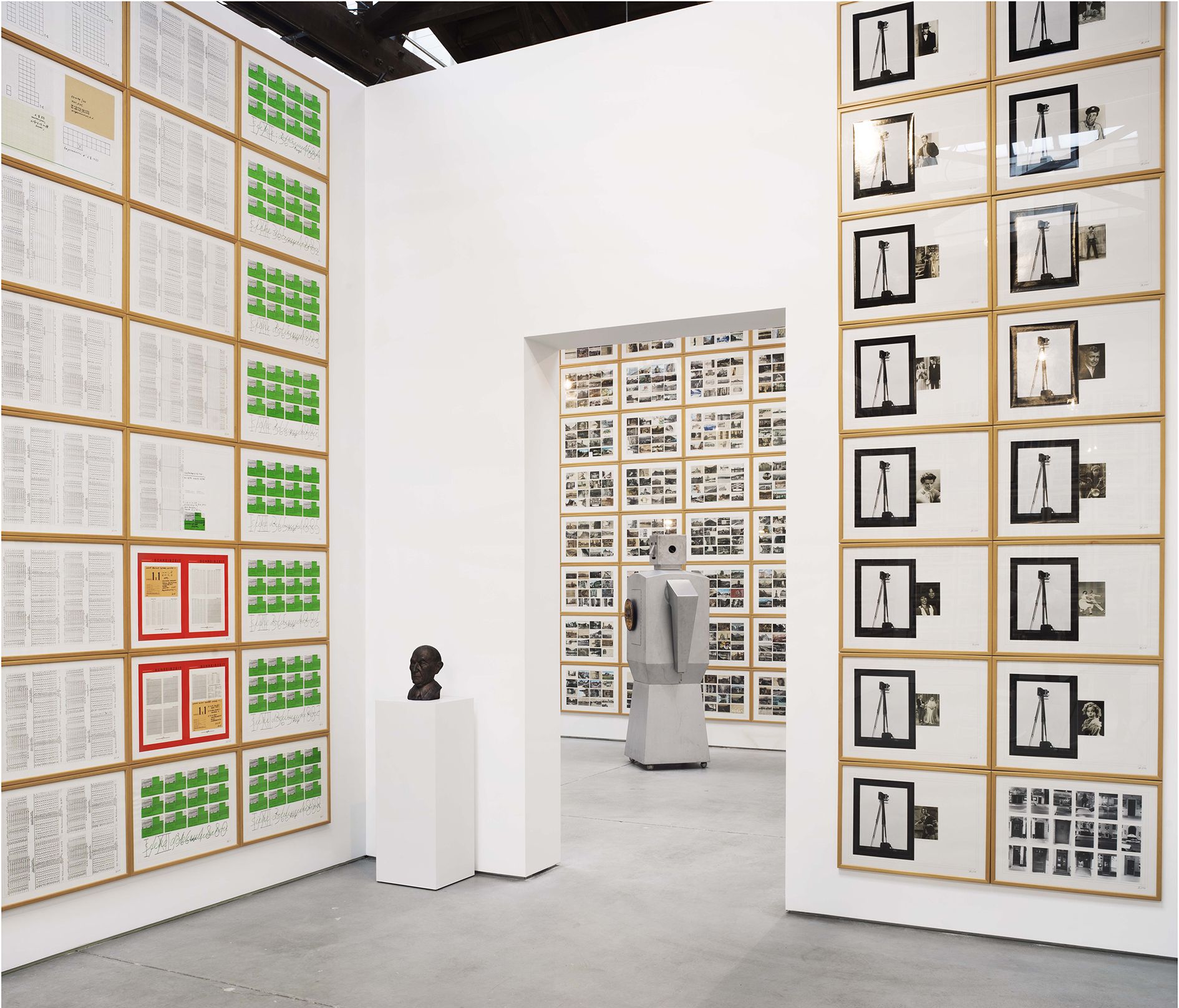

Darboven’s later, even more monumental works including Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (1980–83) shifted focus to the temporal present as a phenomenon that always already contains both the past and future. She devoted weeks to producing handwritten copies of texts such as Homer’s Odyssey and Sartre’s The Words, and invented an elaborate system to convert many of her date drawings into scores for hypnotic pieces of music. Expansive installations feature a combination of calendar works, photos, postcards, school materials, musical instruments, store mannequins, and other found objects or images. Darboven was convinced of the principles of classical Enlightenment and gestured to ideas of a universal education. She offered connections between historical events, epistemological detritus, and private moments, often distinguishing herself as a keen observer of contemporary politics.

In attempting to decipher Hanne Darboven’s works, viewers become cognizant of more than just the limited nature of their own lifetimes. They also become conscious of the fact that there is no such thing as “objective time” and that time, in human perception, can only ever be an amalgamation of feelings, memories and thoughts. For Darboven it is no linear process, but an impenetrable, highly subjective plexus of parallel phenomena.