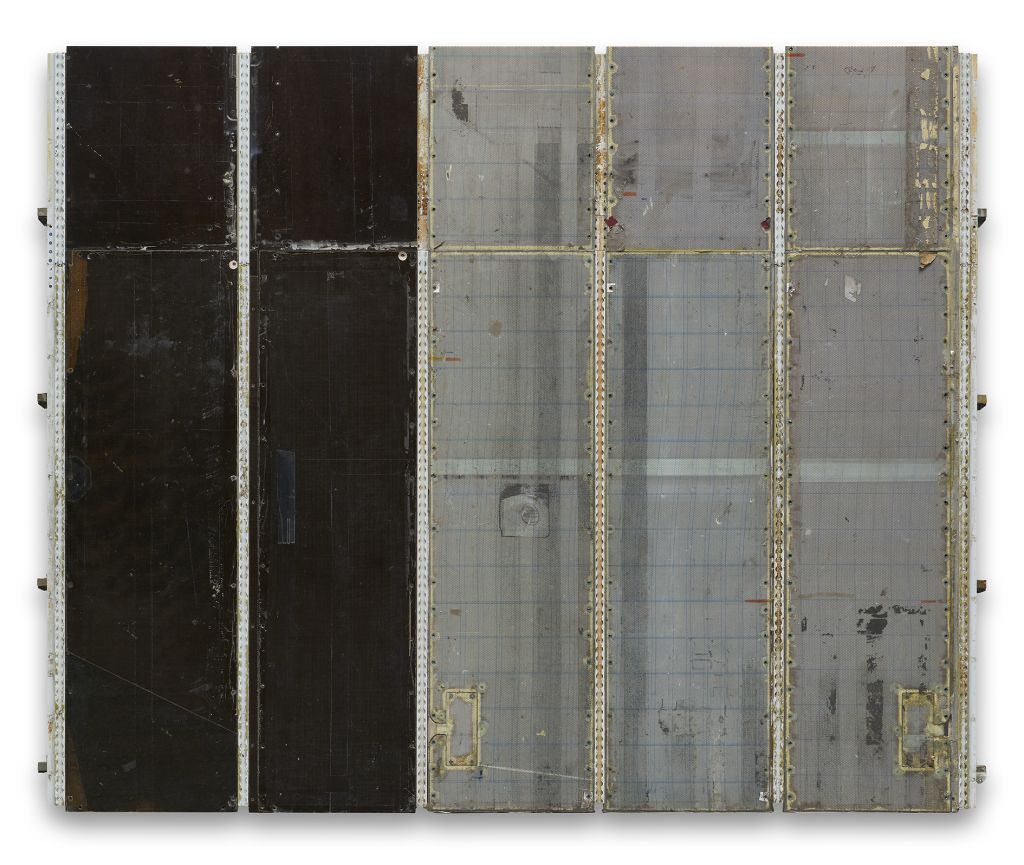

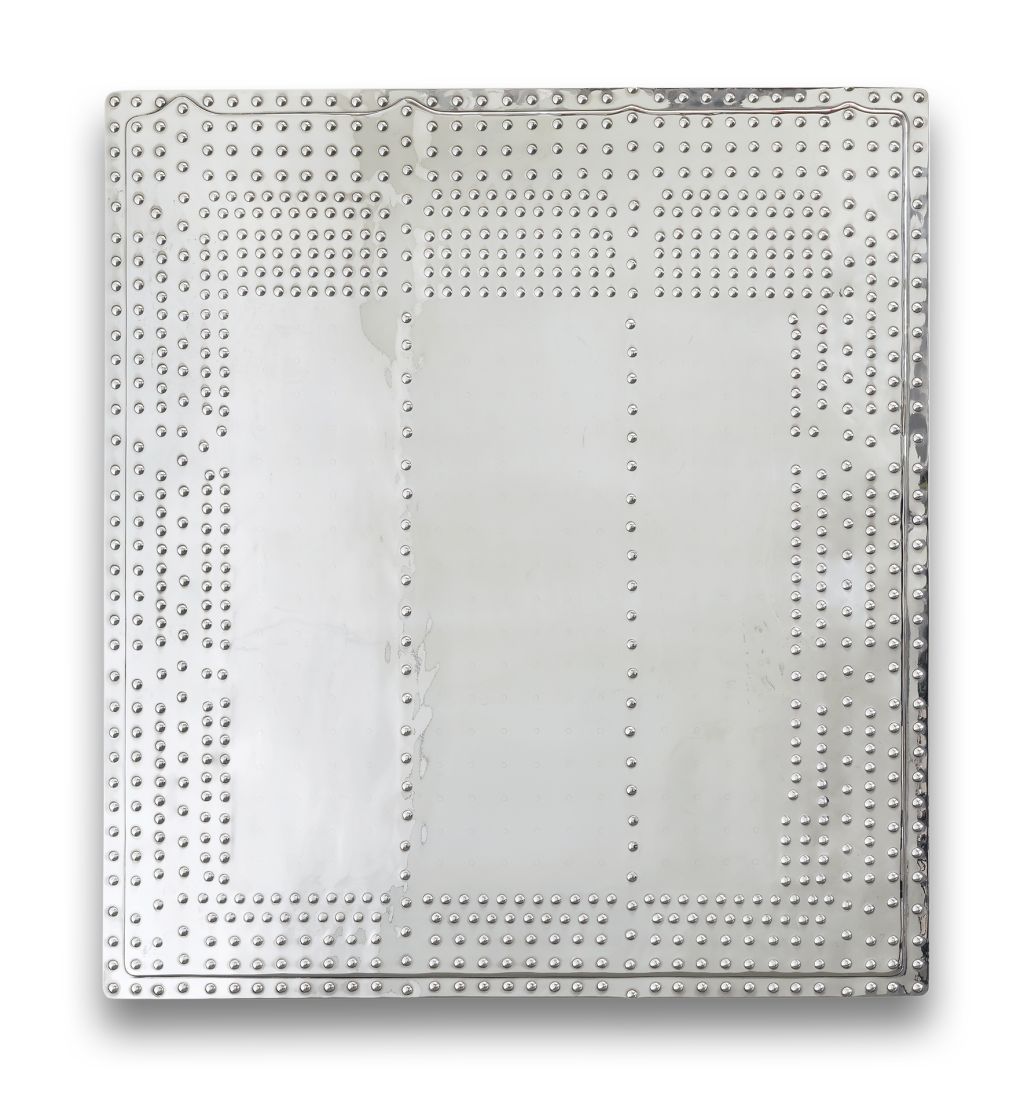

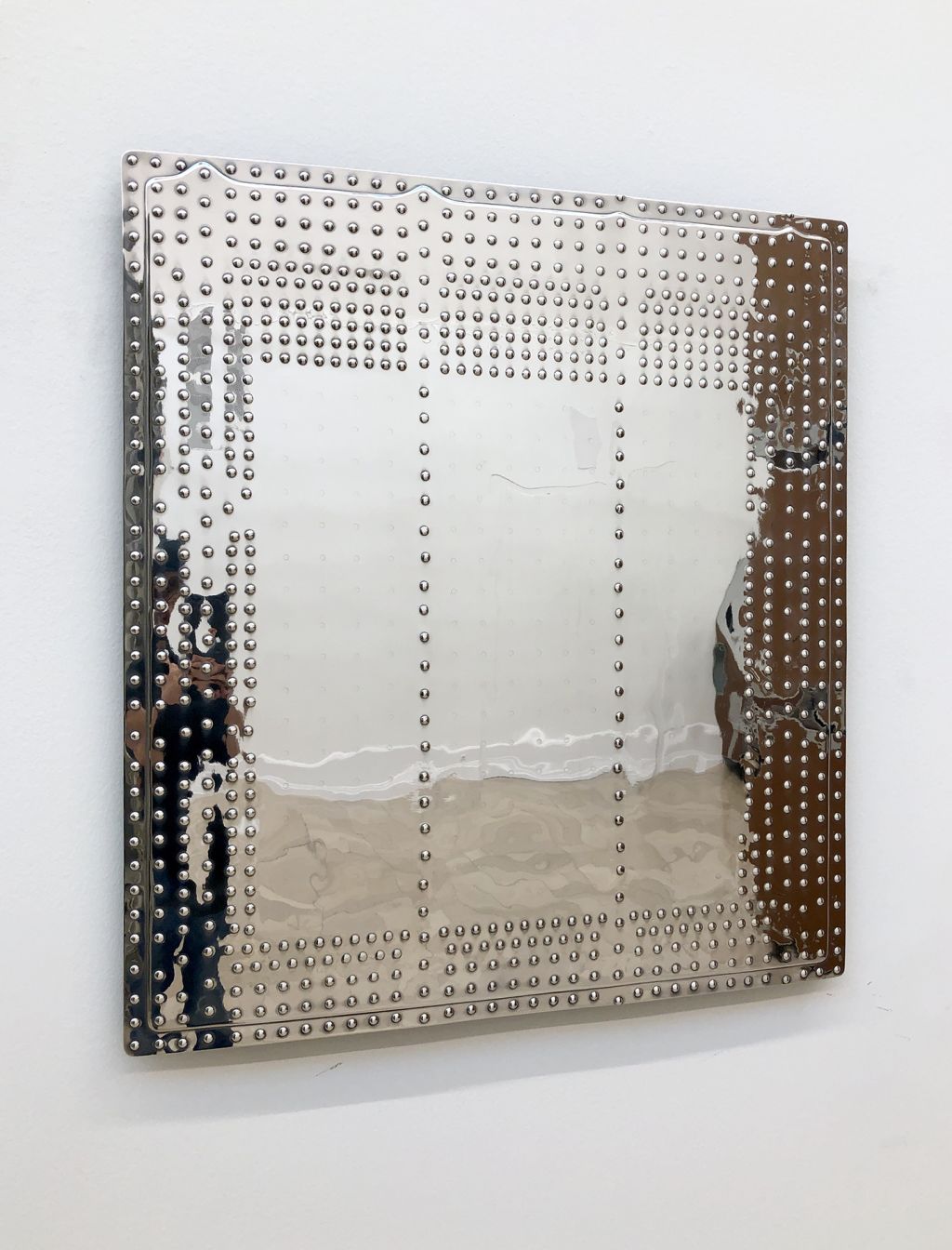

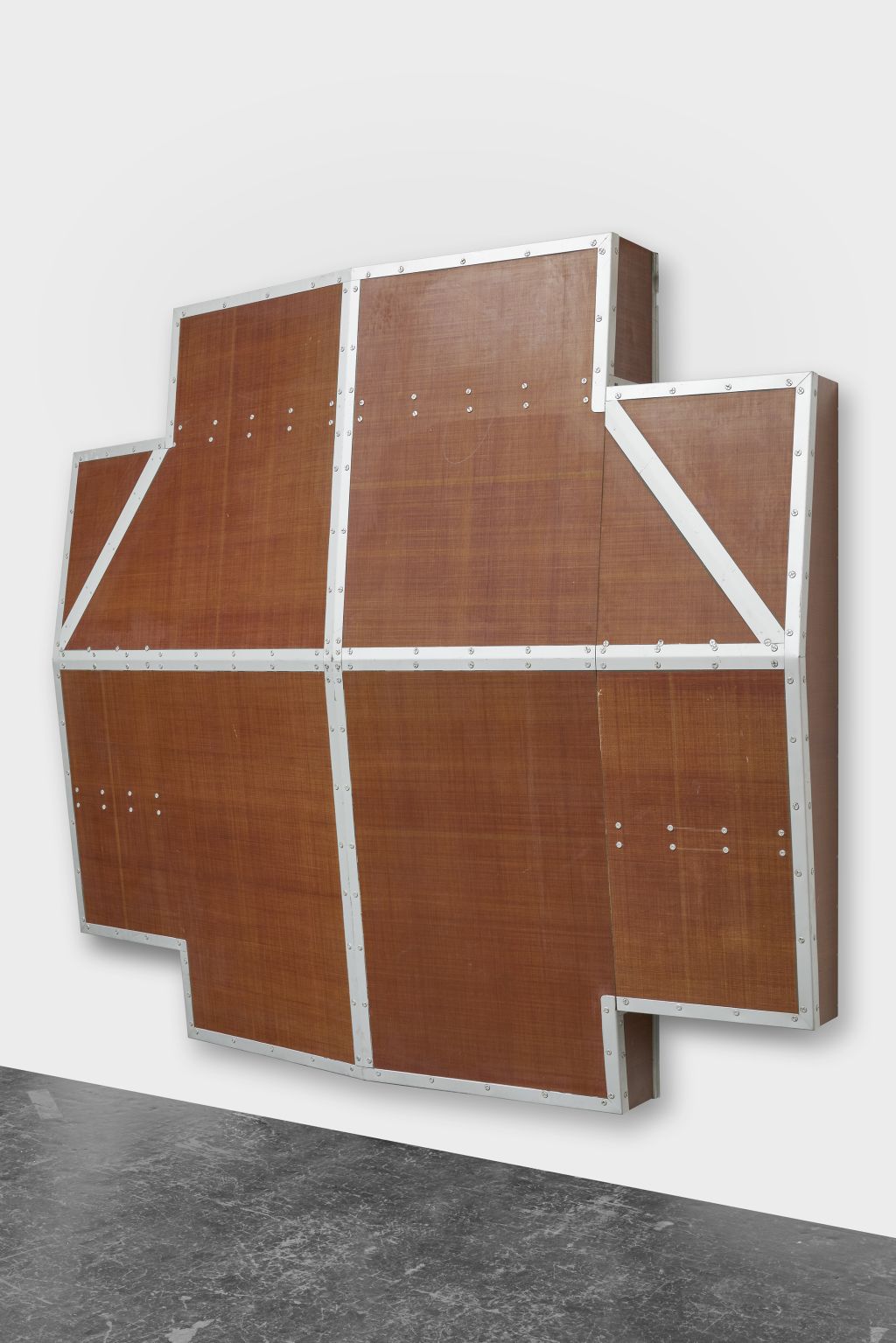

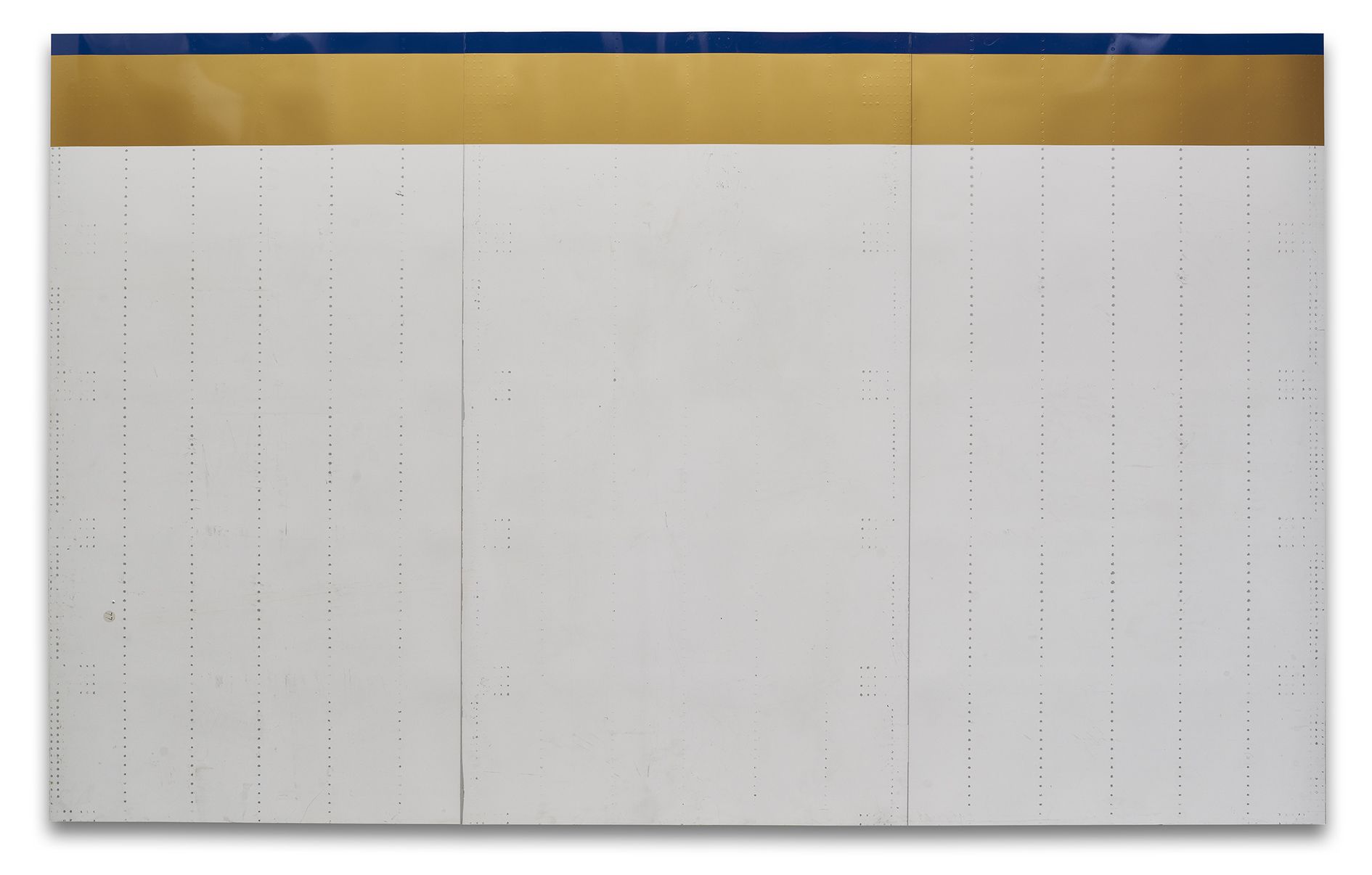

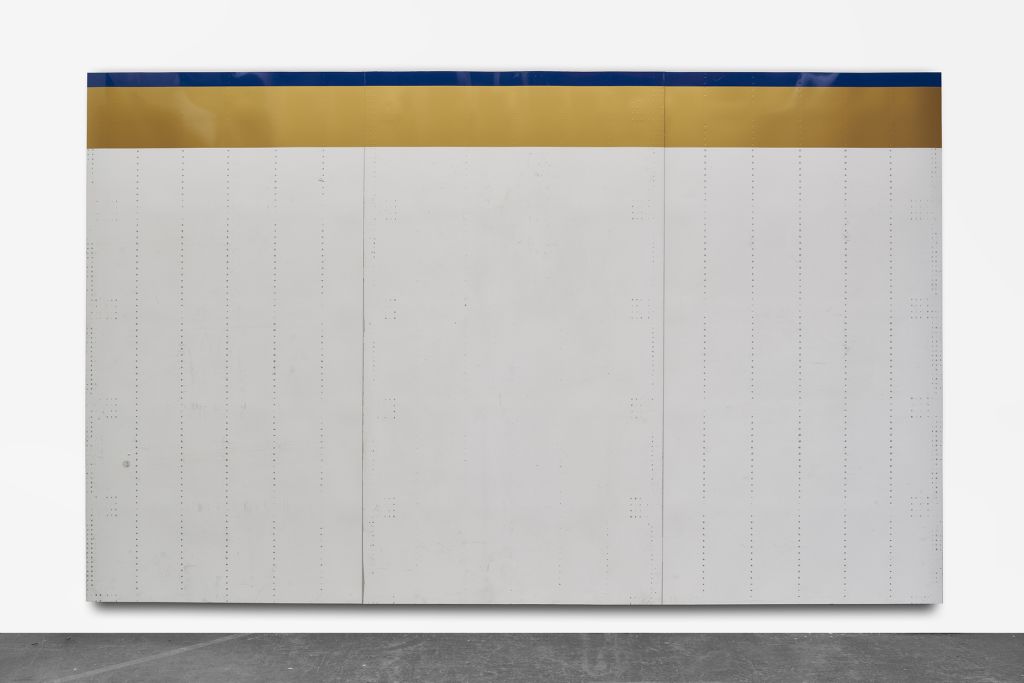

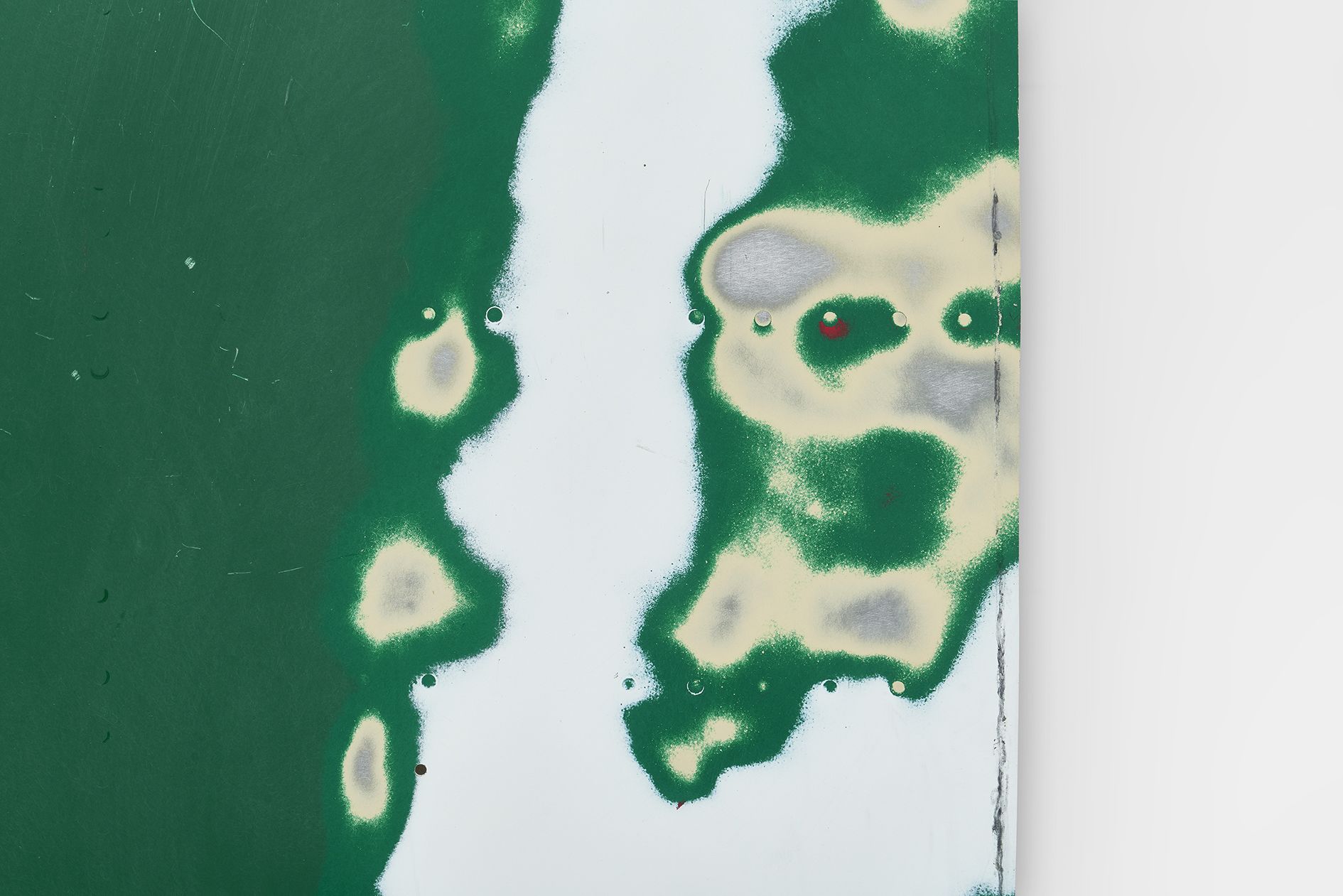

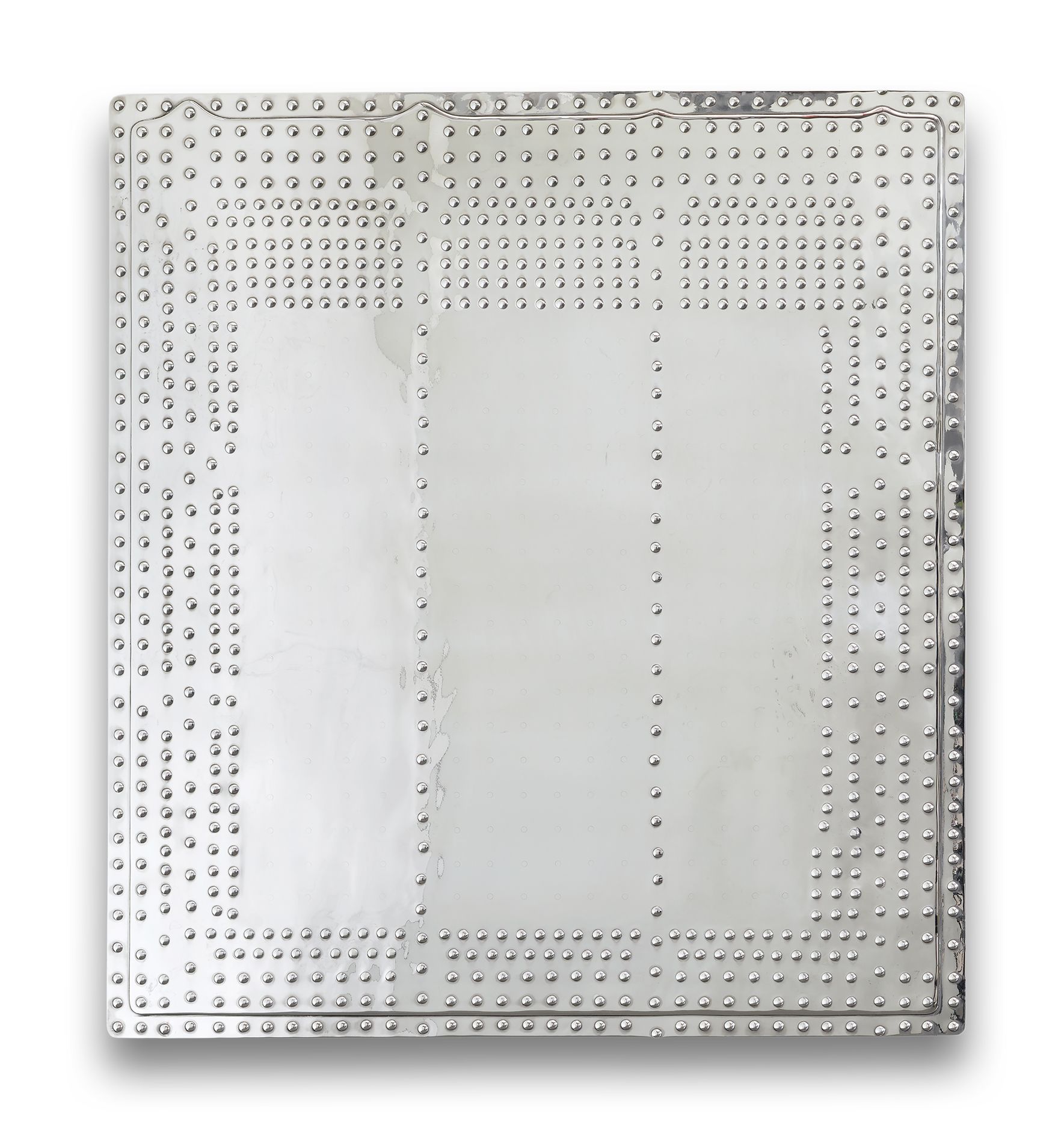

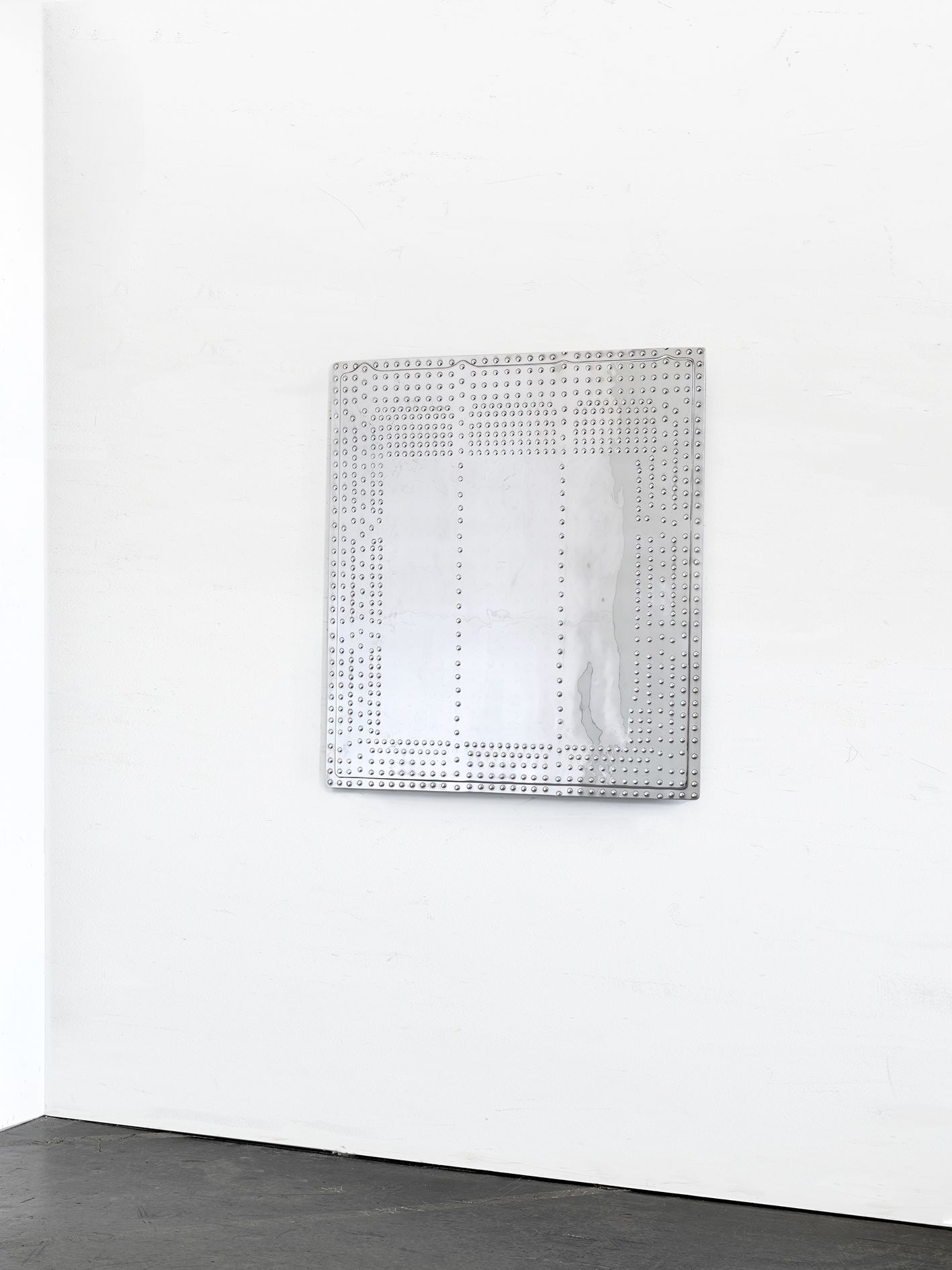

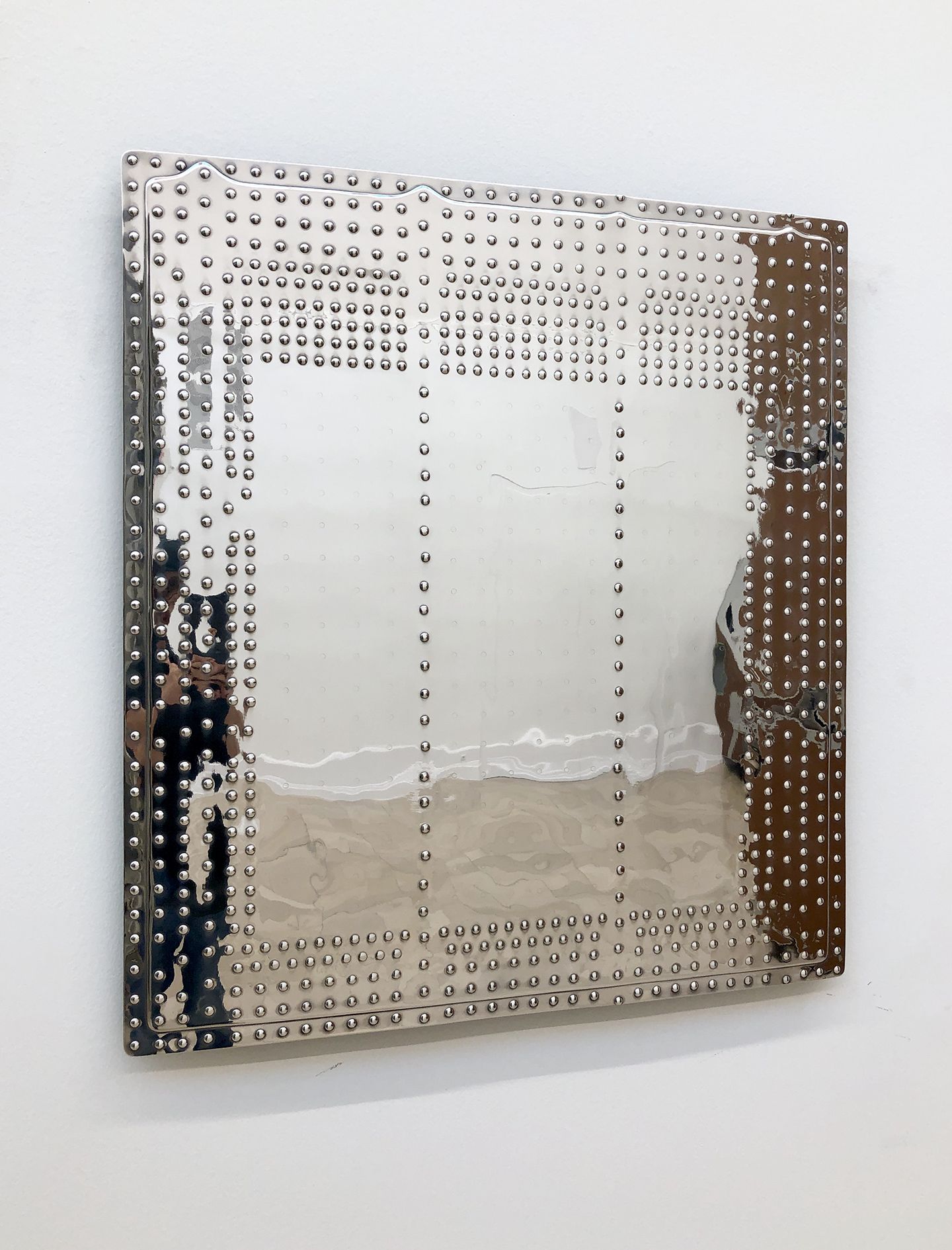

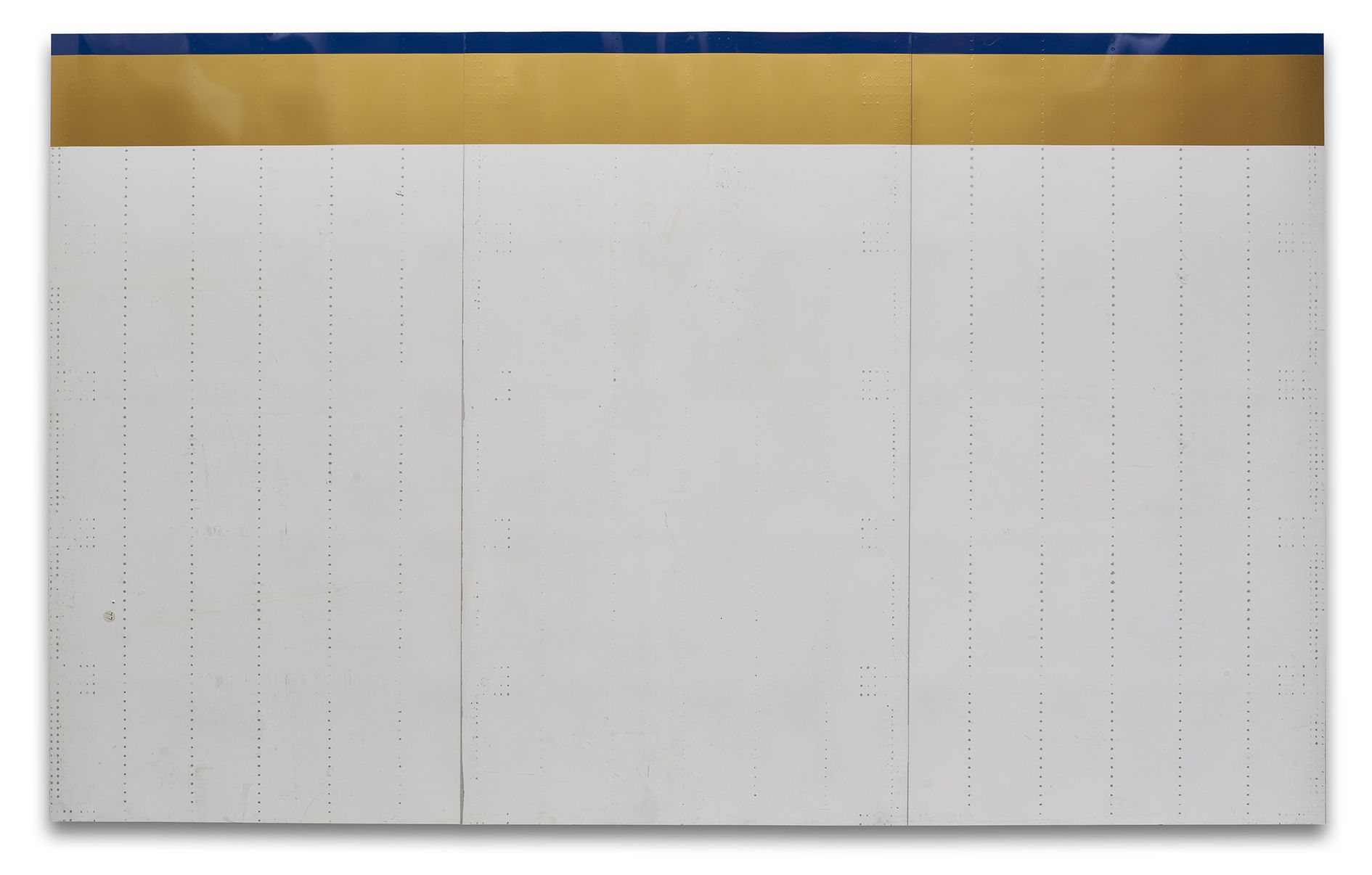

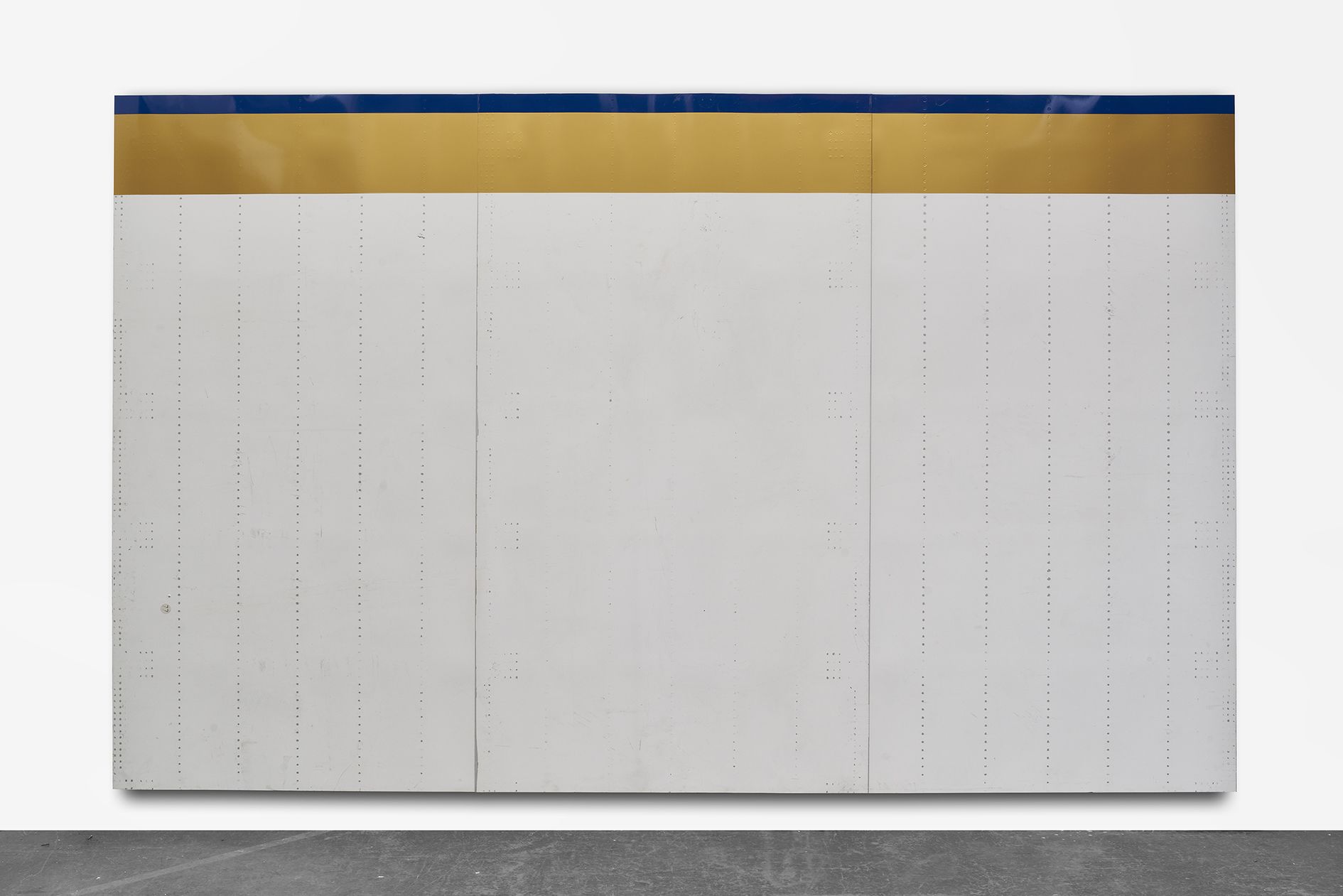

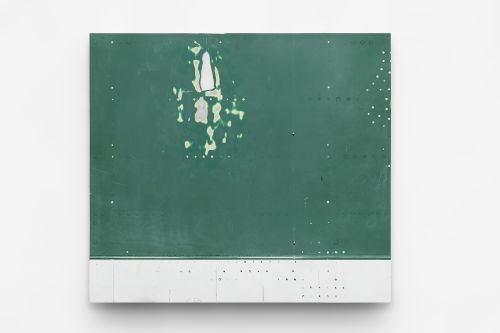

The work of Michail Pirgelis (*1976) updates the traditions of post-minimalism, the readymade and conceptual art while simultaneously resisting them. His process usually begins with found materials from aircraft cemeteries in California and Arizona, where disused passenger planes wait to be dismantled and recycled. The Cologne-based artist explores the limits of our understanding of objects, while radically expanding our experience of the sculptural.

© Sarah Lucas, 2024. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London and Contemporary Fine Art, Berlin. Photo: Jochen Littkemann

If not now, when?

Group Exhibition

Museum Beelden aan Zee, Den Haag

Through September 8, 2024

If not now, when? presents an international selection of over seventy sculptures and installations from the collection of art collector Max Vorst. The exhibition gives an impressive overview on the developments in contemporary sculpture in the twenty-first century and demonstrates the diversity, originality and high quality of one of the most important private art collections in The Netherlands, and it connects themes such as the contemporary image of the human form, abstraction, rhythm and construction while also showing the blurring of time.

Link