Irwin began his career as a painter in the 1950s. Though considered a defining figure of West Coast Abstract Expressionism, his focus was less on the actual painting than the charged realm of experience that came into play between painting and viewer. Irwin’s interest in the phenomenological experience of art soon led him away from the gestural language favored by his colleagues and toward a radically reduced visual vocabulary of color fields and stripes. A further step came in the 1960s when the artist dissolved conventional boundaries between painting and exhibition space by arranging disc-shaped paintings in such a way that they reflected various light sources. The resulting light installations became as integral to the work as the paintings themselves.

In the 1970s, Irwin abandoned painting and studio work altogether and developed a kind of installation art devoted entirely to the phenomenology of perception. His early interventions, made with modest materials such as scrim, twine, or adhesive tape, probed the aesthetic potential of exhibition spaces by dismantling familiar patterns of perception and directing viewers’ attention to environmental qualities that already existed in a given space.

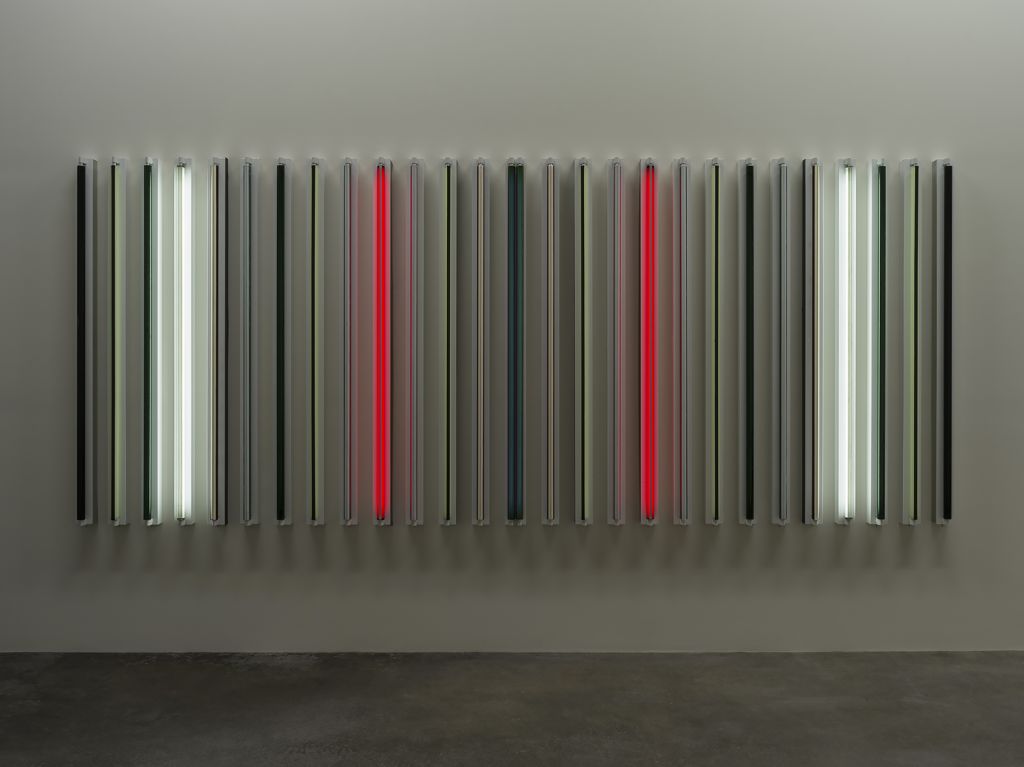

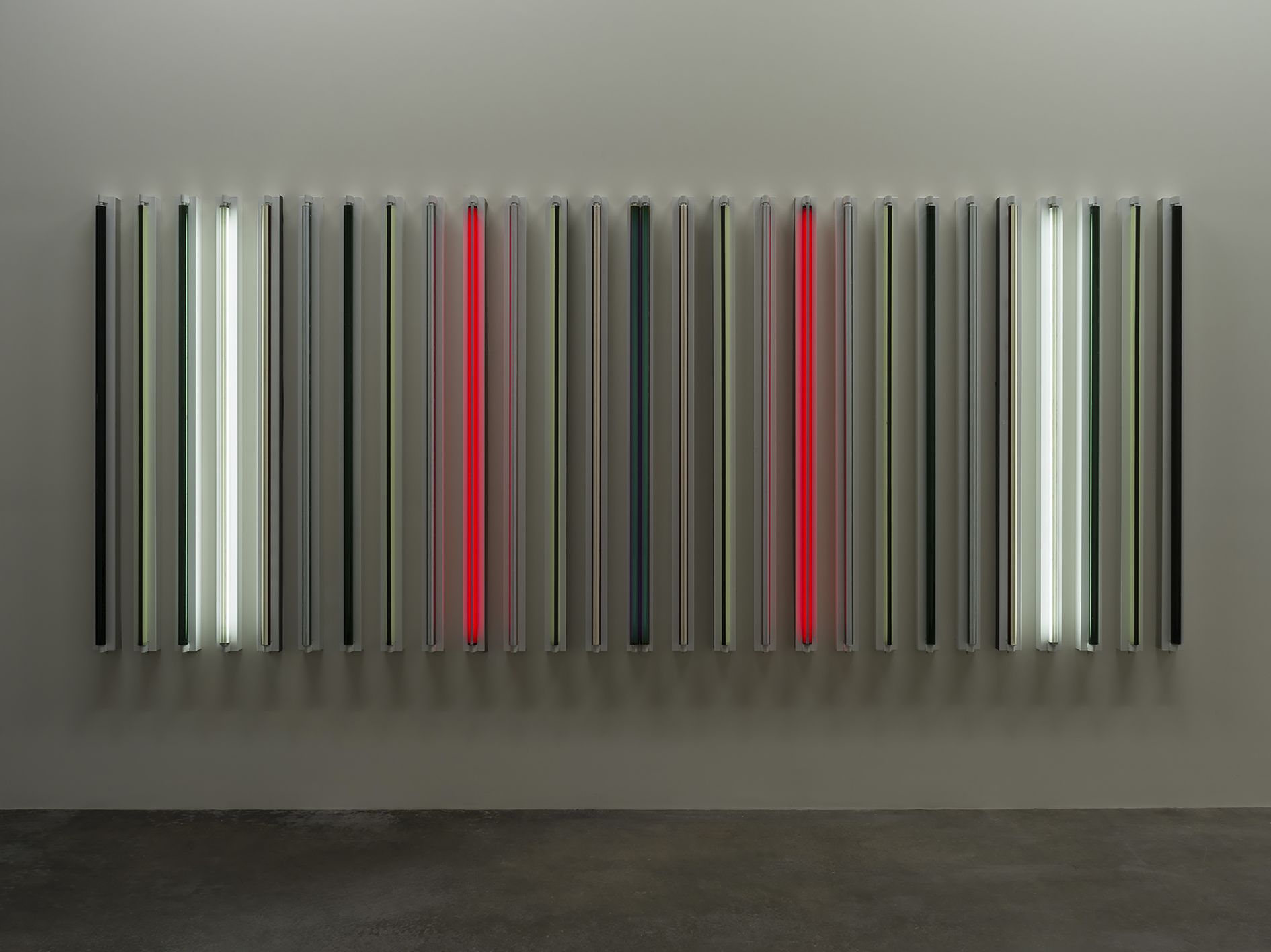

From that basis, the artist radicalized his philosophy of aesthetic experience (ideas also reflected in Irwin’s many theoretical essays and lectures) and built a practice that consistently conceived of art as a response to the perceptual conditions of a specific site, whether spatial, cultural, historical, or institutional. The resulting works engage with the particular shape of an exhibition space in a museum, a quality of light in the treetops of a park, a city view from a window, or waves breaking over the Pacific Ocean. Some of Irwin’s interventions are of an almost inconspicuous, architectural nature. Others consist of installations employing materials such as fluorescent light tubes, semi-transparent Plexiglas walls, wire-and-steel constructions, or colored aluminum panels. Some involve designing entire gardens. His work subverts the dominant logics of space and architecture by recalibrating the viewer’s physical and sensual experience, altering public space, and creating surprising patterns of movement. Works in this vein include his legendary Central Garden (1997) at the Getty Center in Los Angeles; his installation Excursus: Homage to the Square³ (1998) at the Dia Art Foundation in New York (reimagined at Dia:Beacon in 2015); or untitled (dawn to dusk) (2016), his expansive architectural intervention on the grounds of the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

Irwin’s conditional art could also be understood as an ethical project, which he expanded in diverse philosophical writings that posited art as a form of pure inquiry and rooted his approach within the discourse of modern and contemporary art. His works manage to interact with their surroundings without imposing their beliefs on anything or creating new social hierarchies. They set the stage for a radical pluralism of thought and experience, offering the viewer an entirely new way of seeing and perceiving.