Trecartin studied Film, Animation and Video at RISD at a time of immense change in access and ability in moving images. With his undergraduate thesis film, A Family Finds Entertainment (2004), Trecartin established himself as one of the foremost innovators of the medium, encapsulating the ever-evolving relationship between humans as mediated by social groups, technology, and self-expression.

The primary mode of Trecartin’s practice is, arguably, language. In his tightly scripted films, the artist often examines the social and cultural weight of words and dialogue, expressed in forms both anarchic and totalitarian. Verbal shibboleths abound, marking characters as in or out of various taxonomic groups, and with many characters ultimately either subsuming themselves into a larger social whole or carving out new linguistic areas of self-definition. In movies such as K-CoreaINC.K (section a) (2009) and CENTER JENNY (2013), language is used as a source of conformity: characters are drilled in corporate or pedagogical verbiage, with stock phrases and jargon repeated over and over again. But even within the strict societal rules of Trecartin’s videoscapes, the glimmers of differentiation win out.

What strikes one most upon first viewing Trecartin’s movies is the synesthetic quality of the artist’s editing. The gestures of the camera are highlighted through the use of foley and sound design to create the sense of a living and breathing apparatus, a character or force in its own right. The editing speaks, talking back to the characters, manipulating situations, and changing outcomes. The editing acts as a double to the language of the narrative, establishing an intricate vernacular of movement and sound.

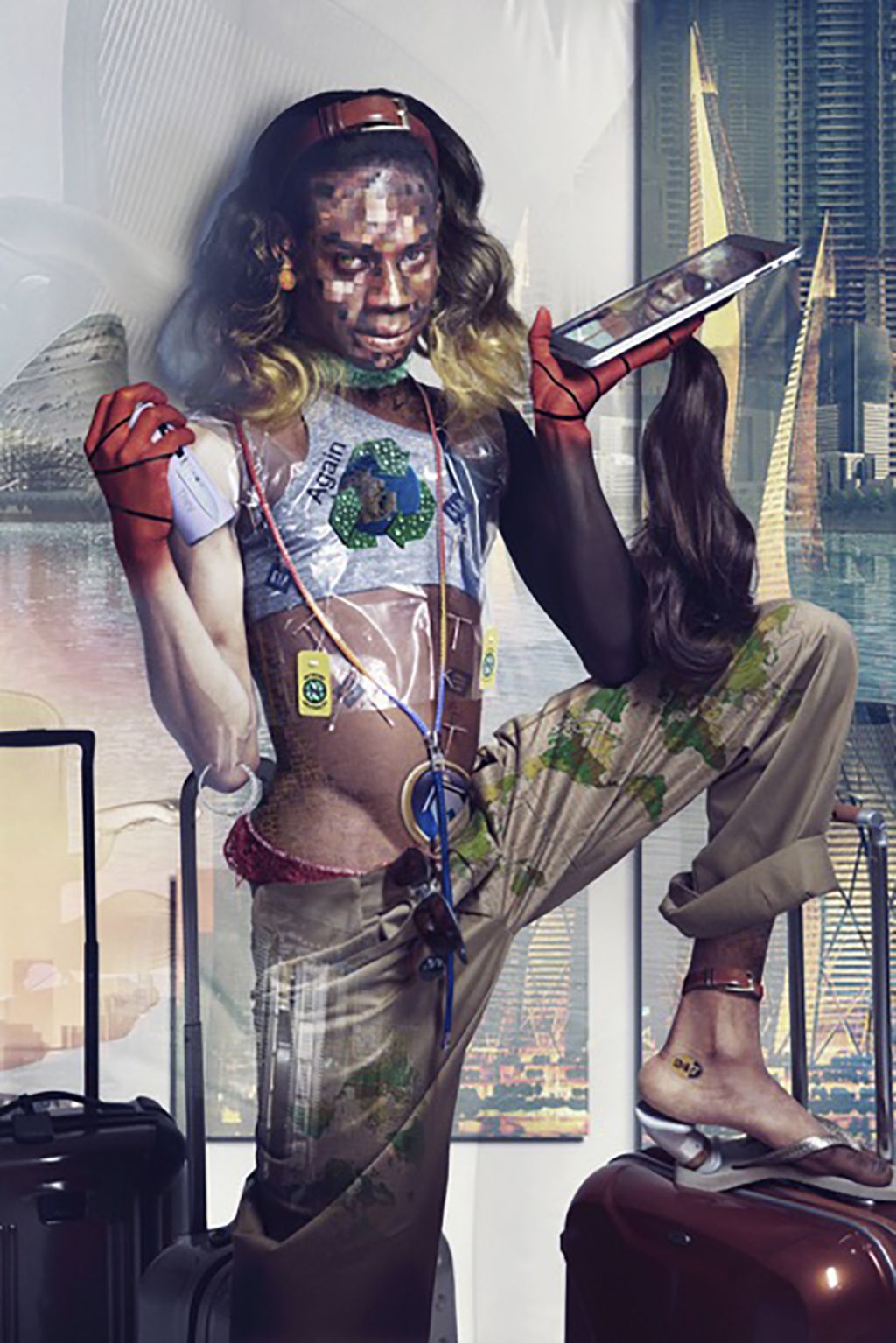

Trecartin’s films are populated by a singular crew of characters, many of them played by Trecartin himself. Through the use of wigs, outfits, and face paint, they transgress boundaries of gender, sexuality, and self constantly. This freedom allows each role to examine more distinct concepts of characterization. When gender, sex, and other forms of identity are as easy to take on and off as costumes, definitions of selfhood become simultaneously fraught and ecstatic. An eagerness to define and disrupt permeates the screen.

Trecartin focuses intently on collaboration. The films are shot on meticulously crafted mise en scène which function as both film sets and creative platforms for the artist’s varied collaborators. Most prominently among these is Trecartin’s frequent artistic partner Lizzie Fitch. Their work together has evolved into the creation of “sculptural theaters” for many of the works, environments in which the physicality of the movies is extrapolated to an even further degree.

Part of the high school class of 2000, Trecartin’s practice has deftly mirrored the societal shifts of his own millennial generation. In Junior War (2013) we find a teenaged Trecartin behind the camera, capturing his high school peers’ initial hesitancy of being filmed develop into a preening performance of youth. While works of the late aughts such as Trill-ogy Comp (2009) find the warring intersection between the wonder of new forms of entertainment, such as reality TV, and the bleak corporate reality during The Great Recession, later works such as Temple Time (2016) and Whether Line (2019–ongoing) interrogate narratives of self-preservation through class identification, ownership, and the concept of “settling down.” Though often hyper-specific, these thematic arcs fit vitally into contemporary histories, providing a radically queer lens through which to examine American societal evolution within the 21st century.