Sources cited:

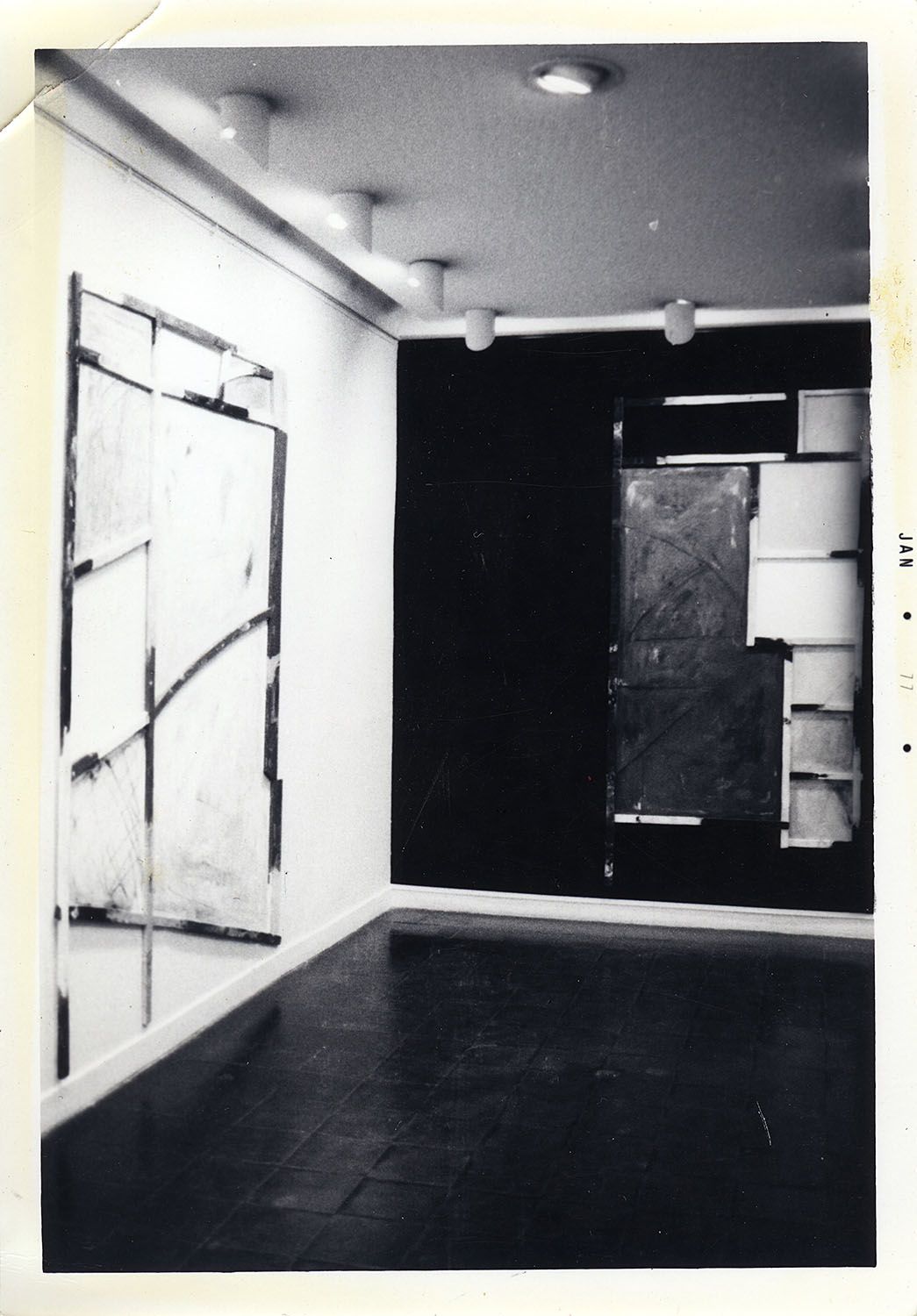

1. University of California, Los Angeles, Wight Art Gallery, Los Angeles, Transparency, Reflection, Light, Space: Four Artists, January 10–February 14, 1971 (exhibition catalogue).

2. Spark, Clare. Interview of Craig Kauffman – Co-Founder of the Peripatetic Artists Guild. KPFK: Los Angeles, broadcast February 8, 1971. In the transcription of interview, Kauffman states: “The piece at UCLA consists of water reflections on the wall. And, of course, the water in these plastic troughs on the floor and the mirrors, and these lights that frame the thing, and also the fans, which set up a kind of rhythm on the wall of the reflections.

3. According to his archives and journals Kauffman worked in three studios, 150 La Brea, Laguna Beach, 20E 17th St., New York, and Cité Internationale des Arts, 18 Rue de l’Hôtel de Ville, Paris, France

4. Frank Gehry, speaking at Kauffman memorial, Museum of Contemporary Art, July 21, 2010

5. Auping, Michael, Los Angeles Art Community: Group Portrait. Craig Kauffman Interviewed by Michael Auping. Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, 1976–1977.

6. Galerie Darthea Speyer, Paris, France, Craig Kauffman, March 6–April 6, 1973.Kauffman exhibited 7 of the 1972-3 works.

7. Auping, Michael, UCLA interview 1976, p. 56

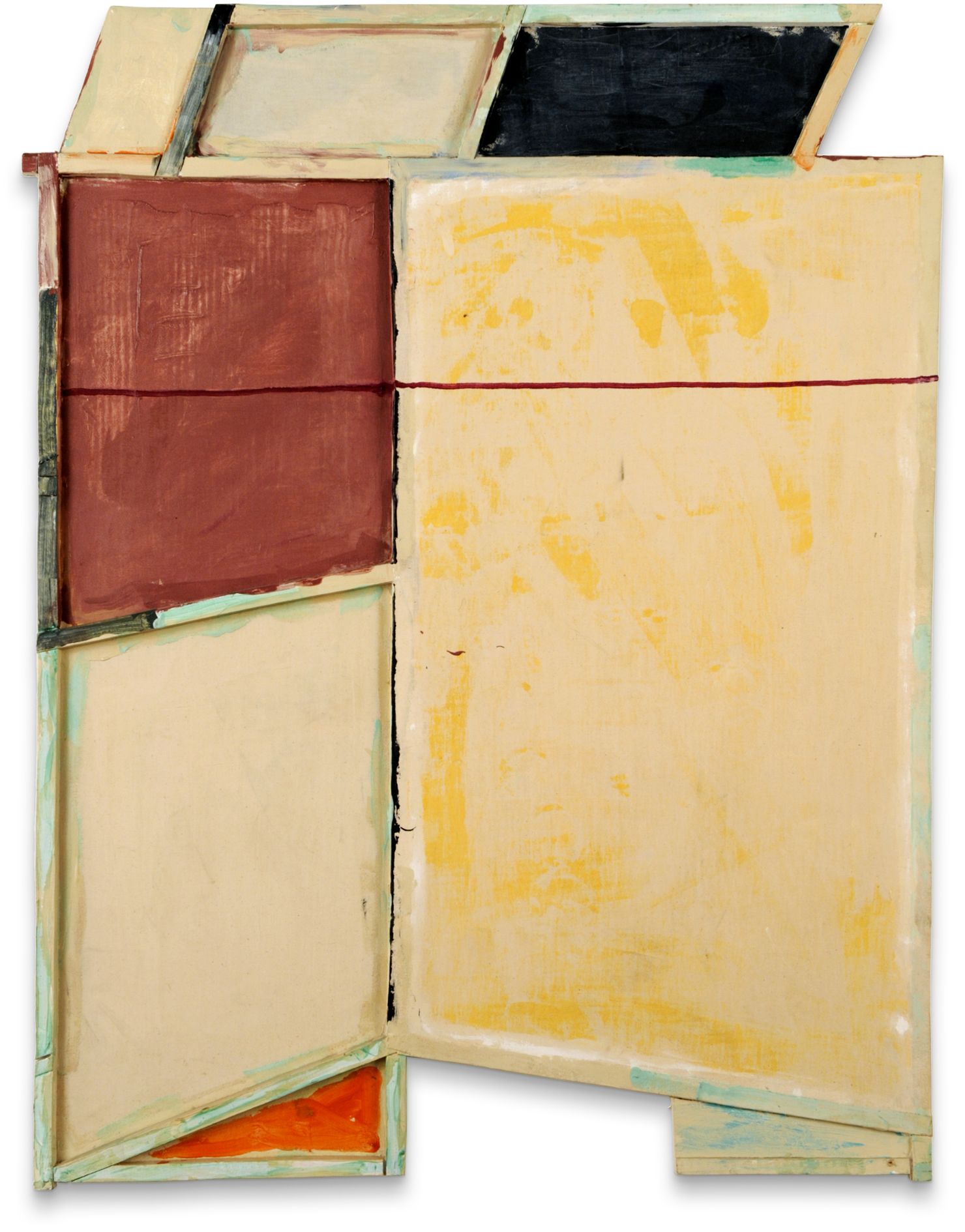

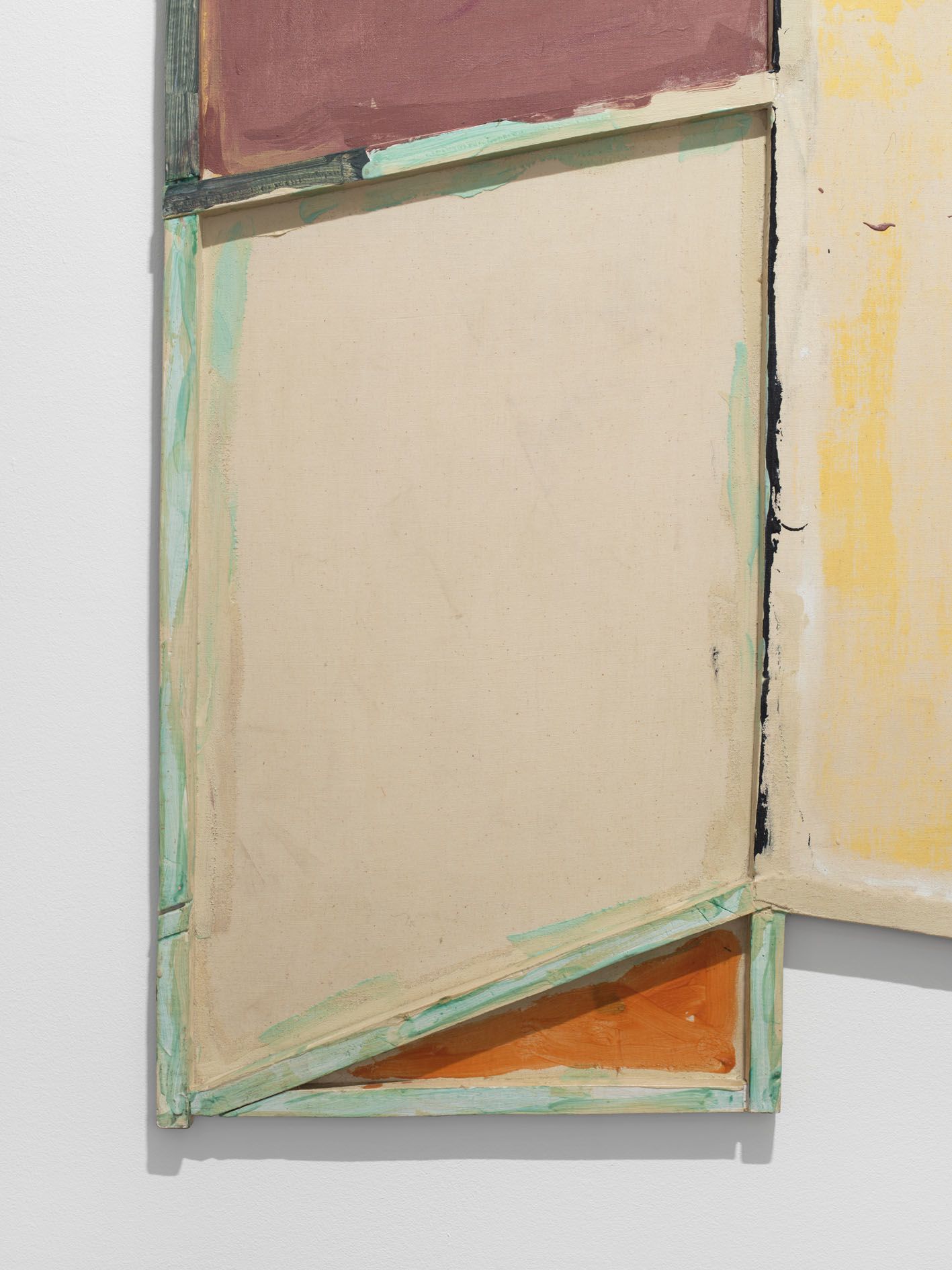

8. Shi Tzu, 1973–74 Acrylic on Styrofoam and muslin, 97 x 88 ½ inches.

9. Wilson, William. “A Heartfelt Showing of Kauffman.” Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1981, p. 81.

10. Auping, Michael, Los Angeles Art Community: Group Portrait. Craig Kauffman Interviewed by Michael Auping. Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, 1976–1977.