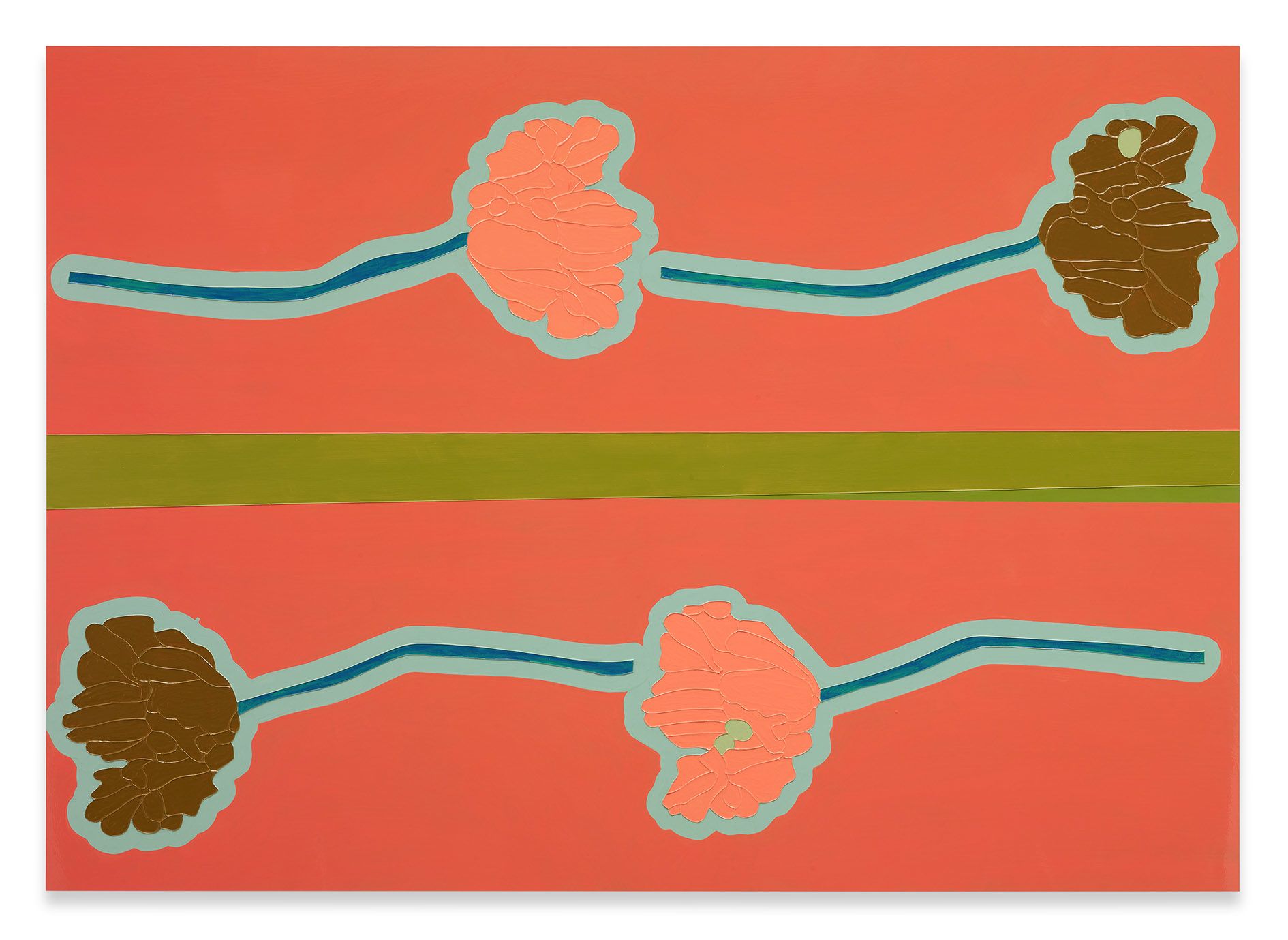

While discussing the painting Two Flowers, Hume mentions the fundamental importance of “how things meet” in both painting and “all of life.” On one level, then, this is a formal concern for the artist: How do shapes and colors interact, how do balance, symmetry and repetition contribute to the overall effect of the painting? On another level, “how things meet” is about dialogue and intimacy. Painting itself, and the emotion and energy that it conveys, becomes a metaphor for the connections we make between ourselves and others.

The Mannerist Bronzino is a longtime favorite of Hume’s, and you can see how he would admire his clear and delineated forms. Yet the artists also share a deep sensuality, and a capacity to conjure intimate connections between the figures they portray. The Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint, in London’s National Gallery, depicts Mary and the Christ child suspended forever in a moment just before their faces touch.

Hume invokes a similar mood of intimacy in each of the three paintings featured in Double Bloom. In The River, the flowers are at once separated by the strong bar of the horizon, yet the interlinked blooms reflect each other, and reflect upon each other. The vertical energy of Two Flowers creates a tender connection between the blooms, as if they were lovers’ heads on a bed. Two Blooms, Grey Fields conveys a rich emotional life. There is at once a melancholy in the ragged space between the two flowers, as well as a powerful sense of longing and affection. As with Bronzino’s mother and child, the flowers are suspended forever, loving yet hesitant, on the verge of an intimate connection.