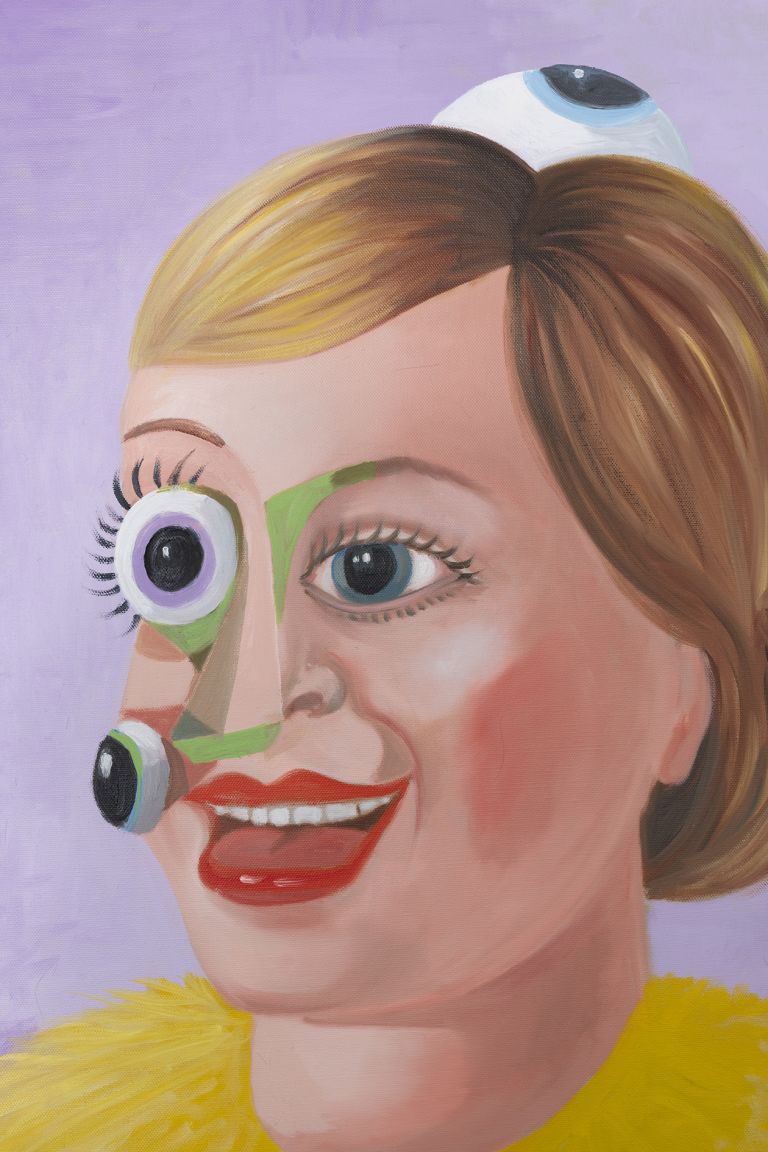

From his earliest paintings, the human eye has been at the heart of George Condo’s oeuvre. The Self Creator (1984) features a disembodied eye in a landscape, alongside a classical column, a clock, a globe, and an arm, itself pinched by an almighty black hand reaching down from the sky. The egg-like eye, always open, takes its place among cultural monuments, itself a source of revelations. The Eye of the Brain (Polyphemus) (1990) features a single eye atop an elongated neck, as if seeing were the purpose of its existence. One of the artist’s largest canvases, Visions of St. Lucy (1992–93) features the saint, whose eyes were plucked out, amid a landscape populated with disembodied eyes. From his earliest works to the present day, Condo has turned to the eye for inspiration: not only the delicate organ we use to see the world around us, and thus the outlet of the painter’s creative energies, but also a seductive form to paint.