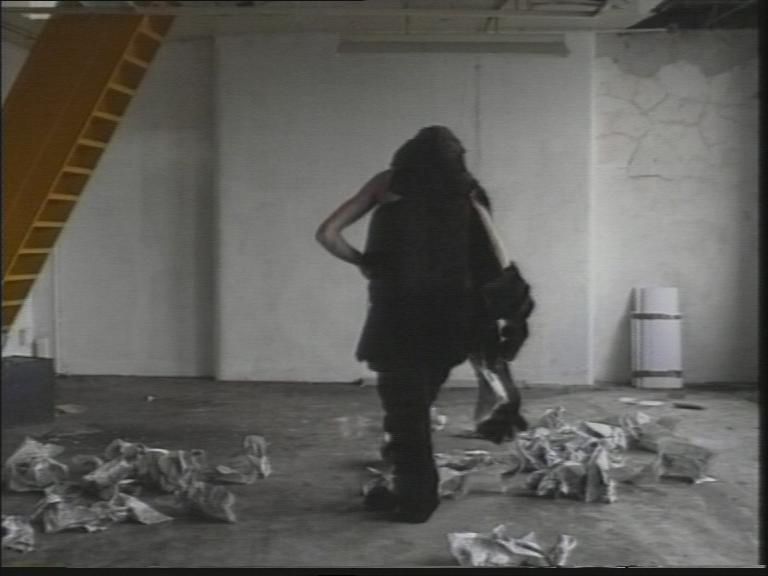

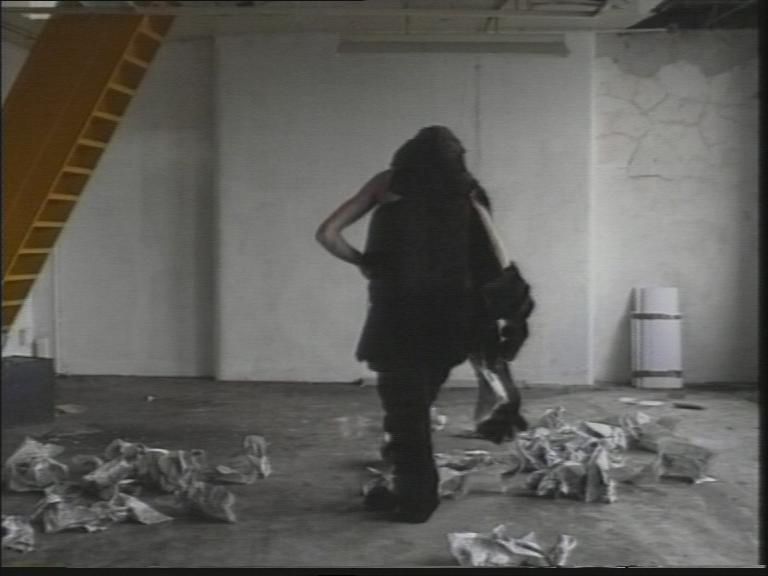

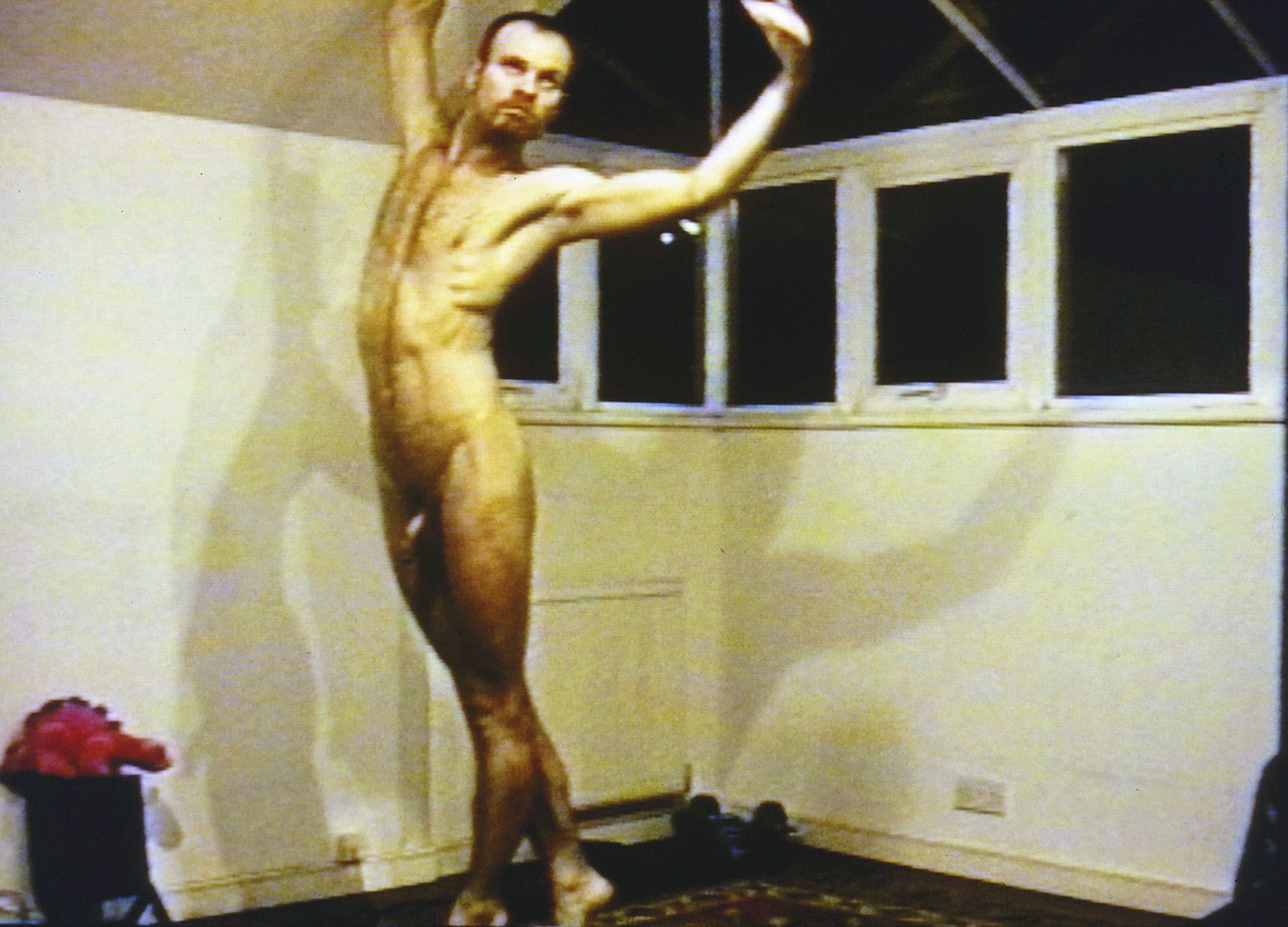

The home-movie quality of Fairhurst’s video and its determined DIY aesthetic is a significant feature of its visual language, equally apparent in the other works; Hume sat clothed in an overfilled bath in an industrial yard wearing a Burger King crown; Fairhurst and Hirst in full clown regalia discussing life and death in the pub; Taylor-Johnson presenting a naked figure slowed down and ecstatically raving to the strains of what we hear as a richly romantic piece of music; and in the basement gallery, Gillian Wearing silently dancing in a busy shopping centre. The themes of solitary dancing and Beckett-like, existential absurdism are at times indebted to a lineage of British surreal comedy yet imbued with psycho-drama that conveys a desire to break out, break away and declare a new freedom, literally jumping and flailing to declare a Year Zero. In the lineage of punk they make use of friends, cheap technology and seemingly non-descript space to become themselves.

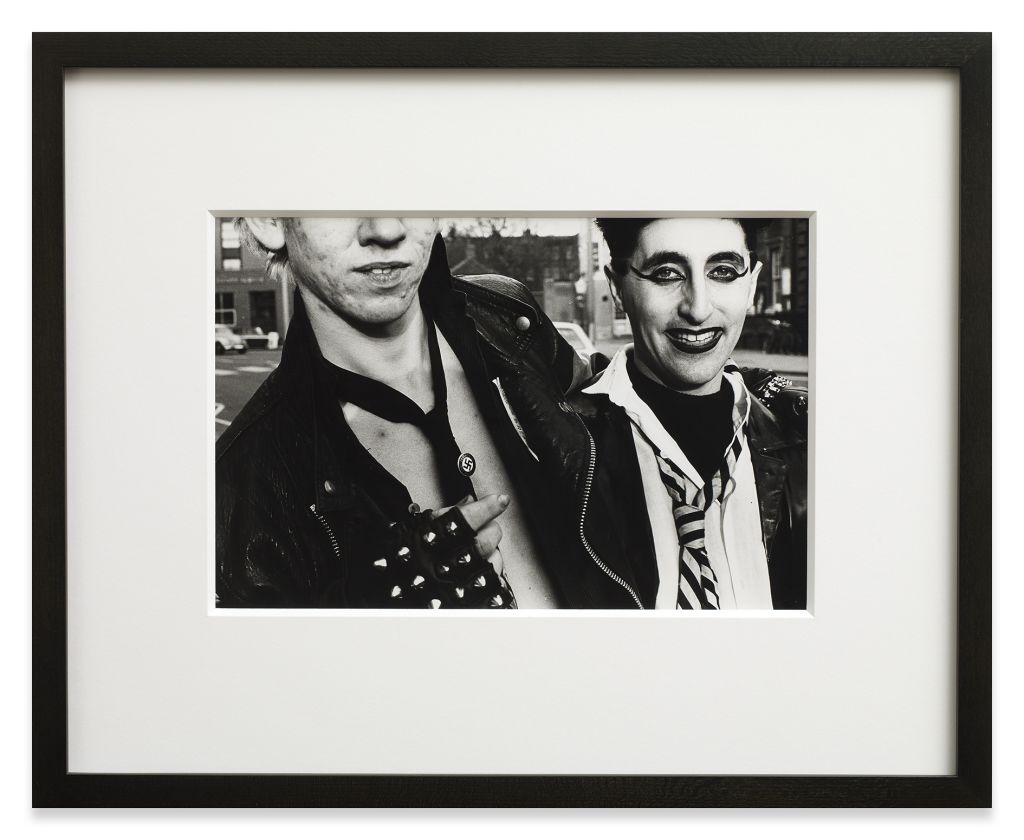

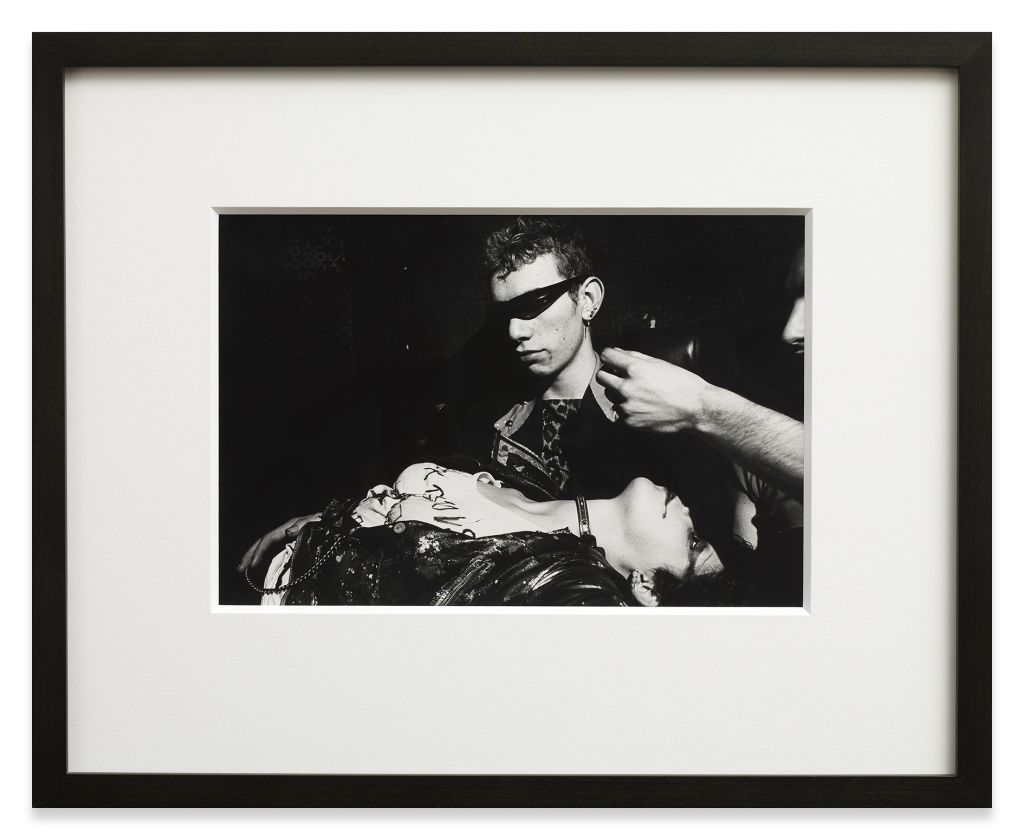

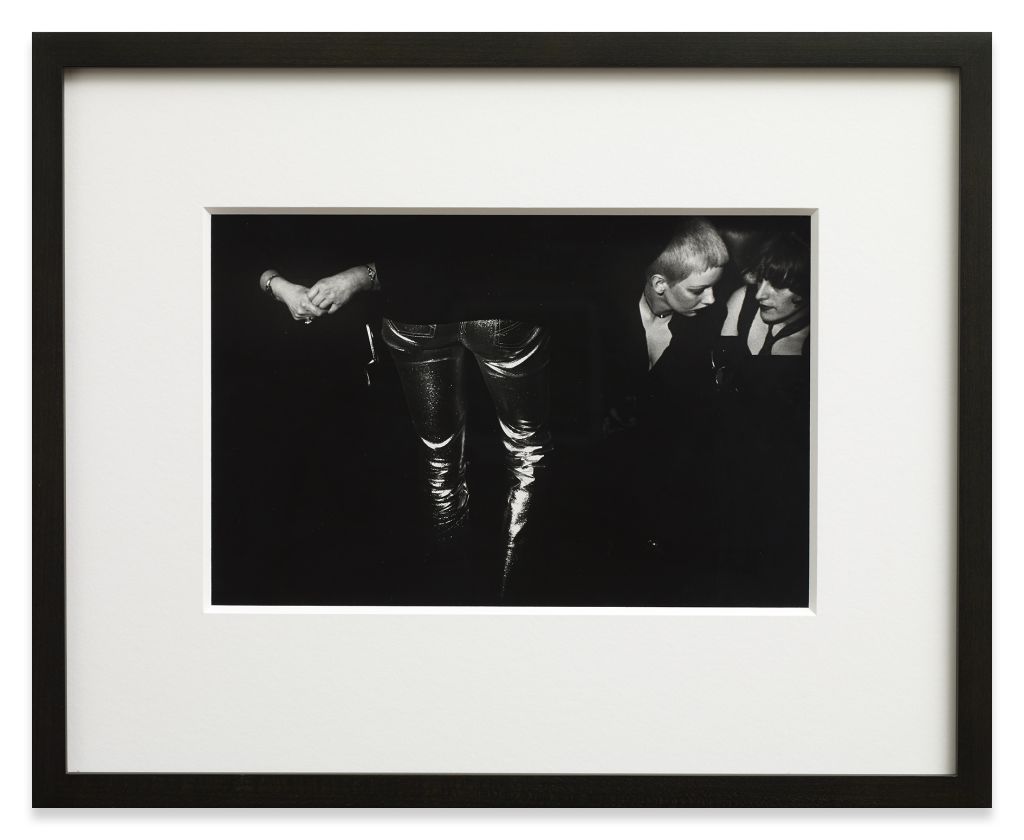

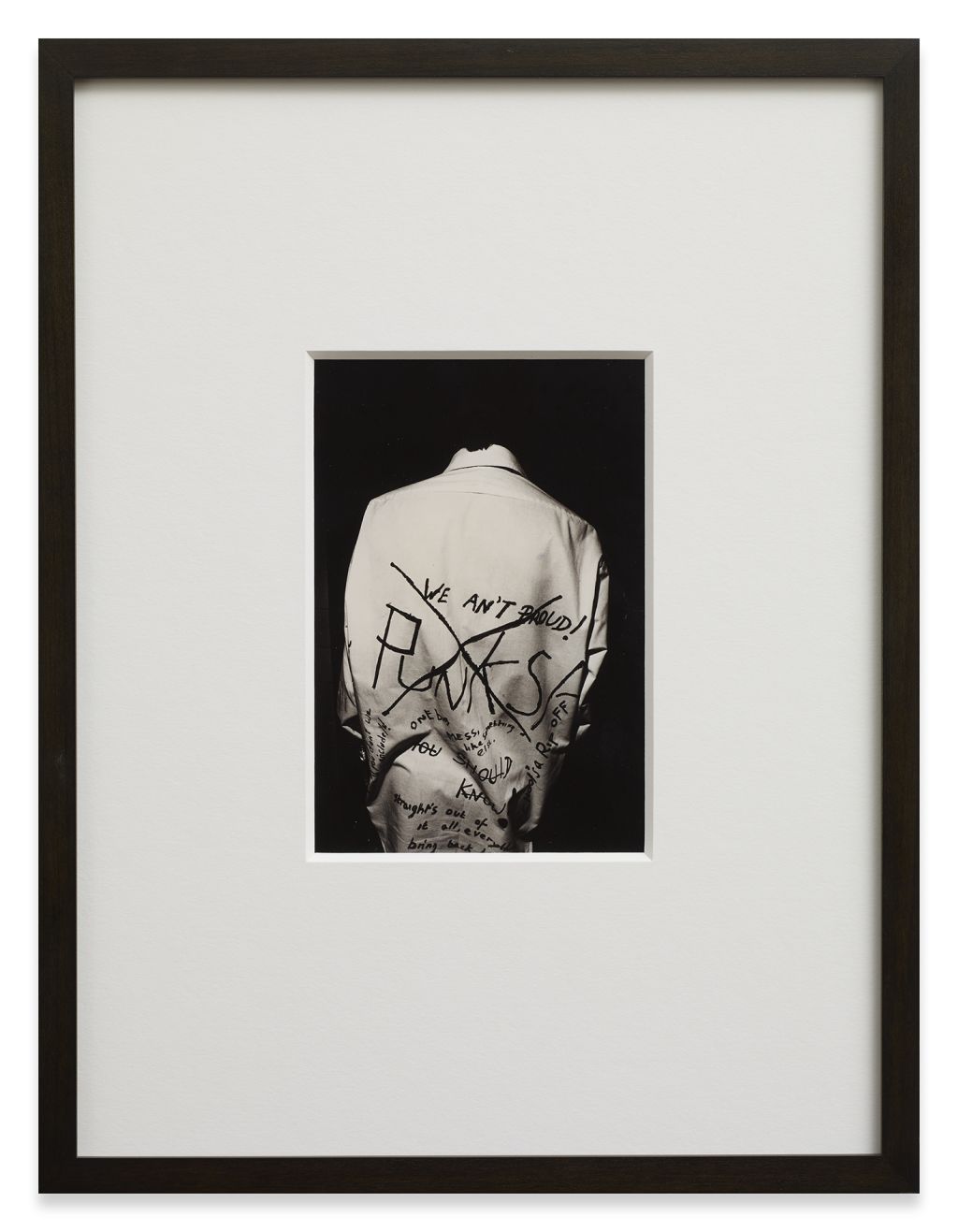

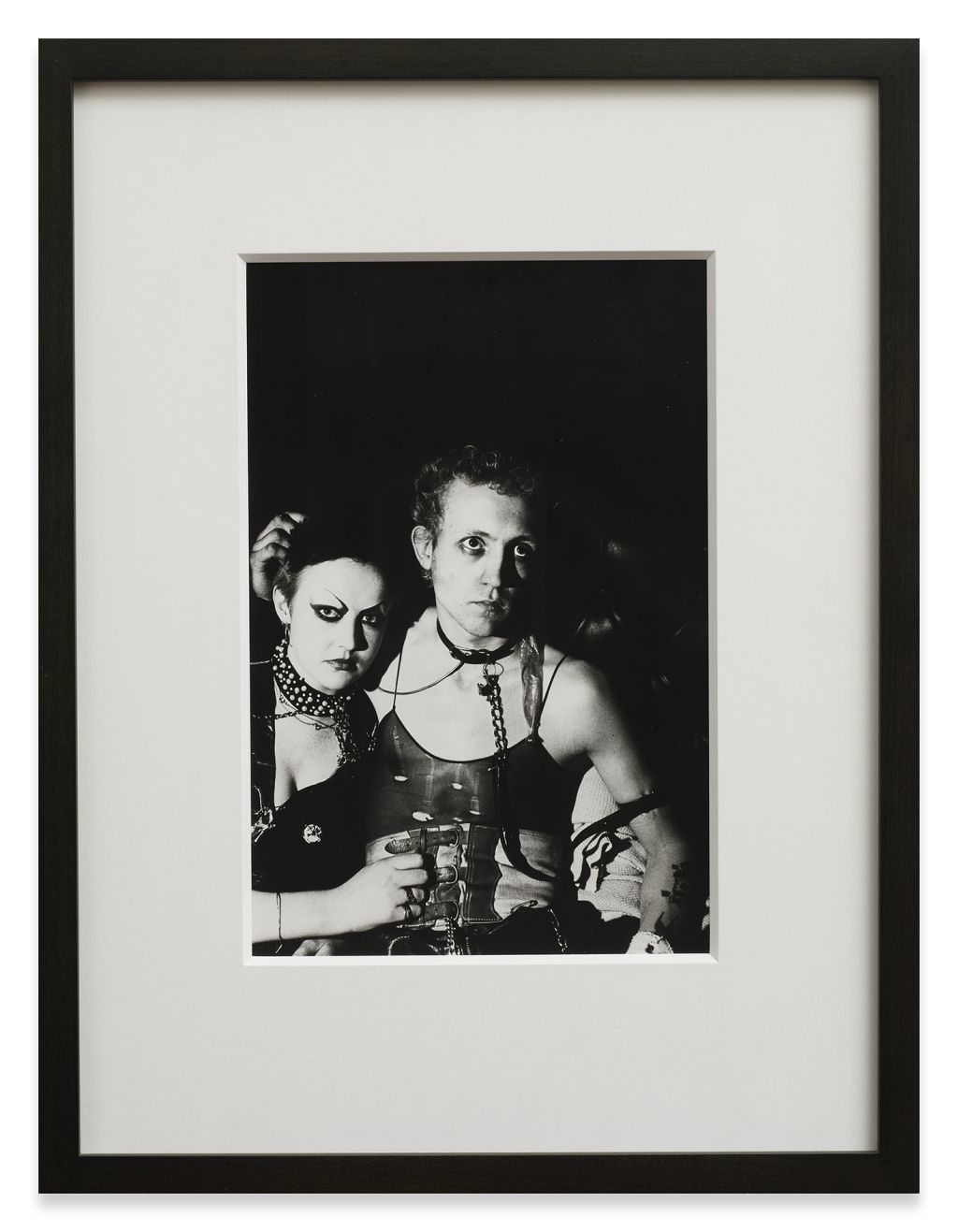

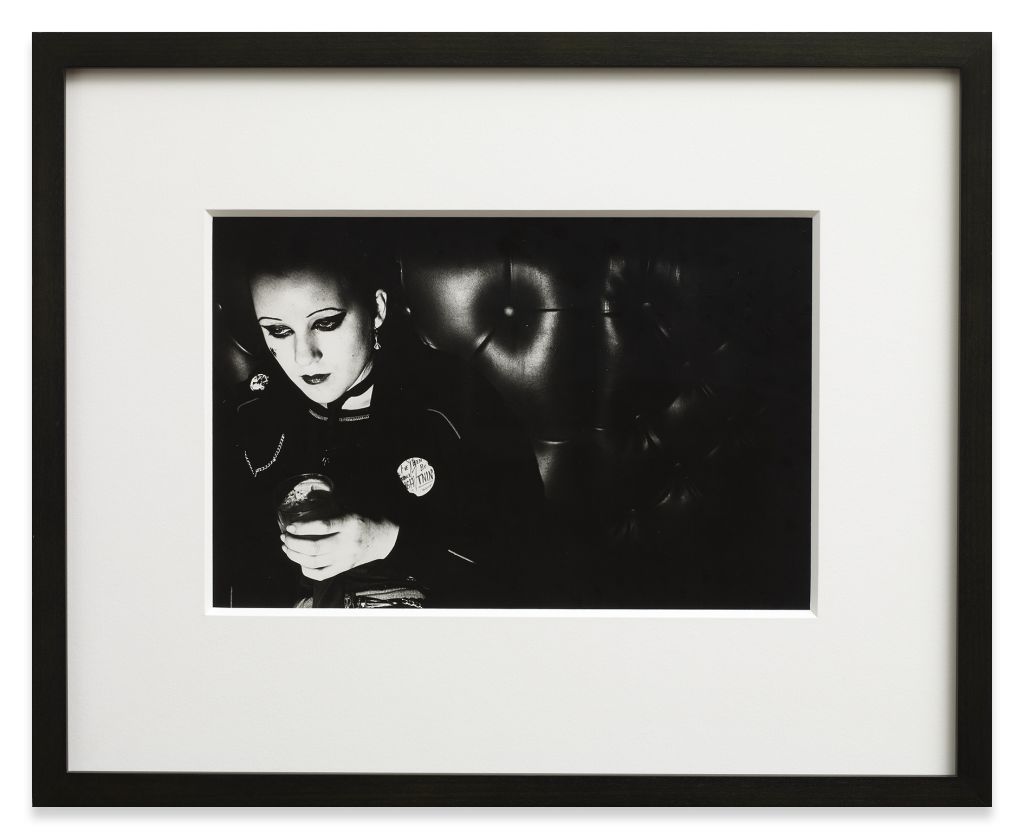

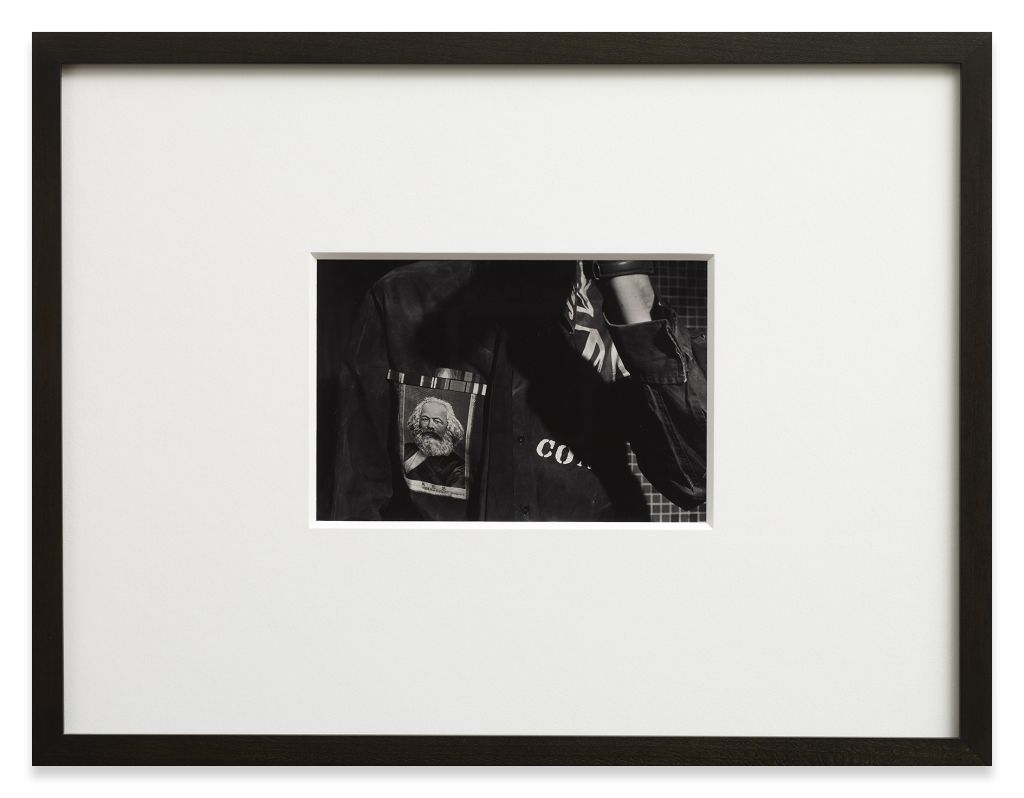

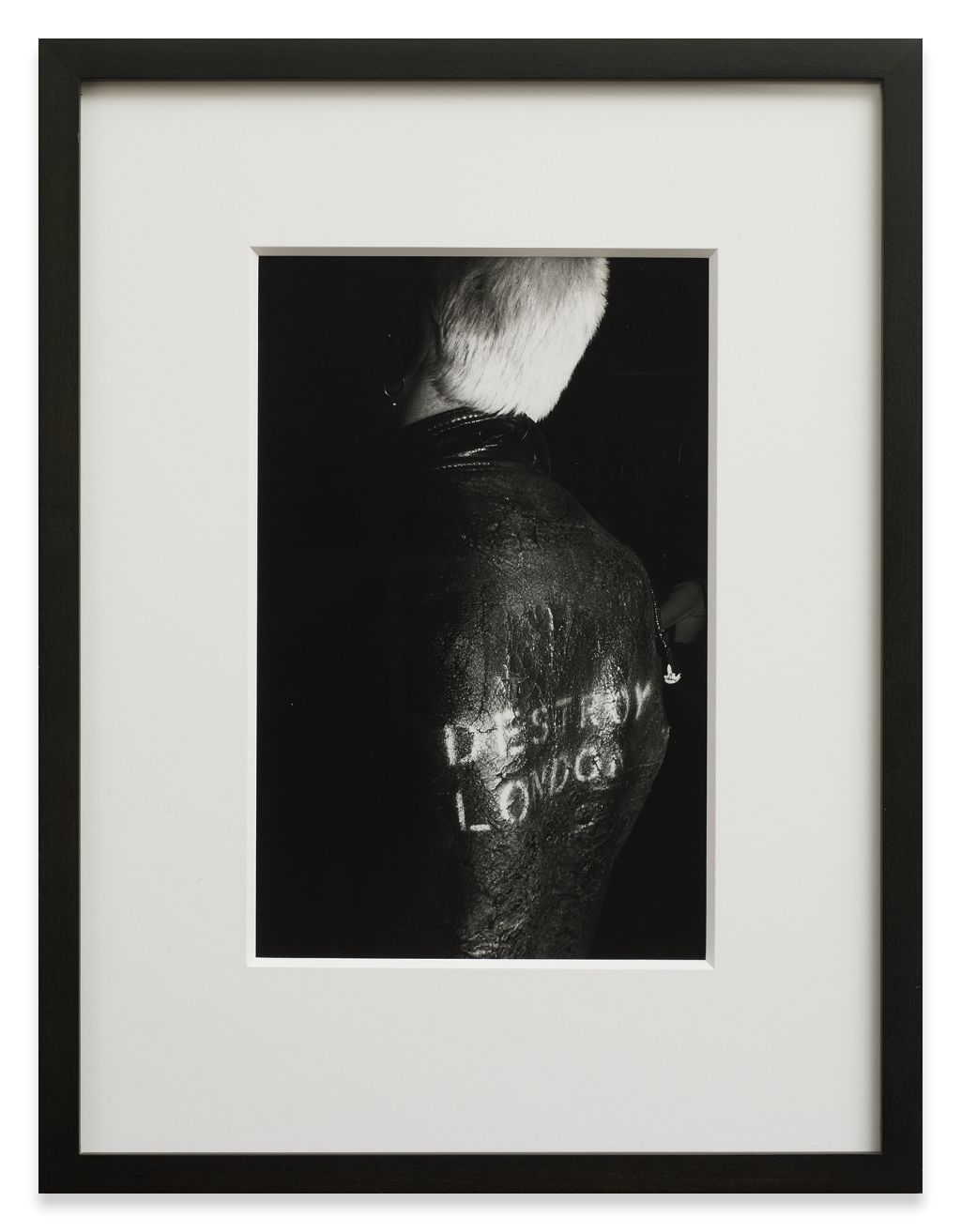

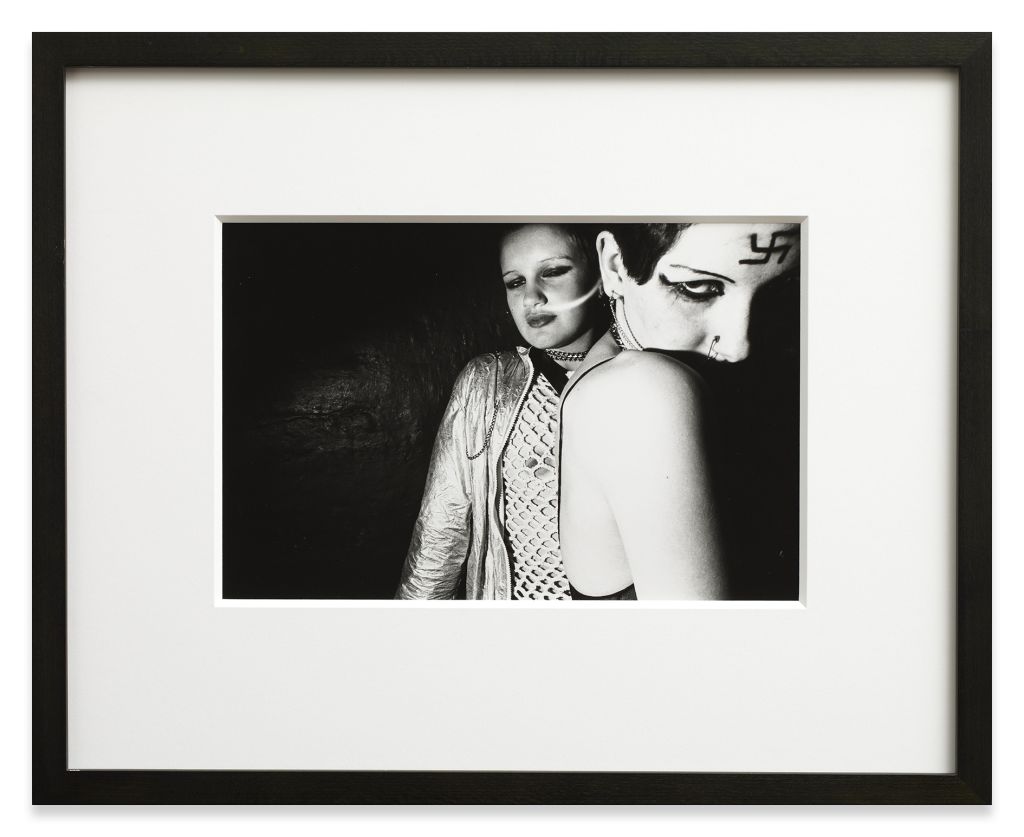

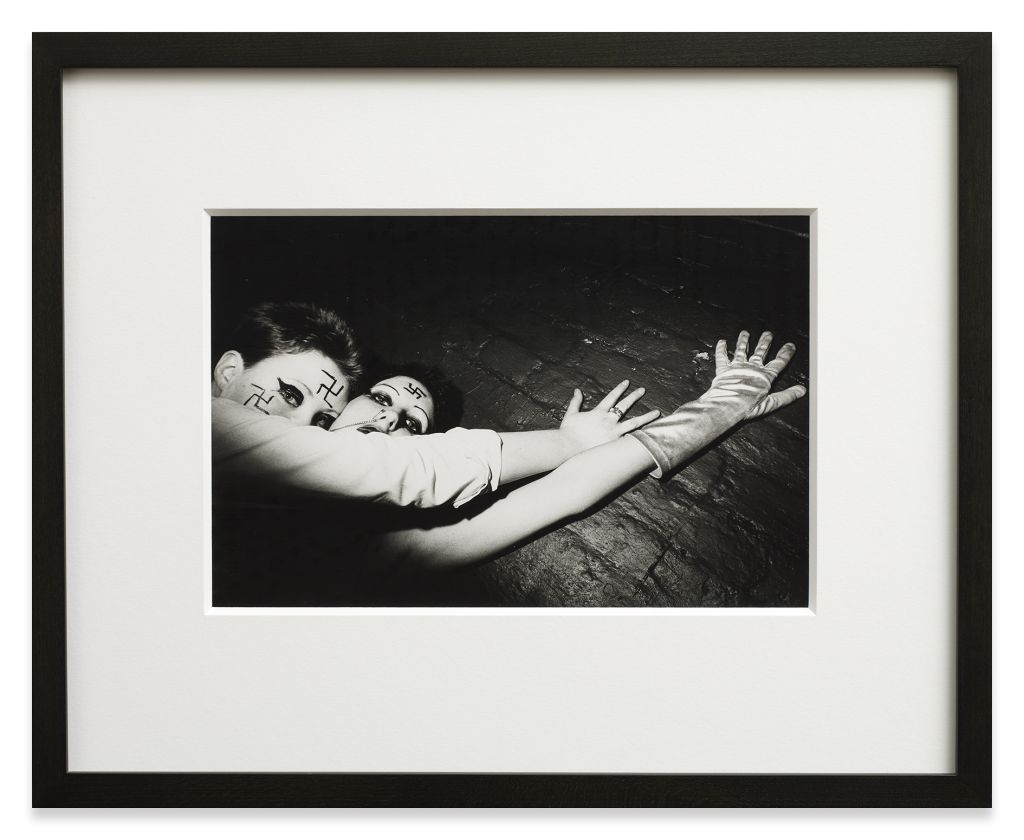

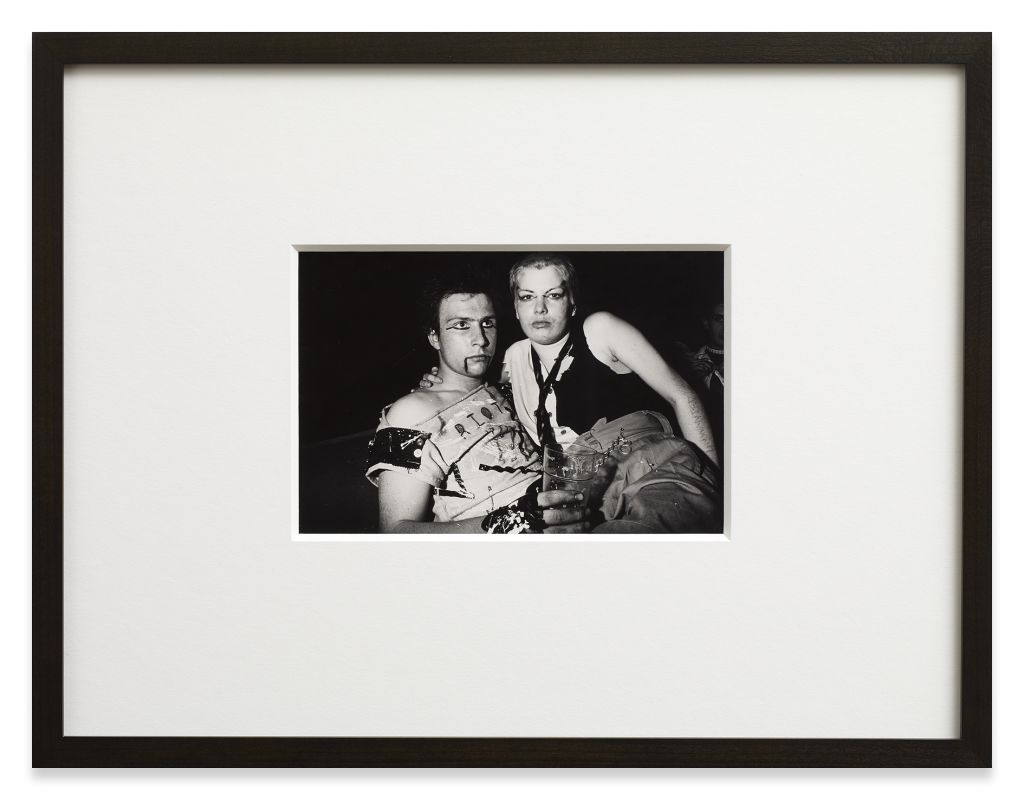

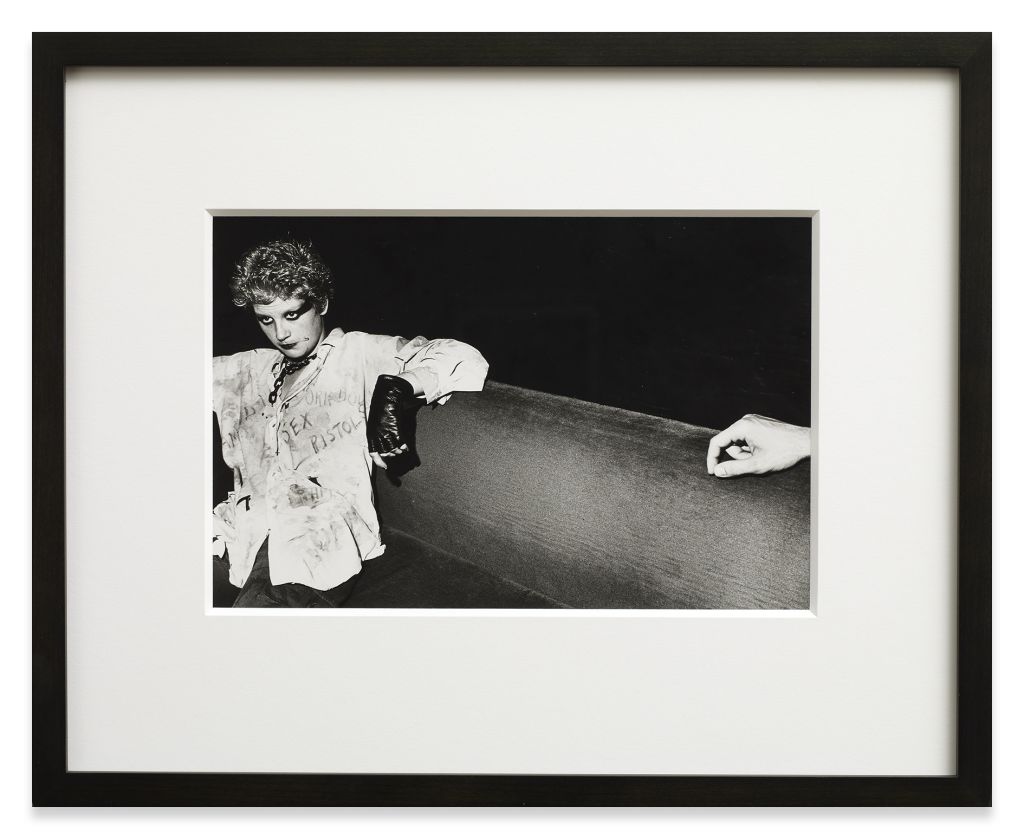

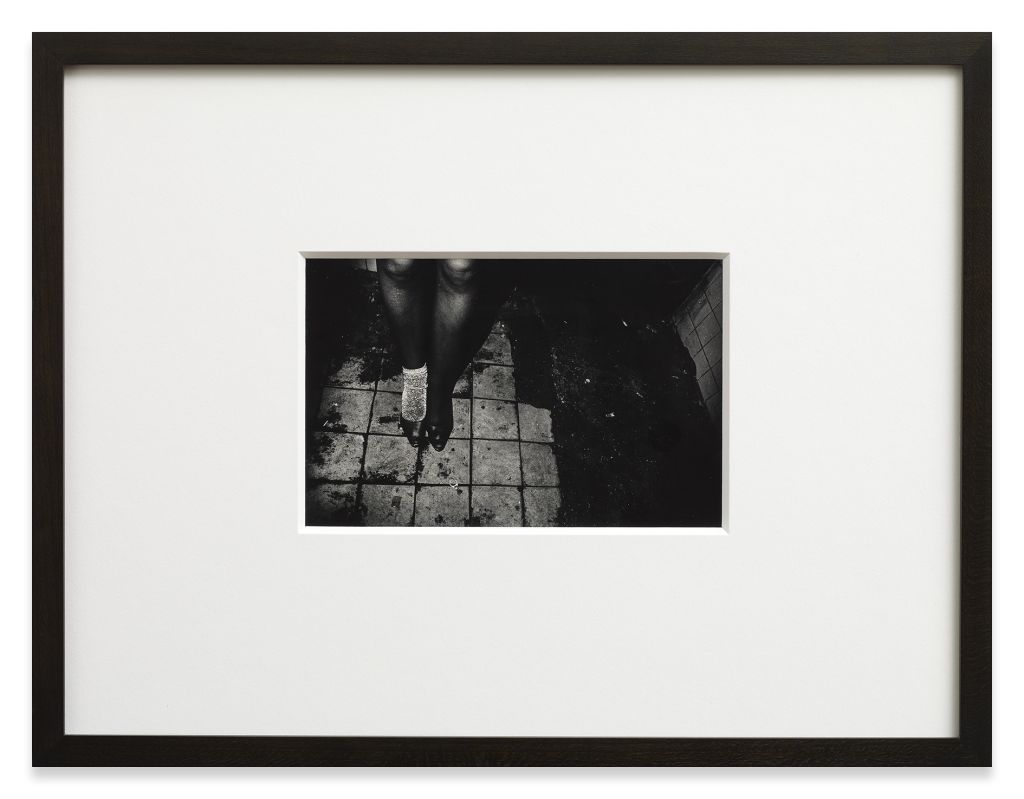

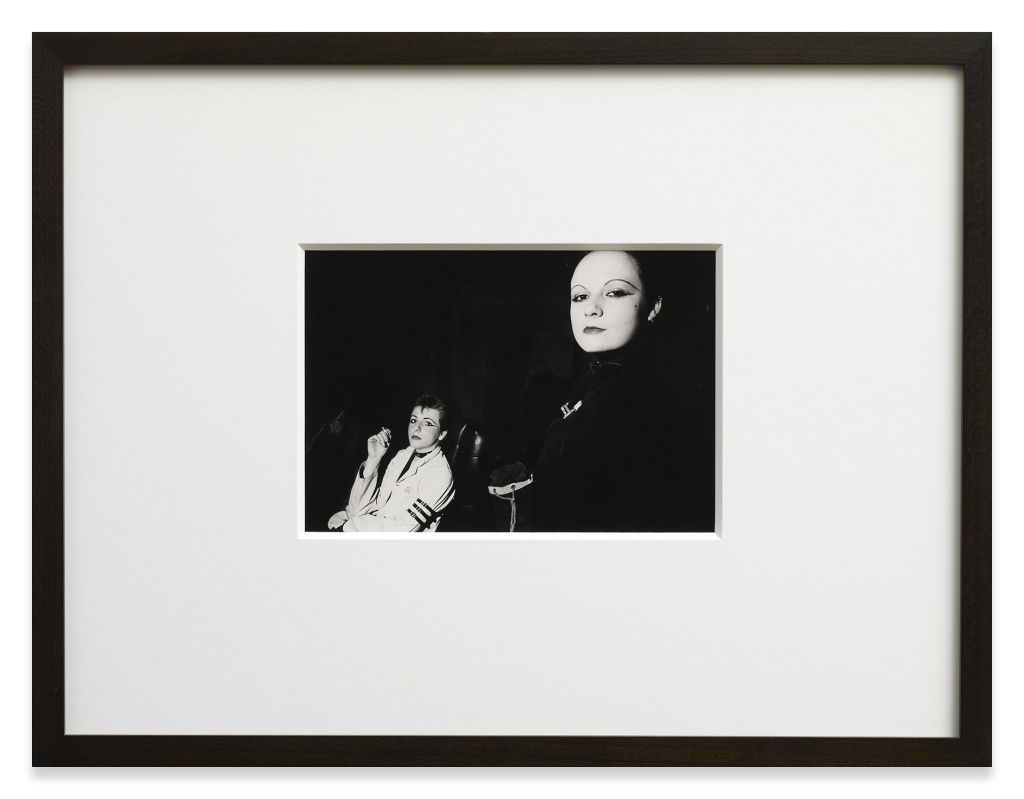

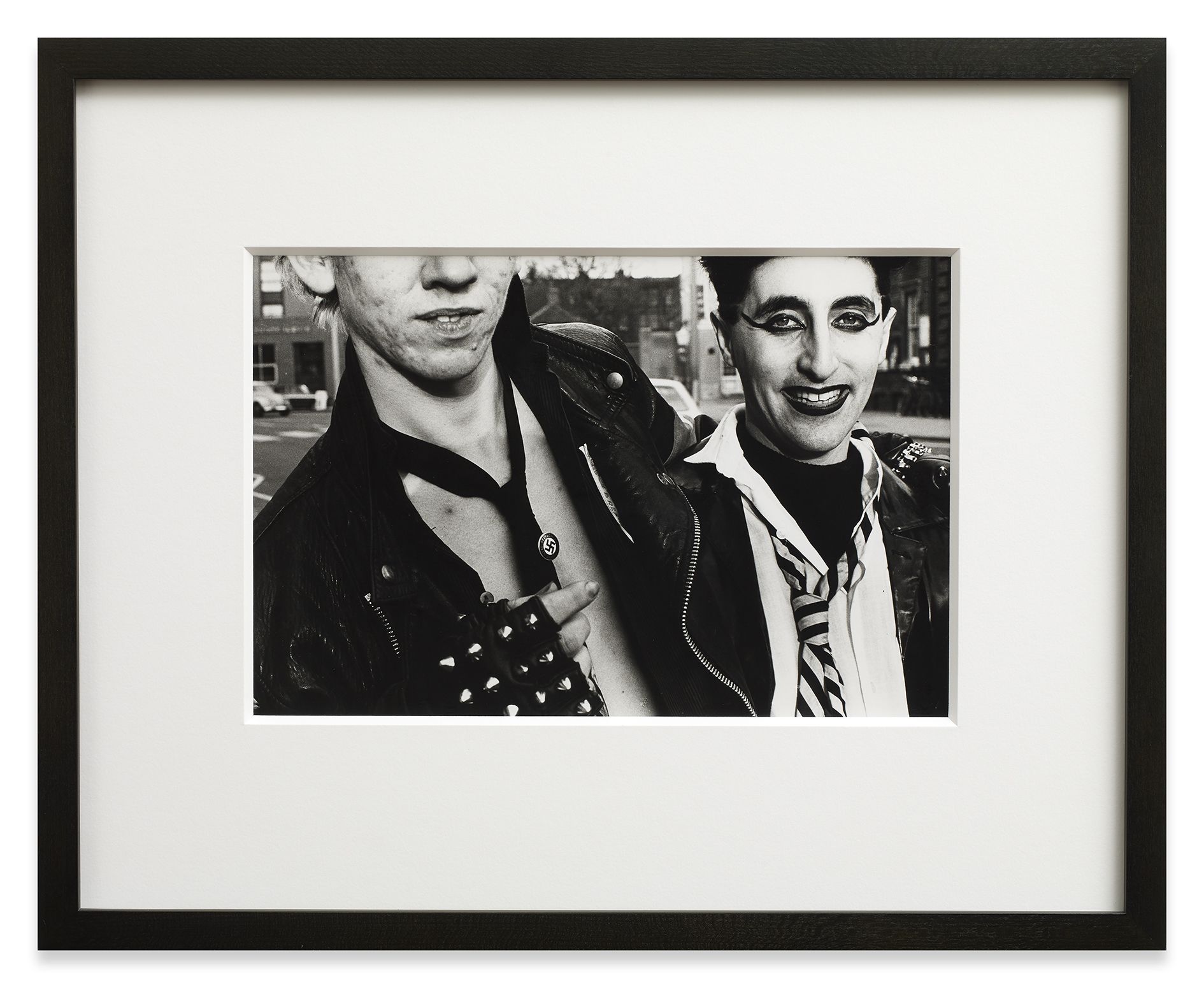

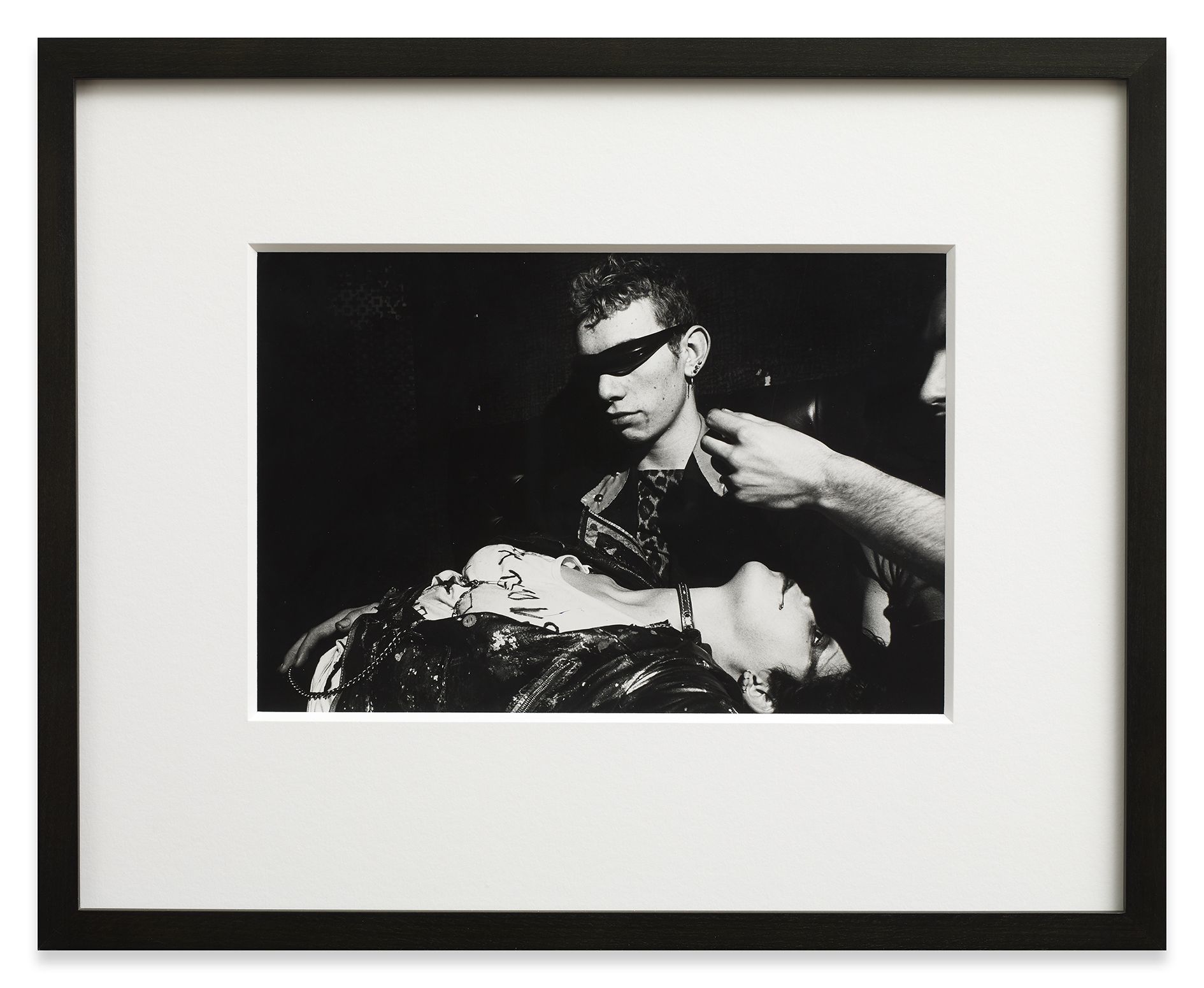

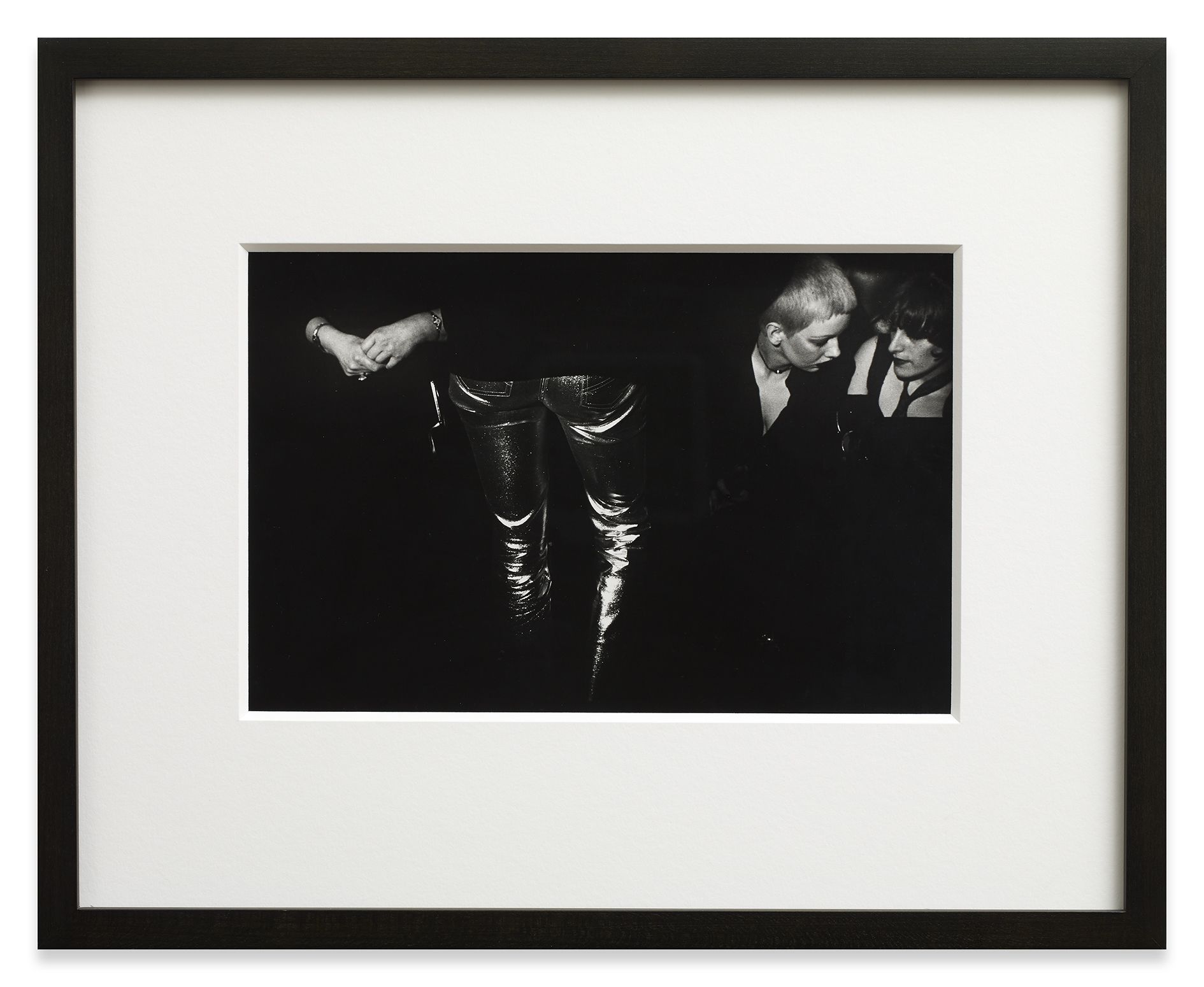

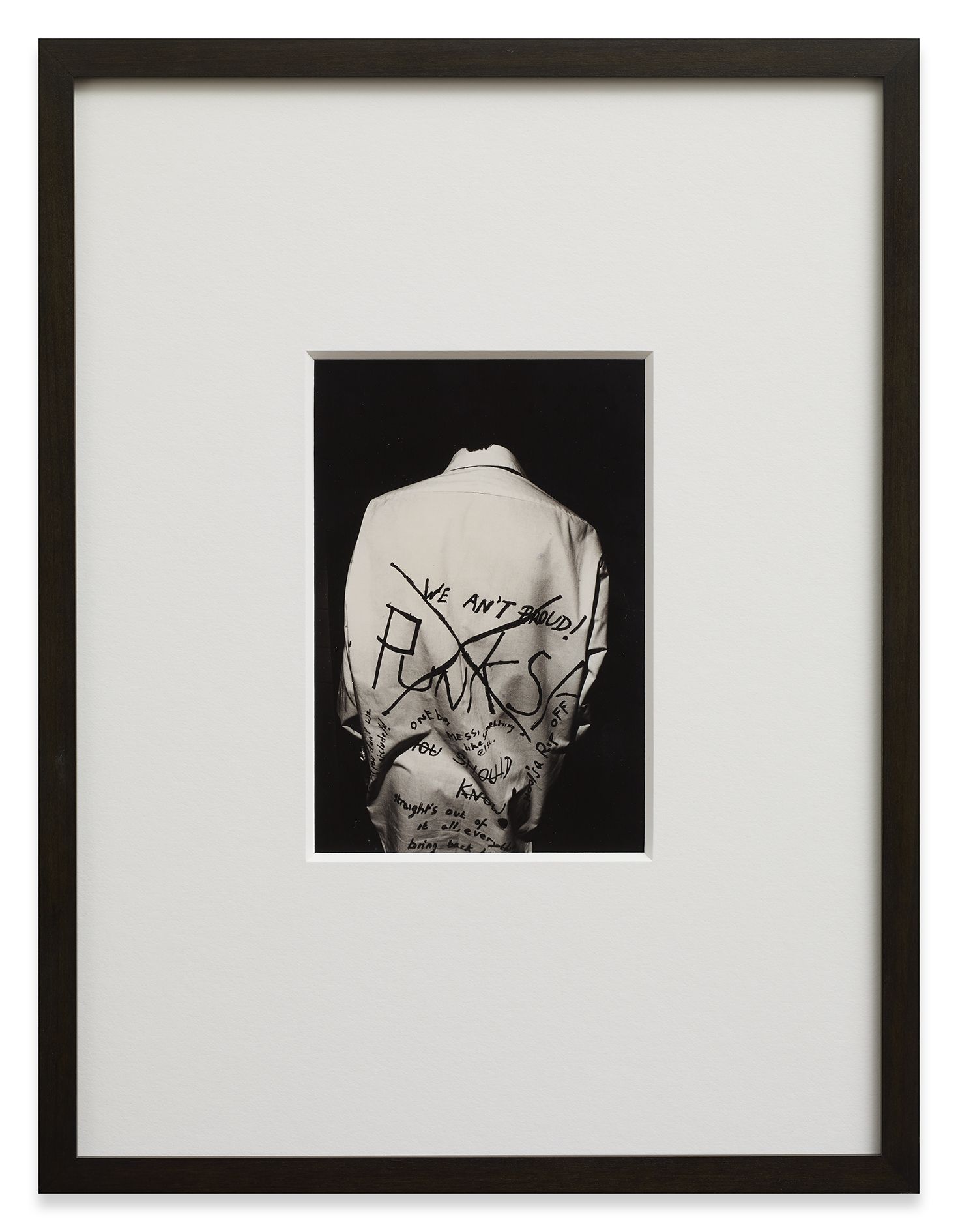

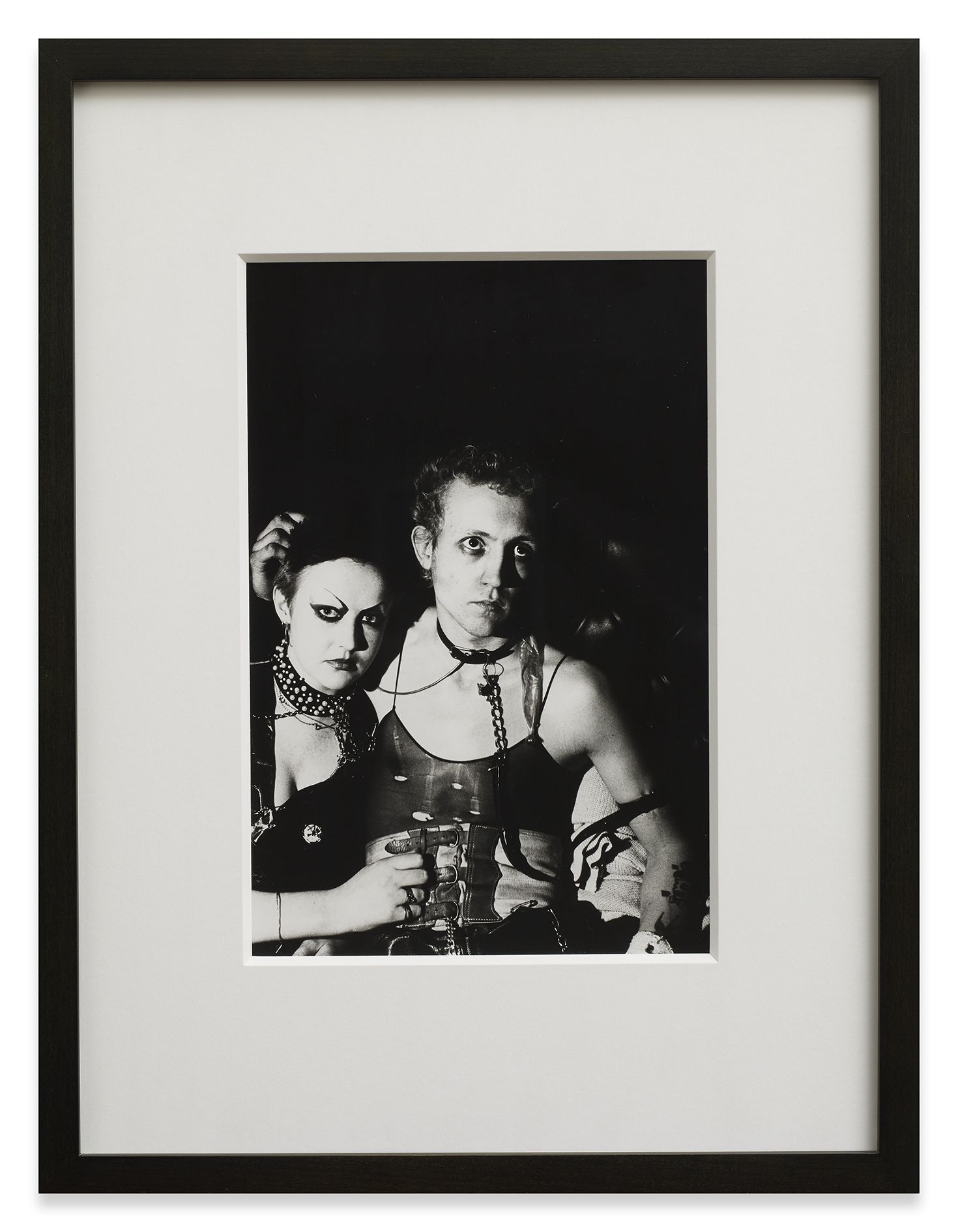

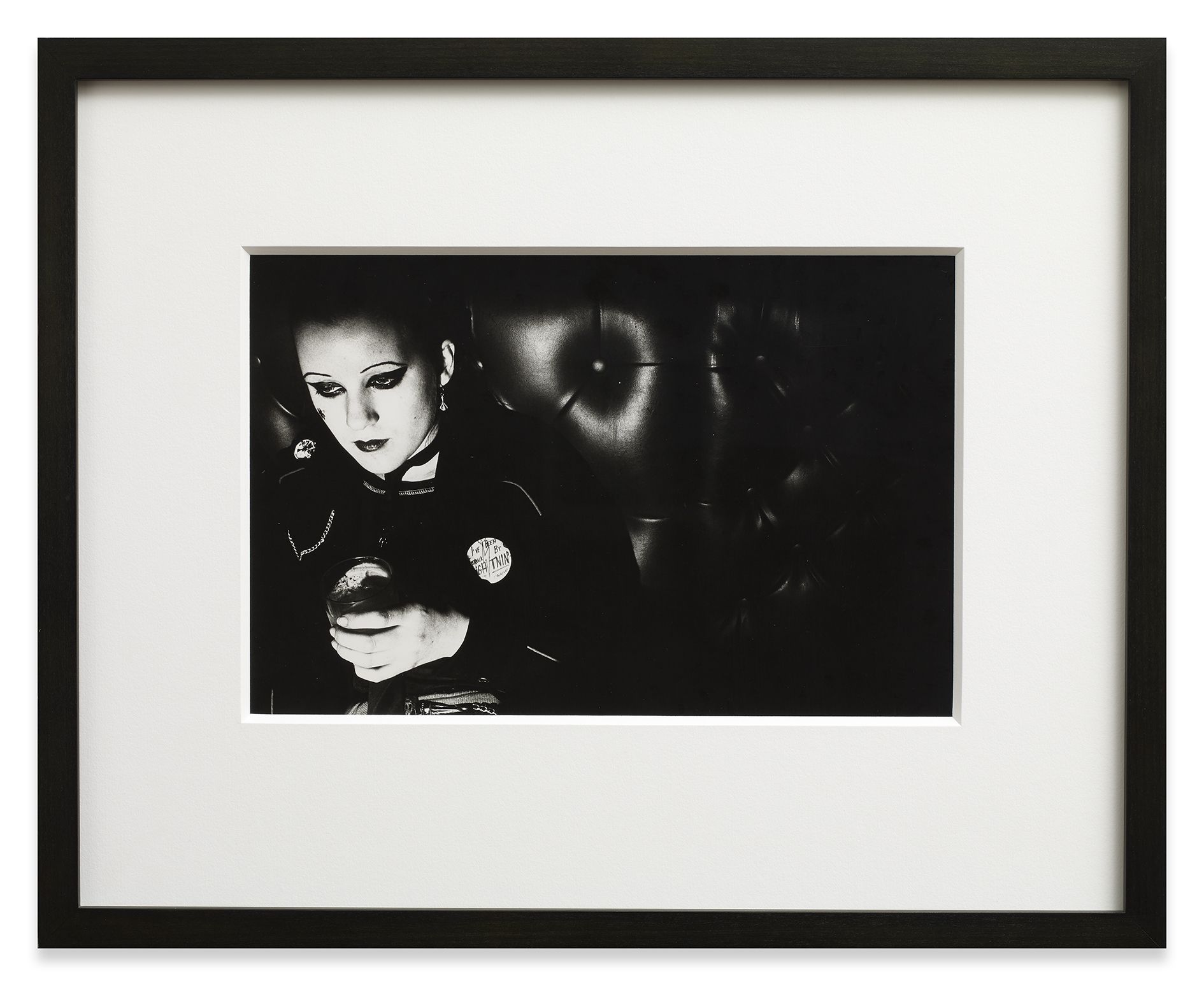

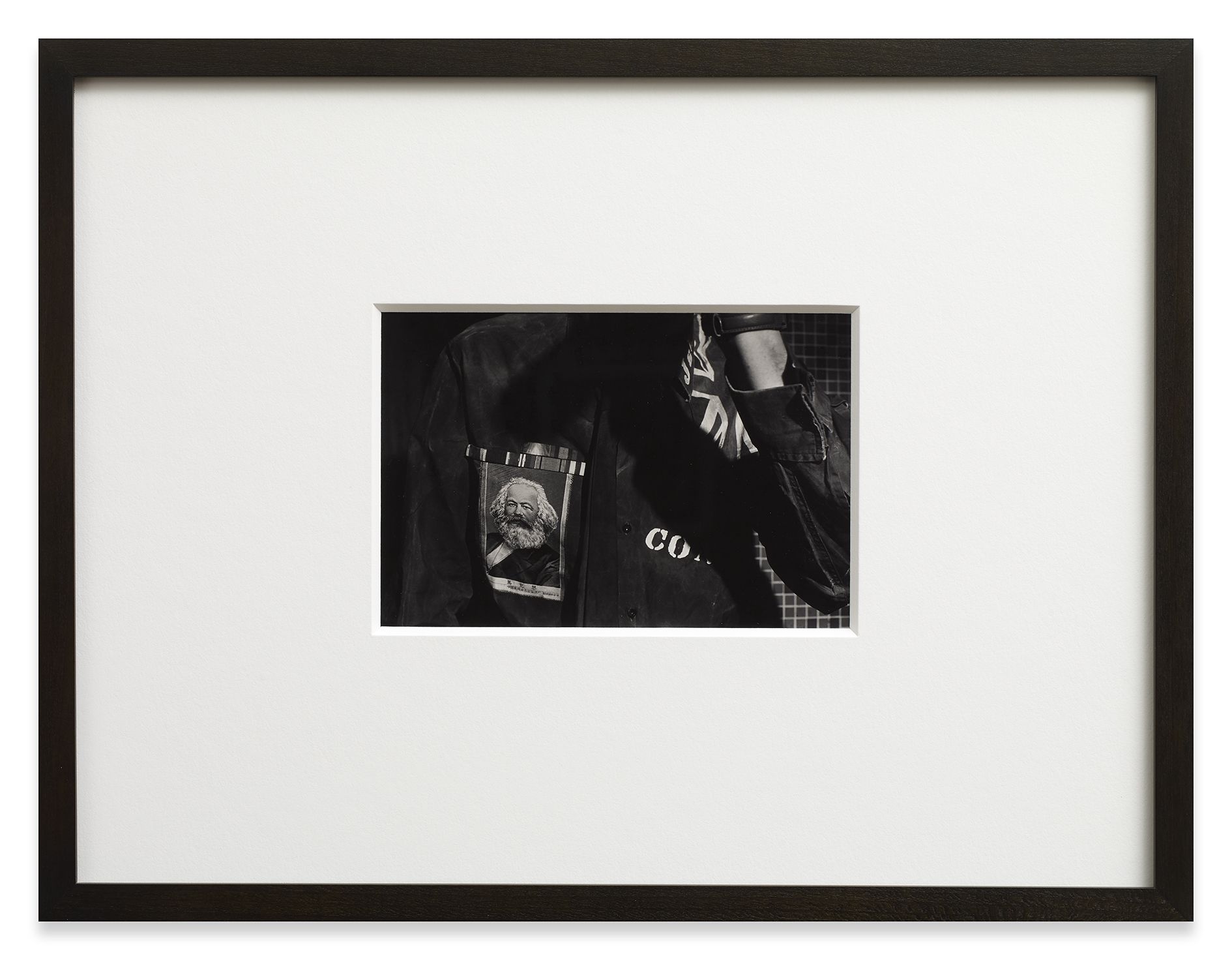

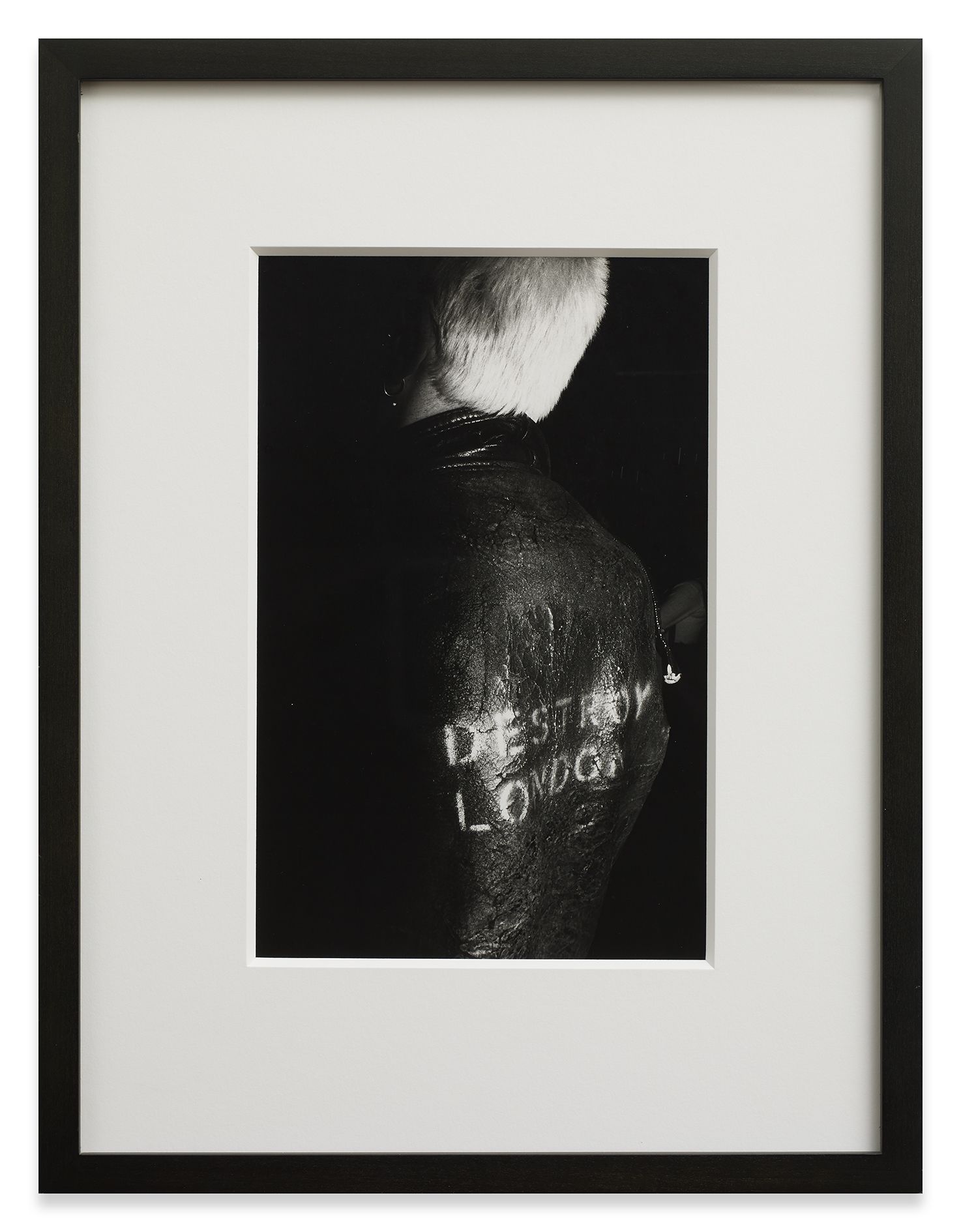

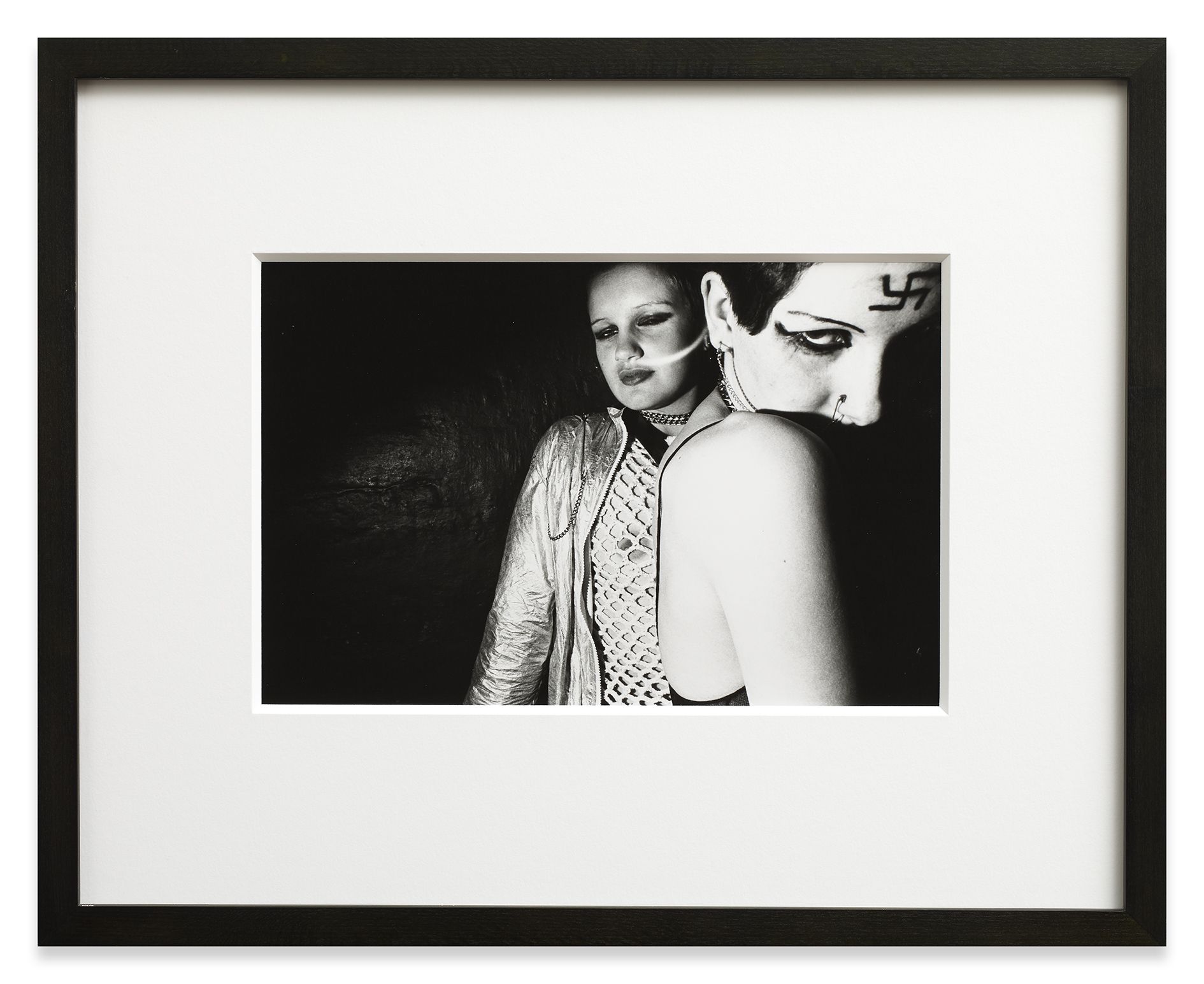

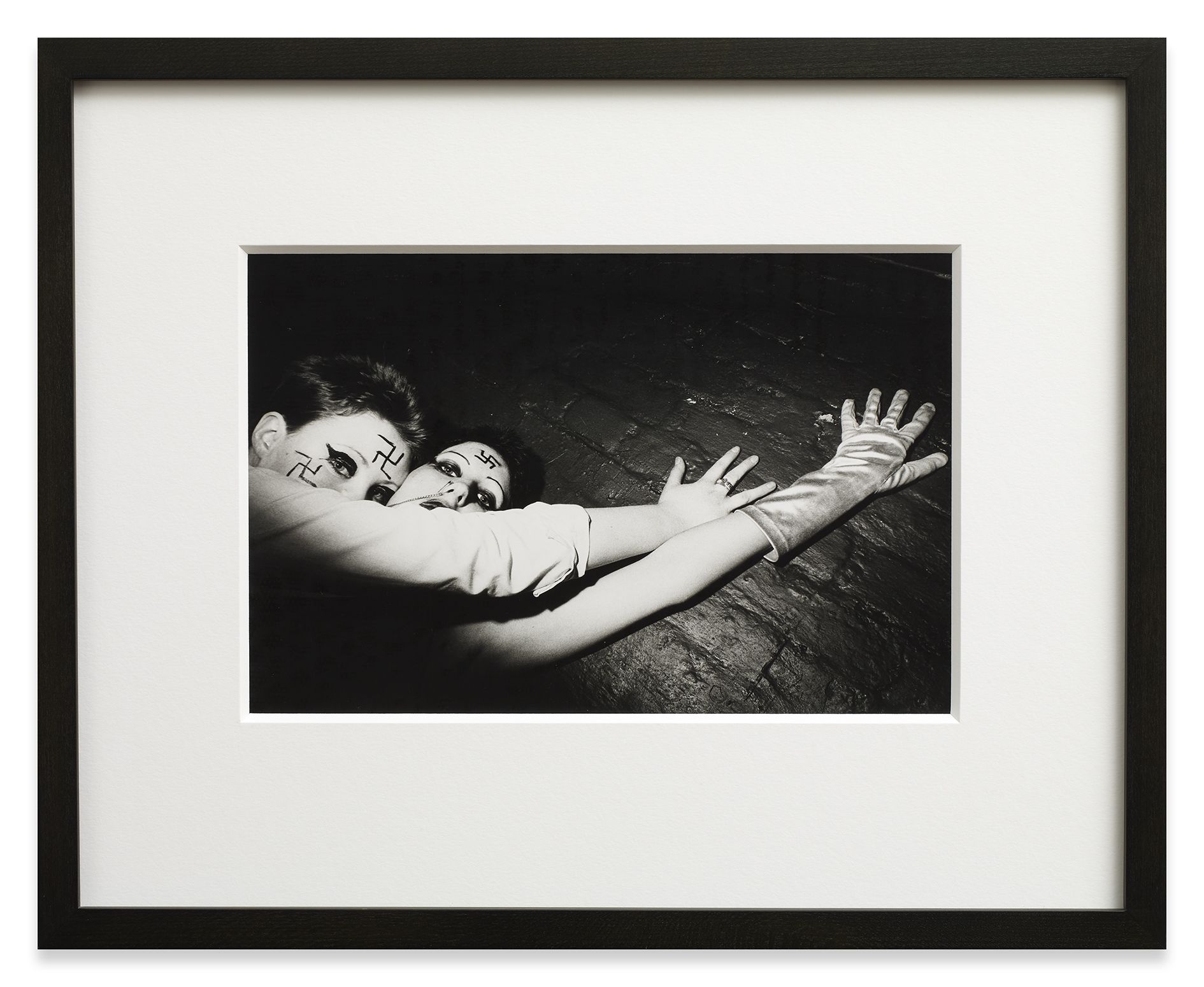

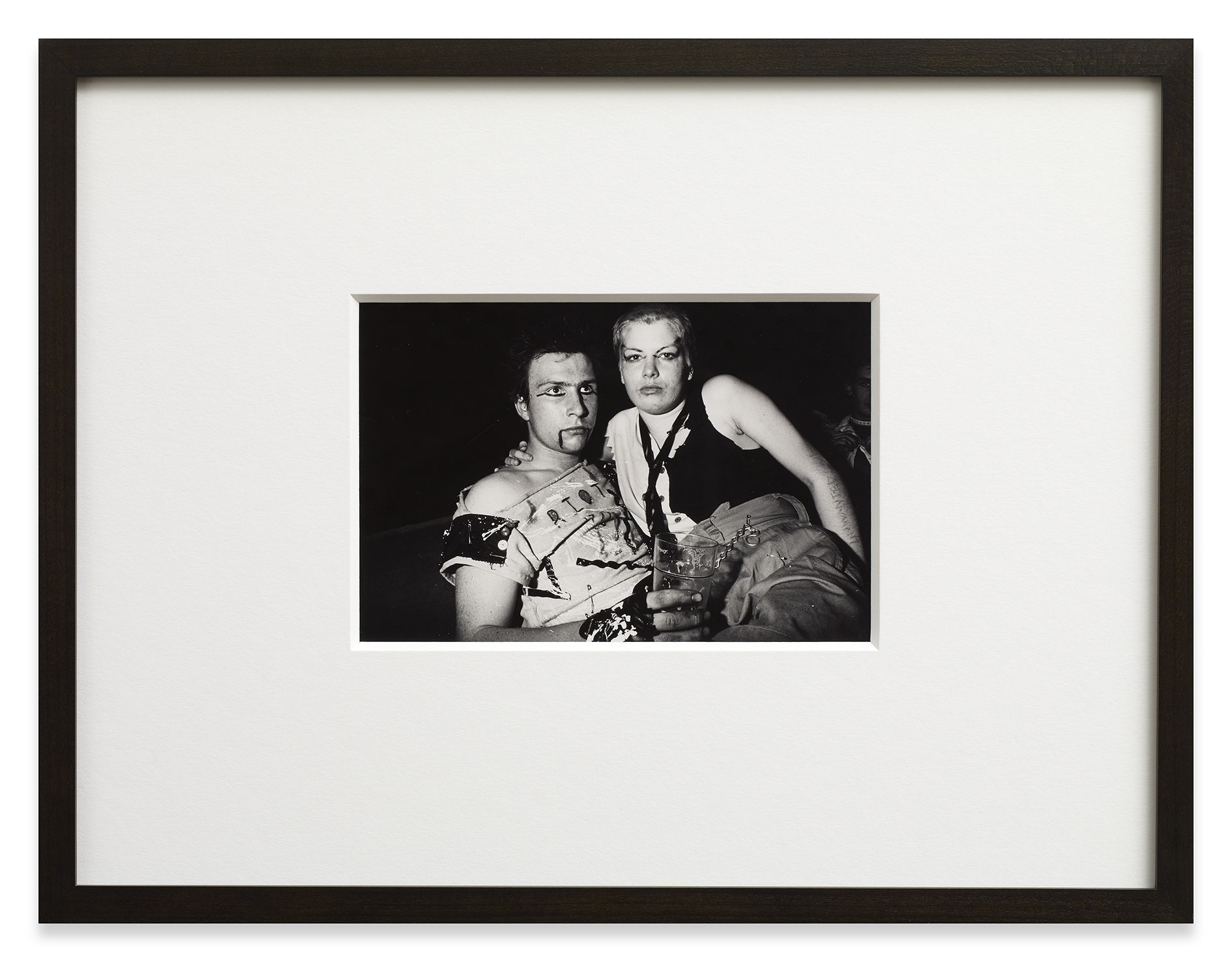

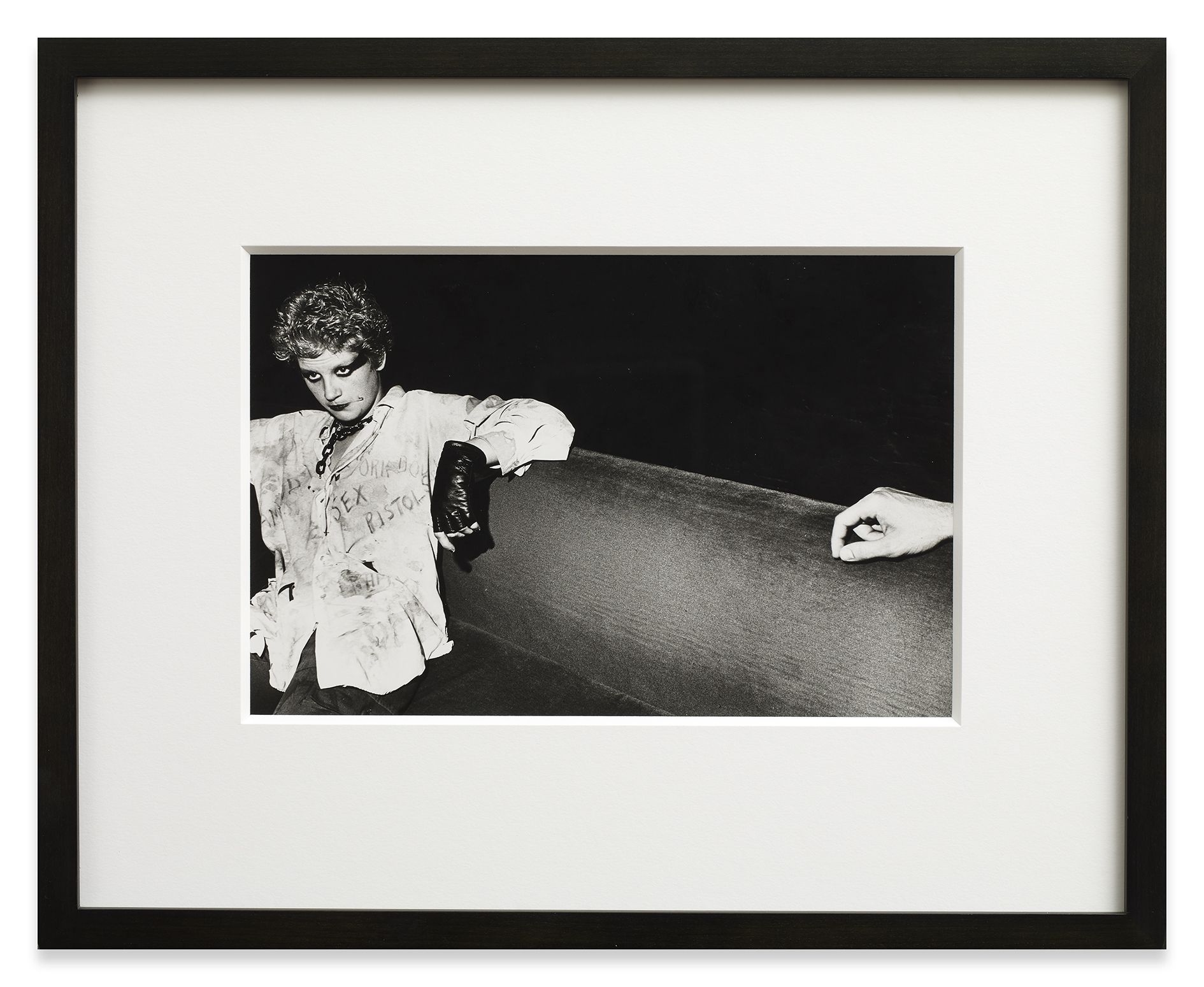

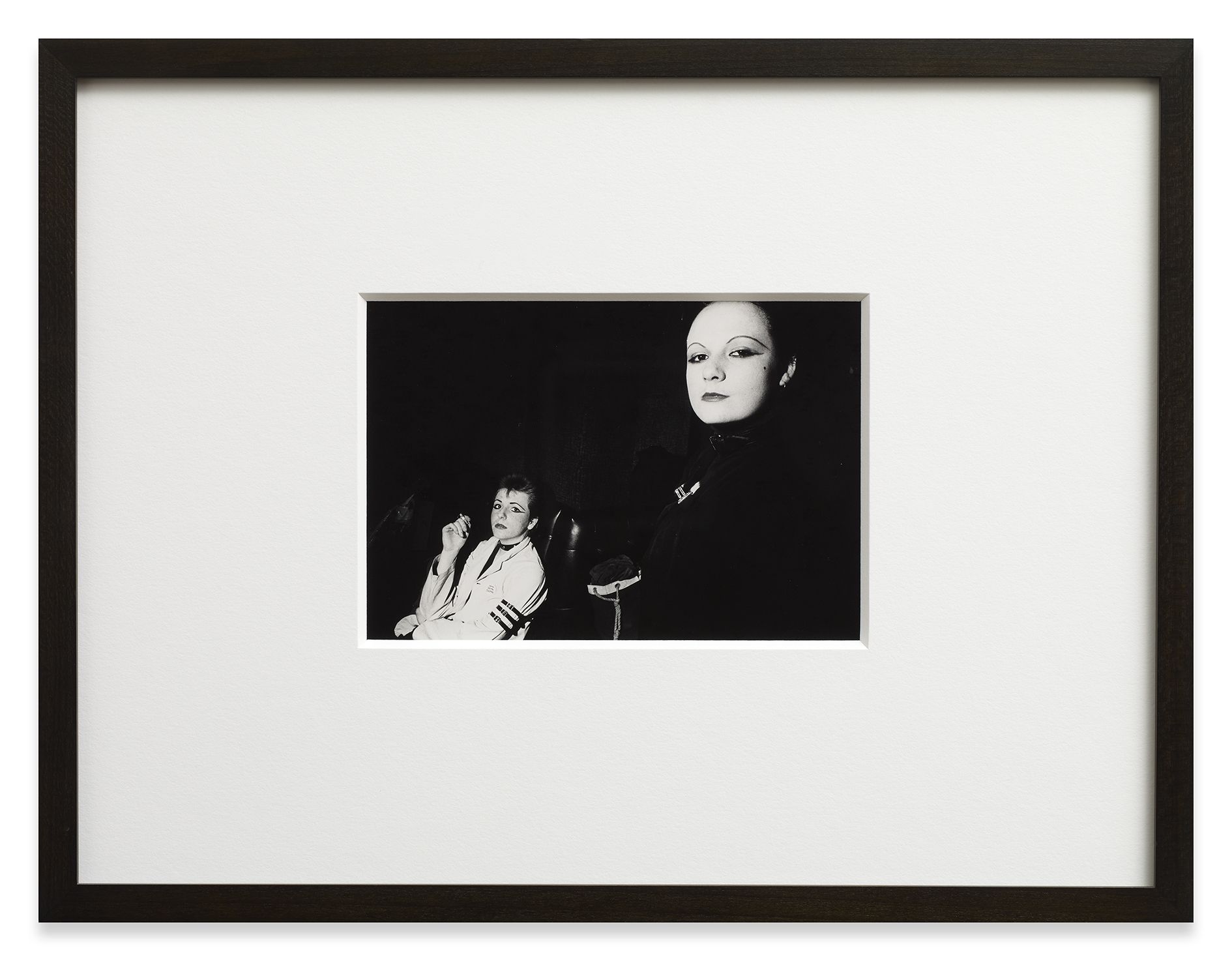

The dawn of the punk era and the societal changes it heralded roughly twenty years prior to the YBAs are presented in Karen Knorr and Olivier Richion’s photographs of punks in the anarchic clubs of London’s West End in 1976 and ‘77. They self-consciously pose rather than being the subject of a simple fly-on-the-wall documentary style, the subjects, notably mostly women, thereby appearing both candid and confrontational, sharply lit by the flashgun. A few years later, Knorr’s series Belgravia would show the wealthy elite of early Thatcherism, captioned by descriptions of their everyday lives or fragments of conversation that complicate the reading of the image and edge the portraits towards caricature. Both punks and Belgravians are revealed as exclusive, self-policing societies, equally concerned with exclusivity, dogma, creed and social camouflage.

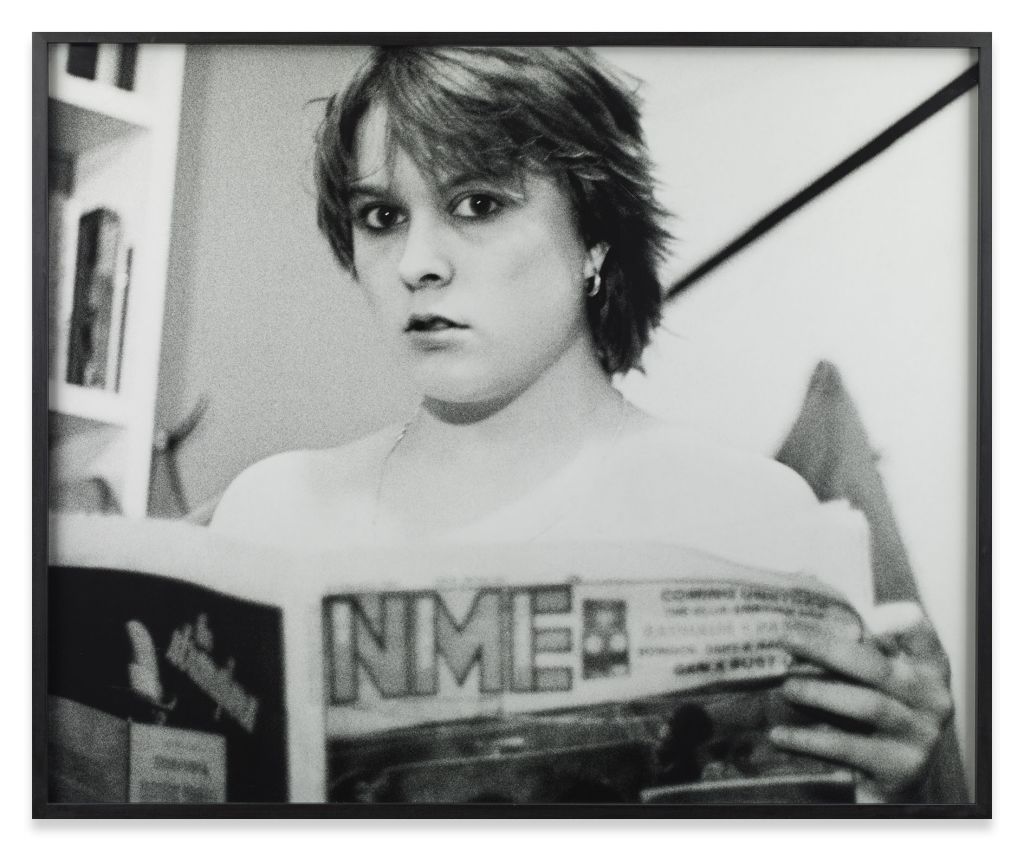

As the first blaze of punk came quickly to an end, it was followed by an atmosphere of requiem, elegy and machine music cults of alienation, responding in part to a UK economic and political climate in a state of volatile flux. This was also the era that saw the rise to pre-eminence of computers, coinciding with the popular use of the term ‘post-modernism’ as a cultural shorthand to describe a new experience of society and culture. Peter Saville’s work for Factory Records exemplifies the ways in which pioneering excursions into post-modernity could be brought to the mass markets commanded by popular culture. His record sleeve for New Order’s Blue Monday was a work of art that anyone could buy from the record shop, designed by Saville with full autonomy from the band and Factory’s chaotic embassy of creative ideology.

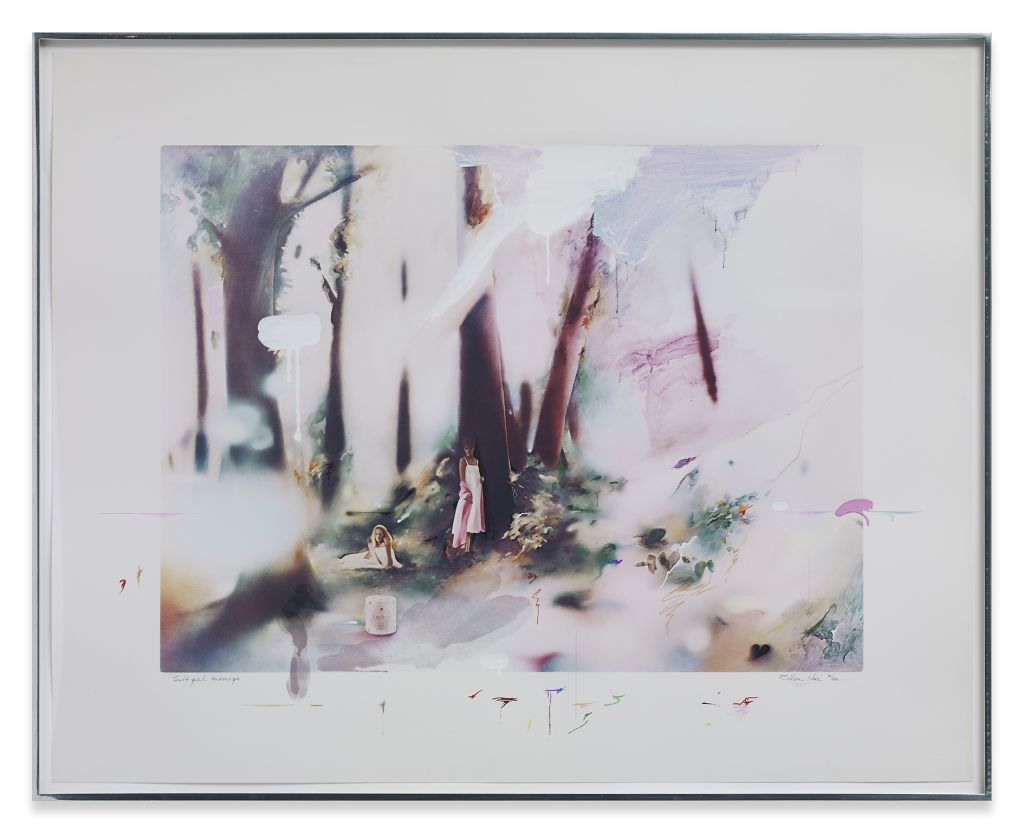

Saville’s work maintains the dualism between ‘cold’, minimalist, scientific-industrial flawlessness, and ‘warm’, luxurious or glamorous romanticism that had been pioneered by Richard Hamilton. His Soft Pink Landscape and Soft Blue Landscape make reference to Andrex toilet paper adverts from the early 1960s, with a small packet clearly slotted into the misty, woodland landscapes, the colour scheme of the product identified the titles. Sat near this is the Diab DS-101, a computer he designed in collaboration with the electronics company that asks questions about the relationship between art and design and the very status of this object as sculpture and/or functioning computer. Likewise, the two studies for Lux 50 – preparatory works for a later painting with the fascia for an functional amplifier embedded into it - question the same dichotomies.

The technical and technological treatment of image in relation to aesthetics, sociology and irony that Hamilton established and that was also central to Saville’s work would in turn be inherited and re-examined by Hirst. He is also present in this room with an early medicine cabinet Satellite, named after the Sex Pistols’ B-side. Unlike the video work at the start of the exhibition, the rough-and-ready ‘calling card’ style is not present; instead it is orderly with a colourful readymade pop art palette. Despite a shared interest in death and decay, it does not necessarily share the same chaotic punk ethos to search and destroy.

The audience and influence of pop and rock music were evidently still vast, fervent and political with the punk movement and its followers offering a creativity that was both sub-cultural and largely independent of and in opposition to the institutions of the art world. The common denominator of these subjects is a radical declaration of identity, image, creativity, autonomy and newness, at a time when Britain was undergoing fundamental technological, political, social and economic changes, the consequences of which are still being played out.