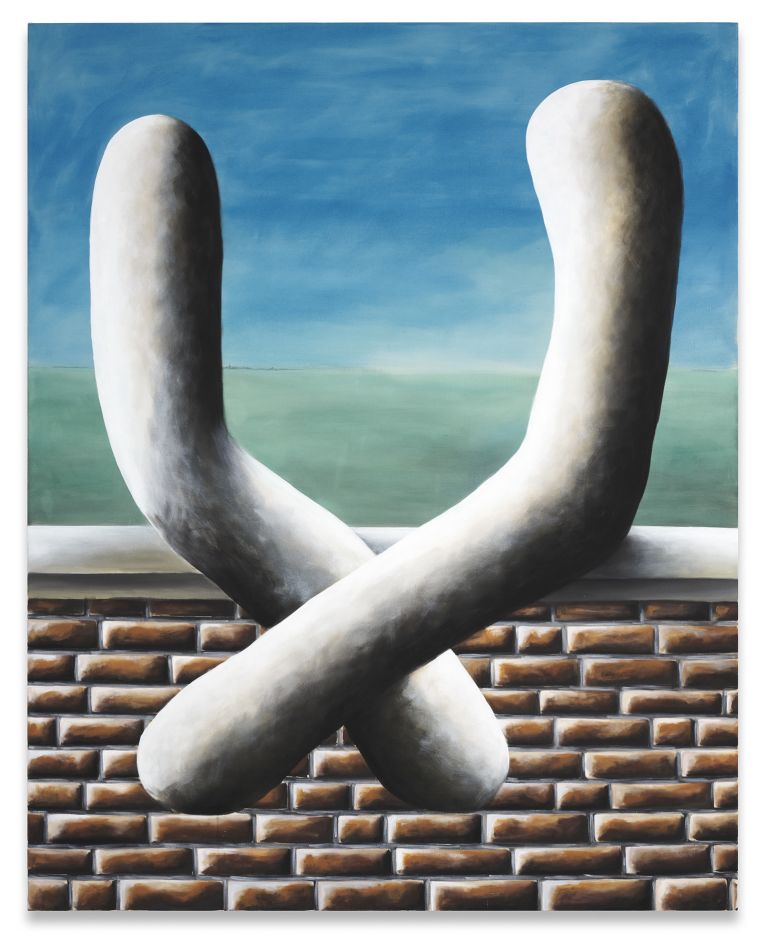

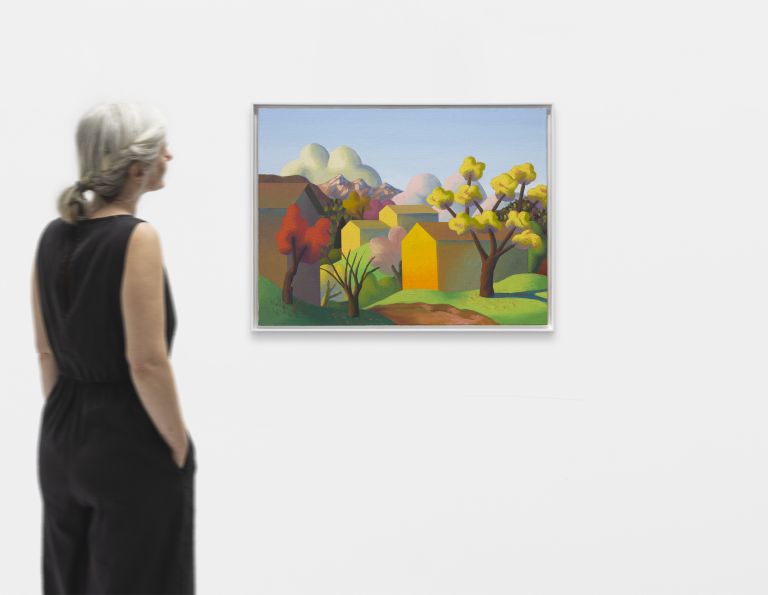

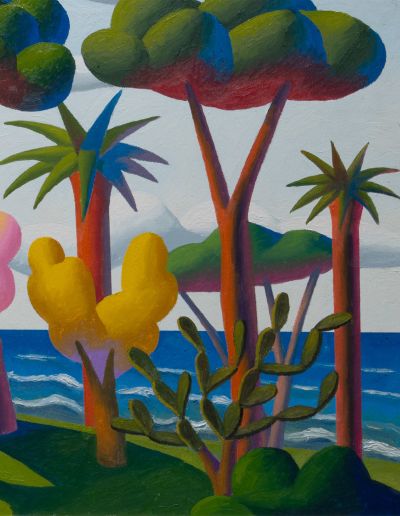

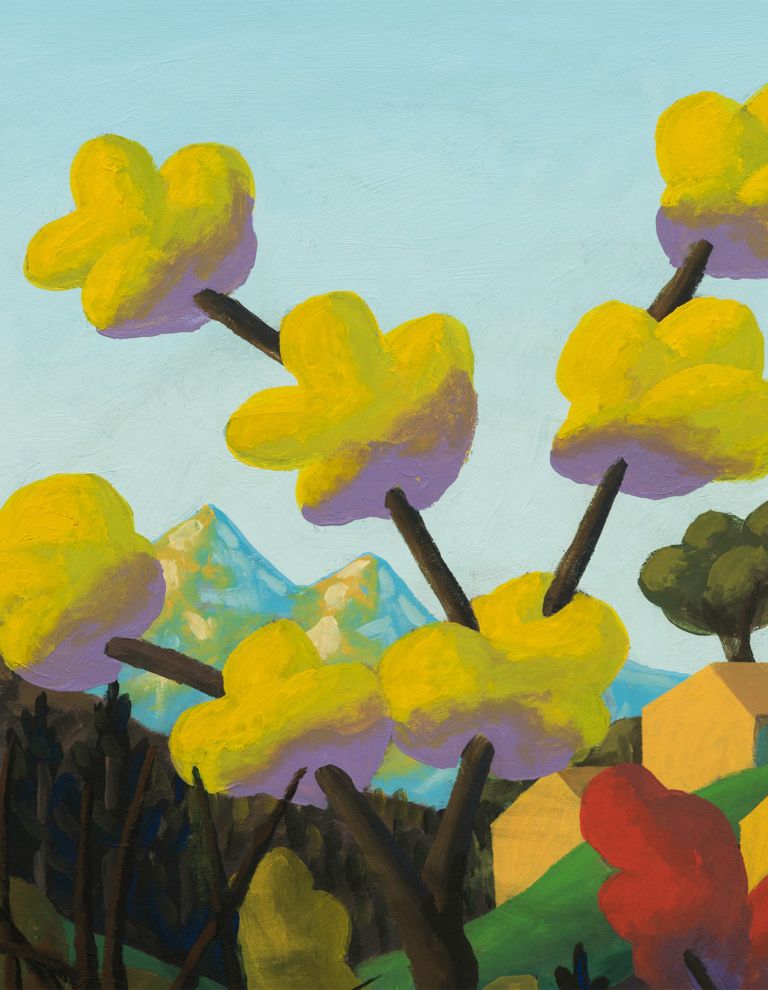

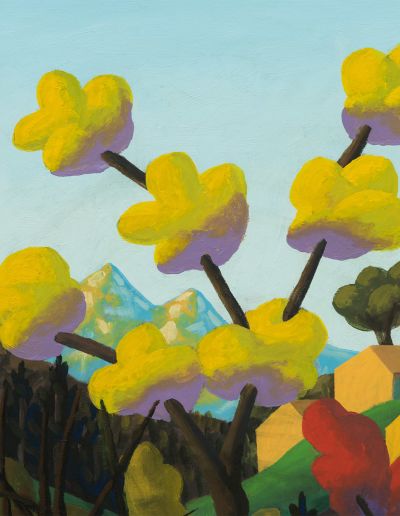

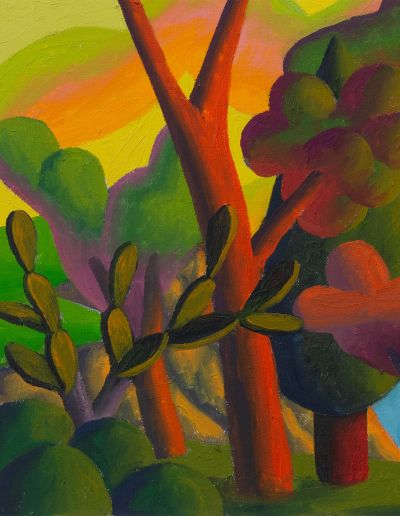

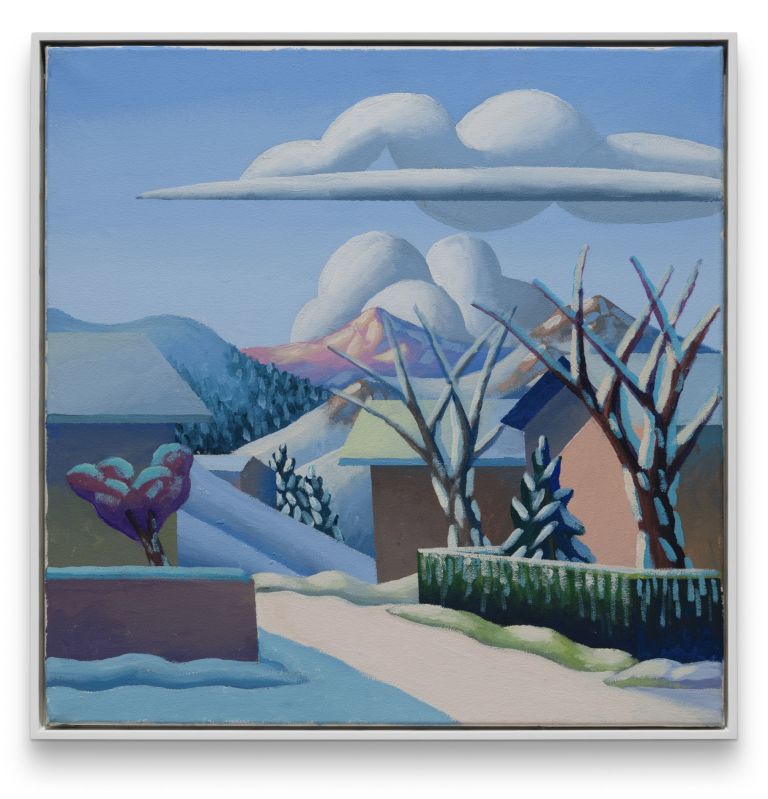

Andreas Schulze (*1955, Hanover) has played a key role in German painting for over four decades. Like Salvo, he was a participant in the heady artistic dialogues around him—in Schulze’s case, Die Neuen Wilden (The New Fauves) of Cologne’s Mülheimer Freiheit group. Yet he developed his own distinctive painterly methods that balance representation and abstraction, adopting styles derived variously from Surrealism, Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism and infusing his scenes of everyday bourgeois life with humor and irony, as well as an intermittent sense of foreboding. At every turn, Schulze both celebrates and defamiliarizes his domestic interiors, urban views and lush landscapes, rendering them strange and absurd through his deft manipulations of paint and compositional space.

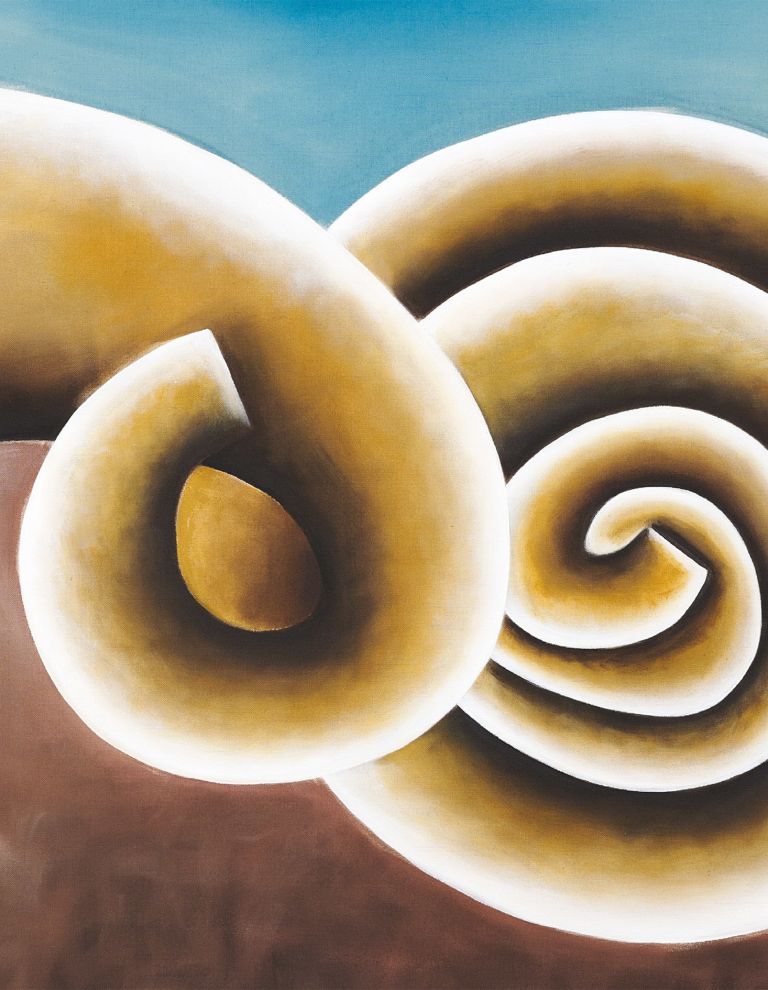

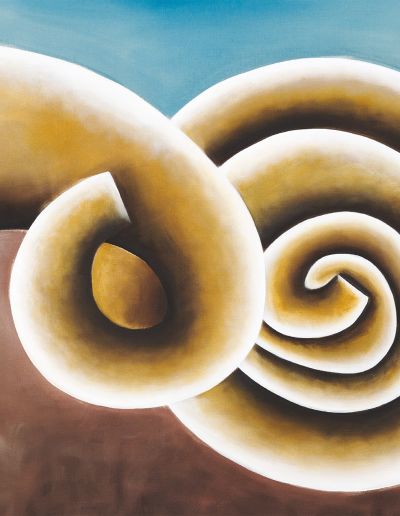

In Schulze’s Untitled (Black cloud) (2024), for example, flowing diagonal bands cut through the sides of the work, pouring down its surface in a nod to Abstract Expressionist painter Morris Louis’ celebrated “Unfurled” canvases. Here, Schulze plays overtly with our desire to spot figuration in even the most abstract passages, with the “black cloud” of the work’s title hanging heavily over a pale yellow horizon.