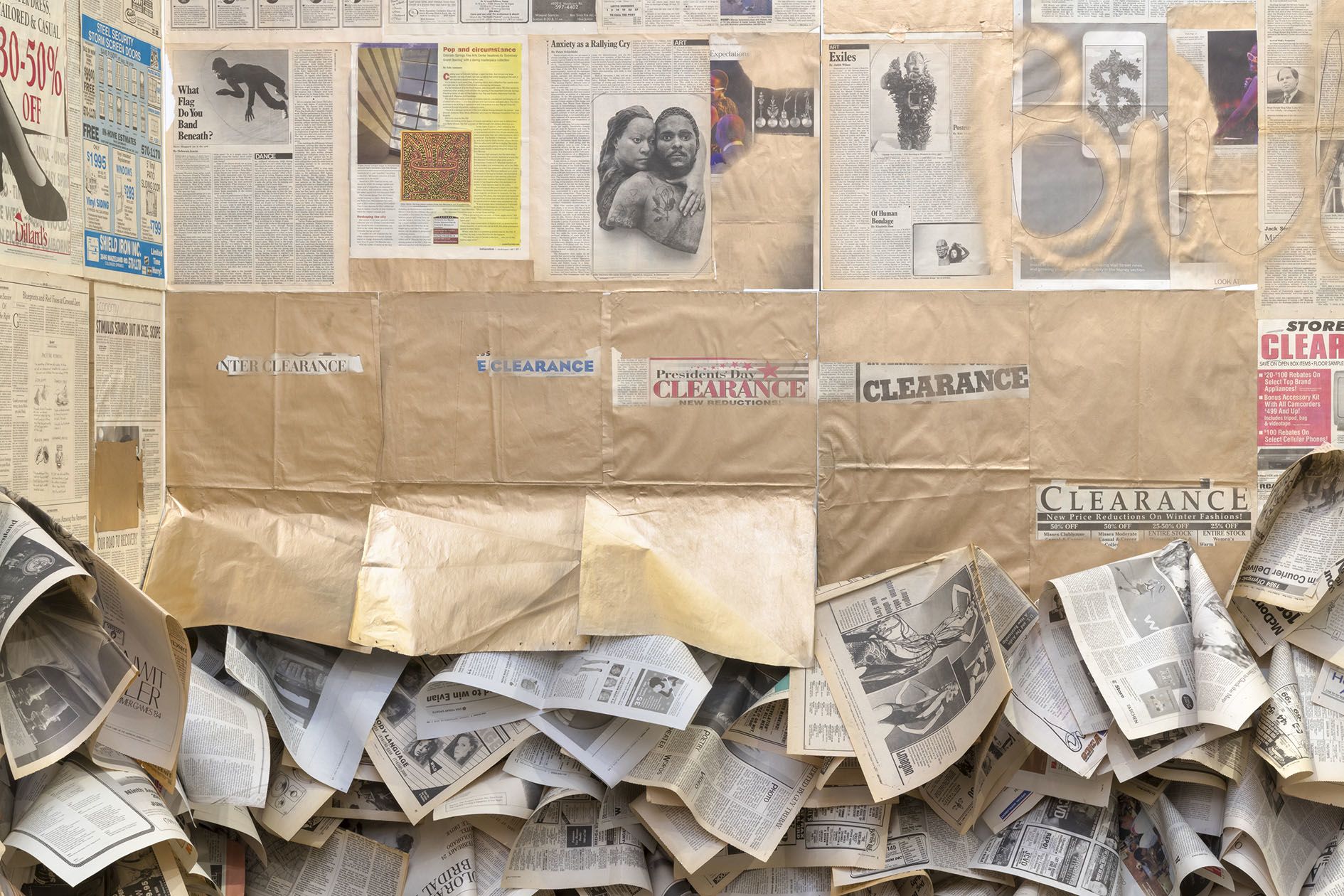

Bulemia was first presented in 1988 at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore as part of Art as a Verb: The Evolving Continuum, an influential exhibition of thirteen African American artists working outside the confines of traditional painting and sculpture. Accidentally discarded when that exhibition closed, the imposing work went unseen until it was recreated in 2018. Then, as now, the source of the papers is both Nengudi’s and her mother's collection of newspaper spreads that over the years they found to be worth saving.

In this same period of the late 1980s, Nengudi had been developing a concept of “Bulemia” as a utopian state ruled by creative forces and Black voices. She produced a half-hour radio program, funded by National Public Radio, that she described as a “crazy-quilt of conversation and music” with words from fellow artists Charles Abramson, Carol Blank, John Outterbridge and Kaylynn Sullivan, as well as cameos by the likes of musicians Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor. “BULEMIA is not a disease but a state of mind,” the program’s poster announces, “used as a metaphor for exploring the nature of creativity.”