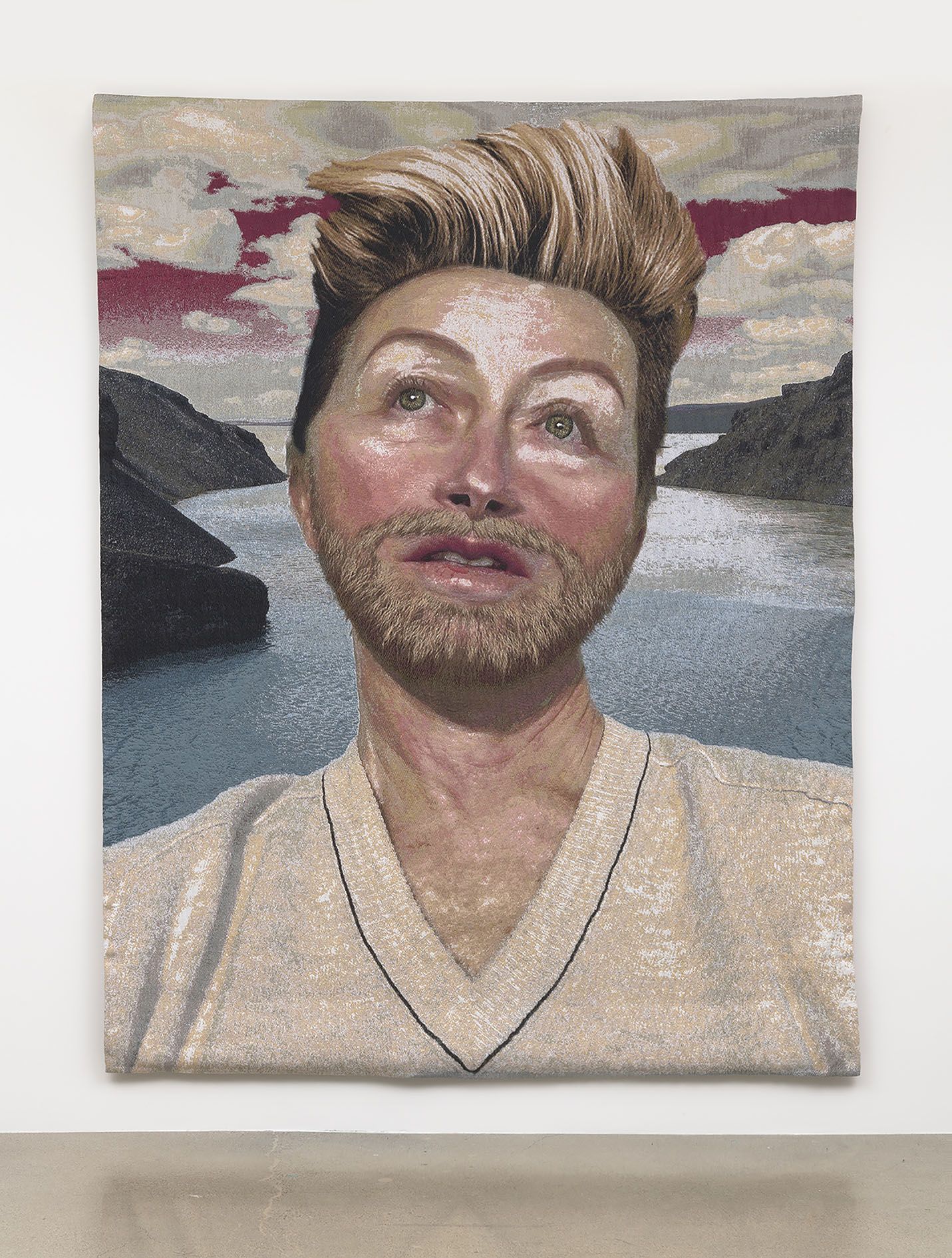

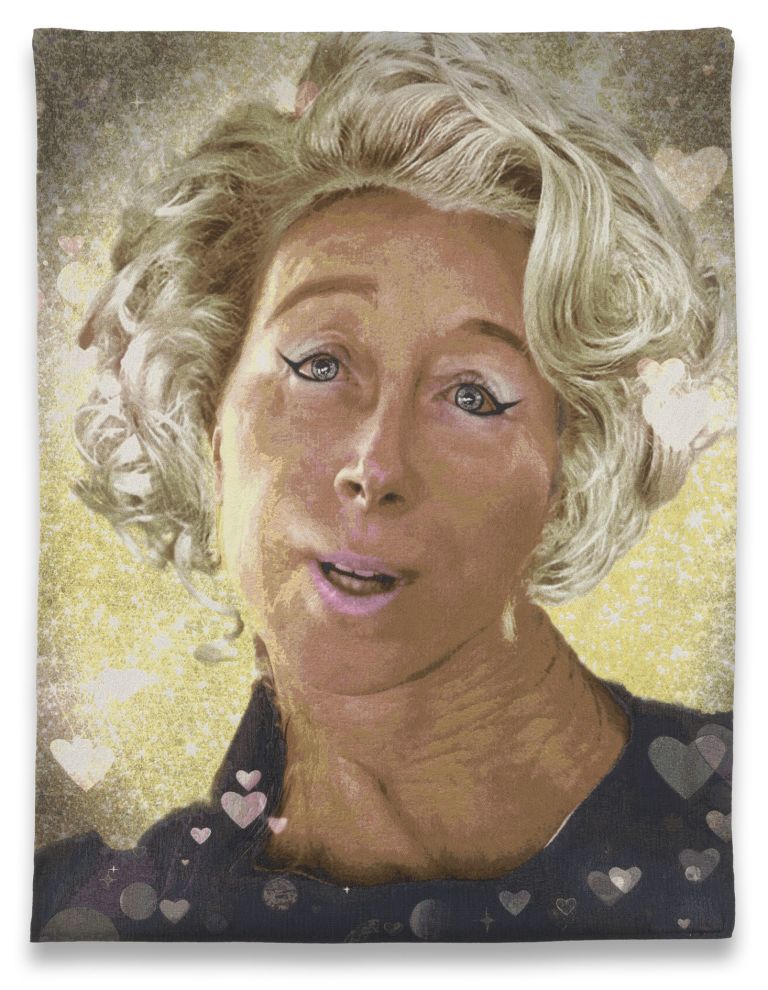

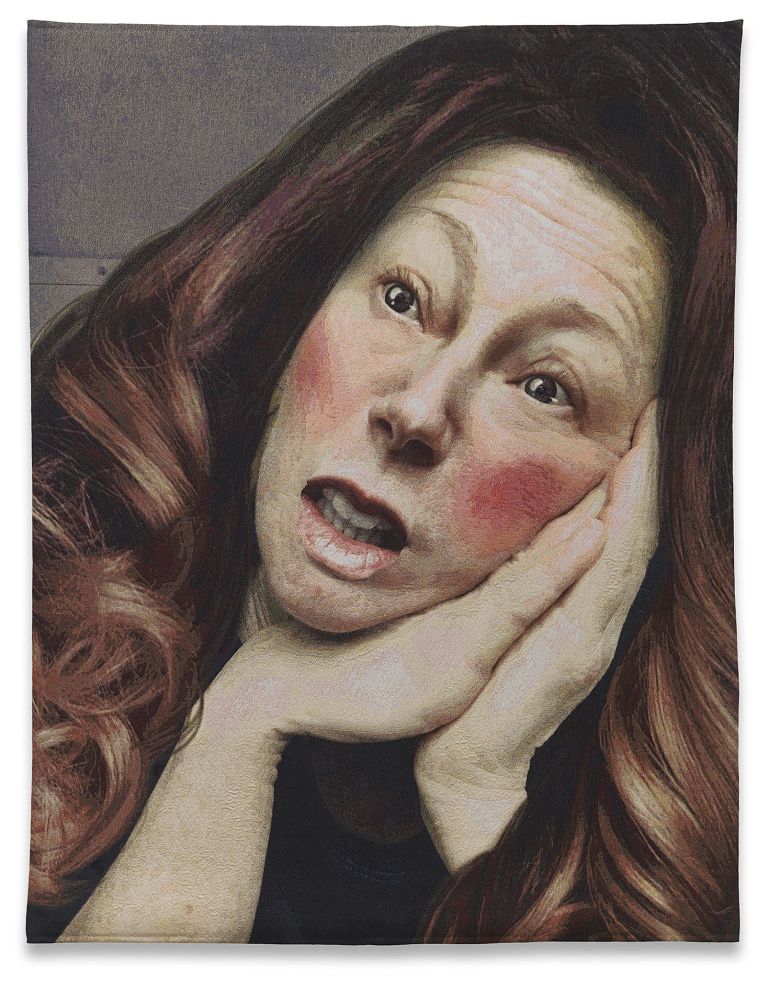

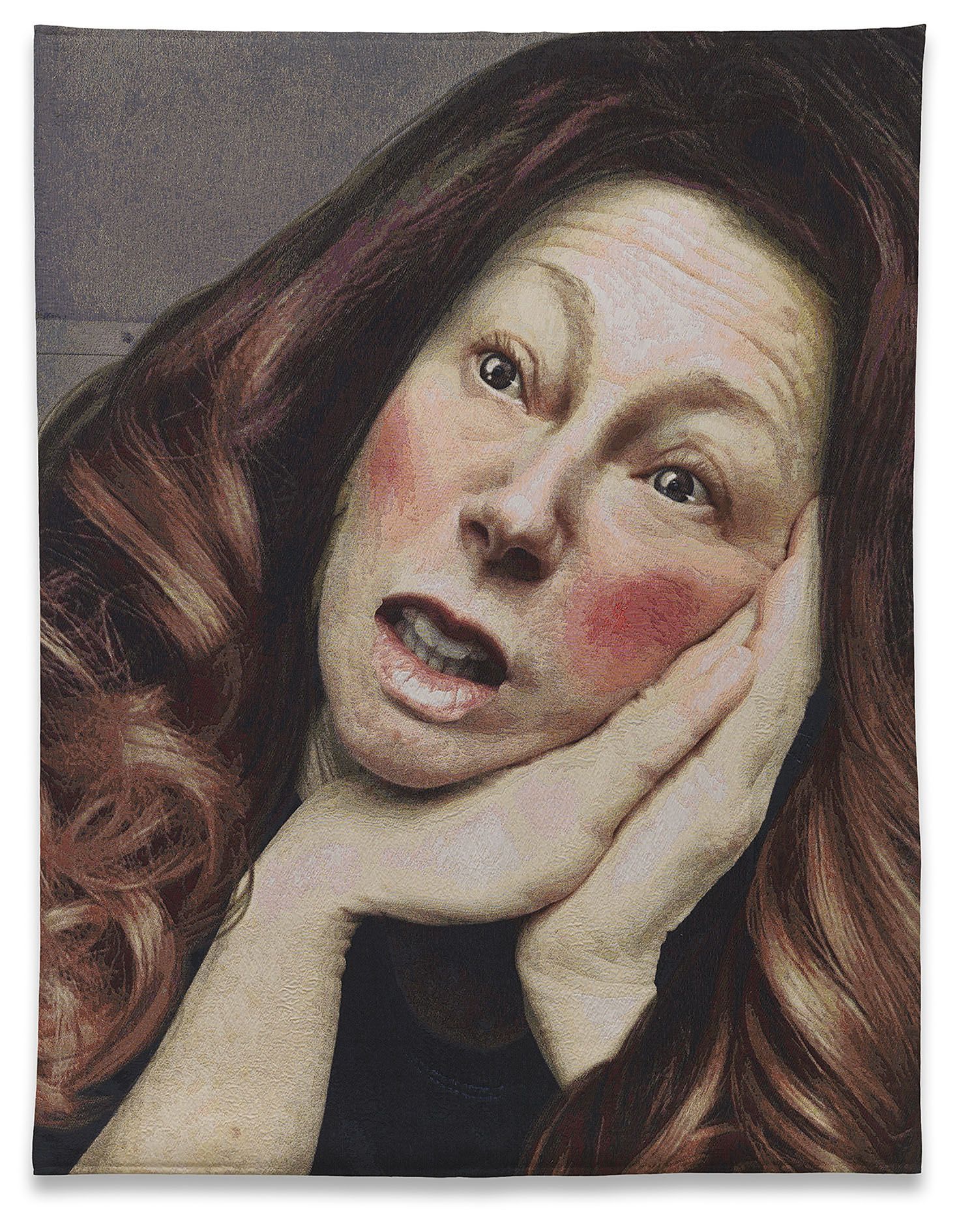

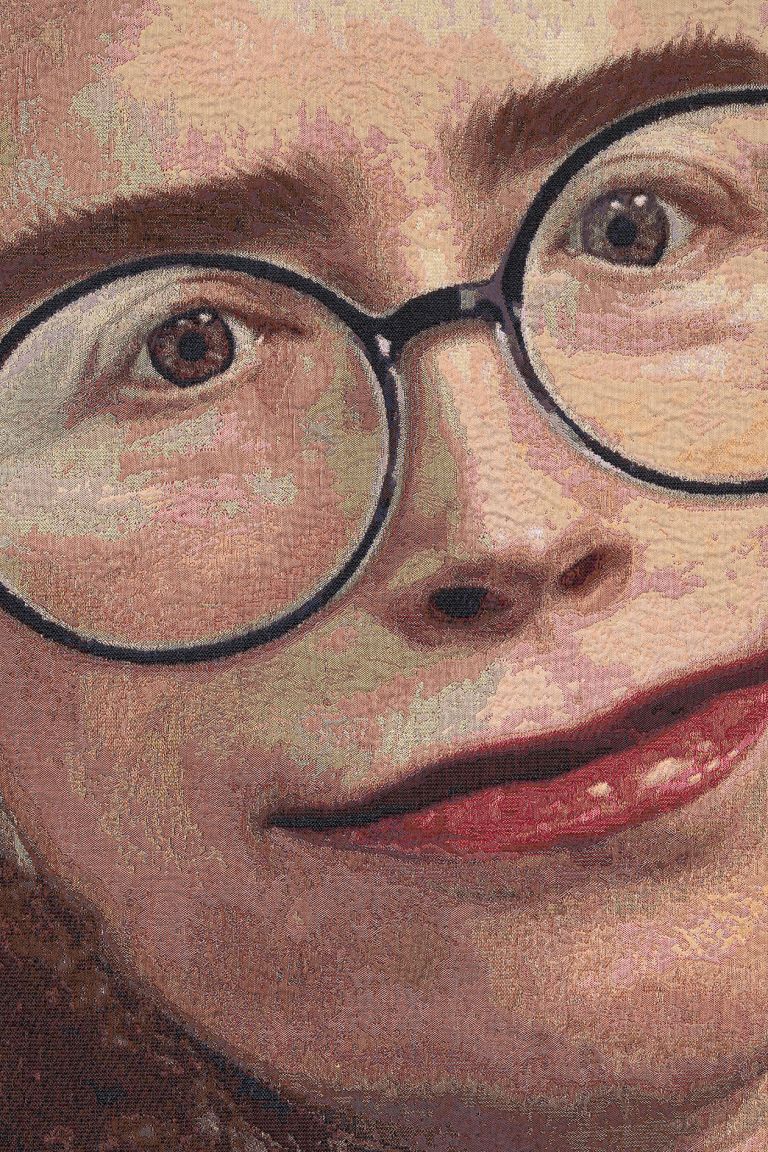

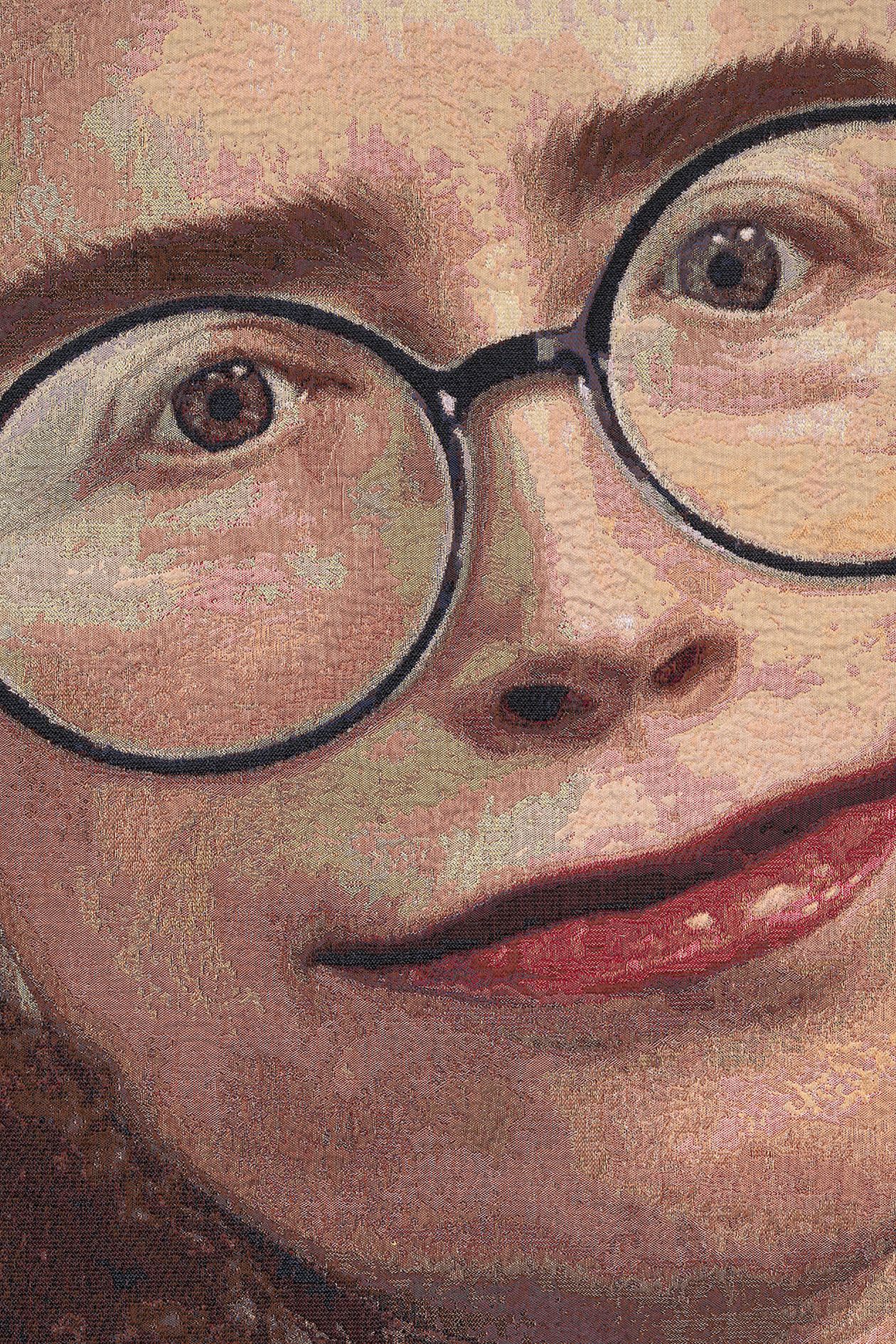

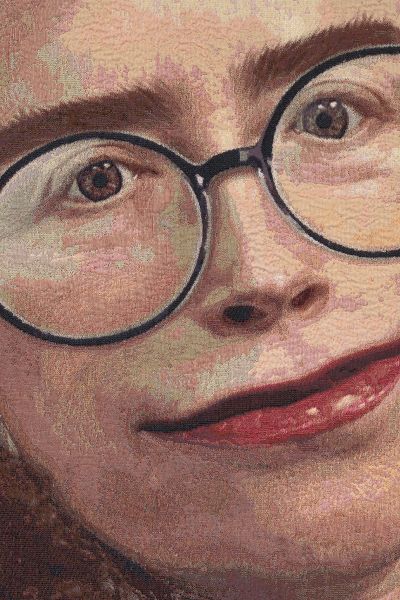

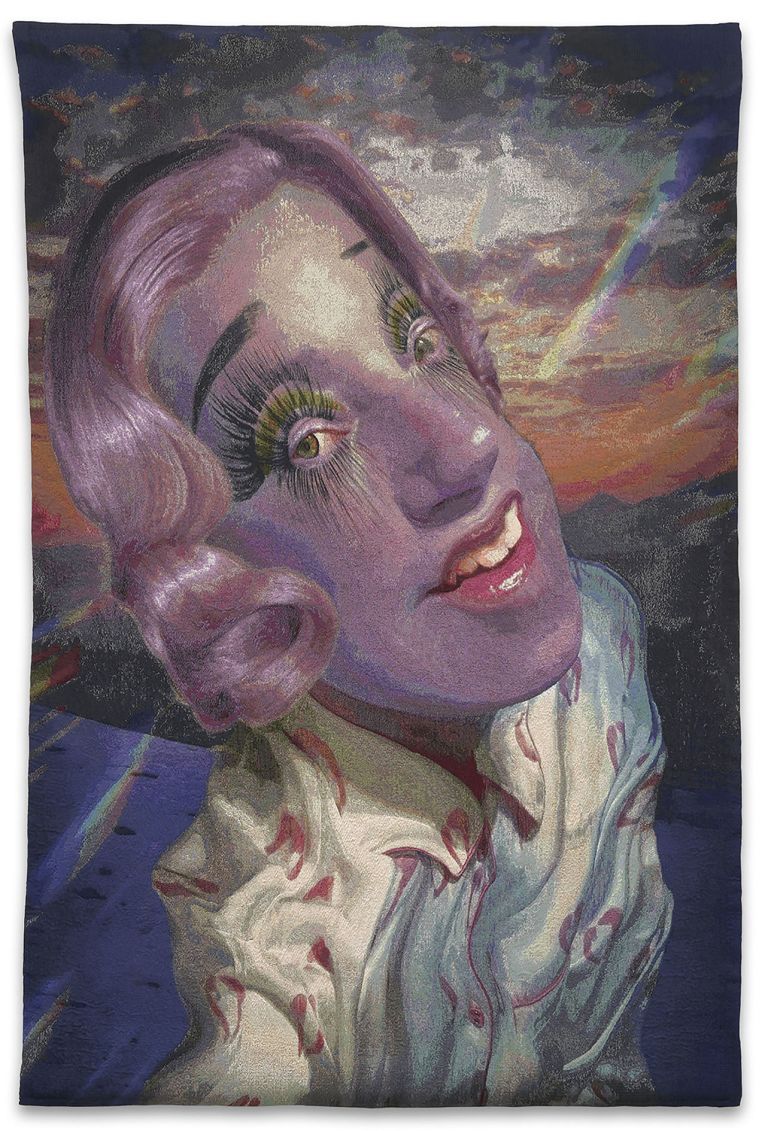

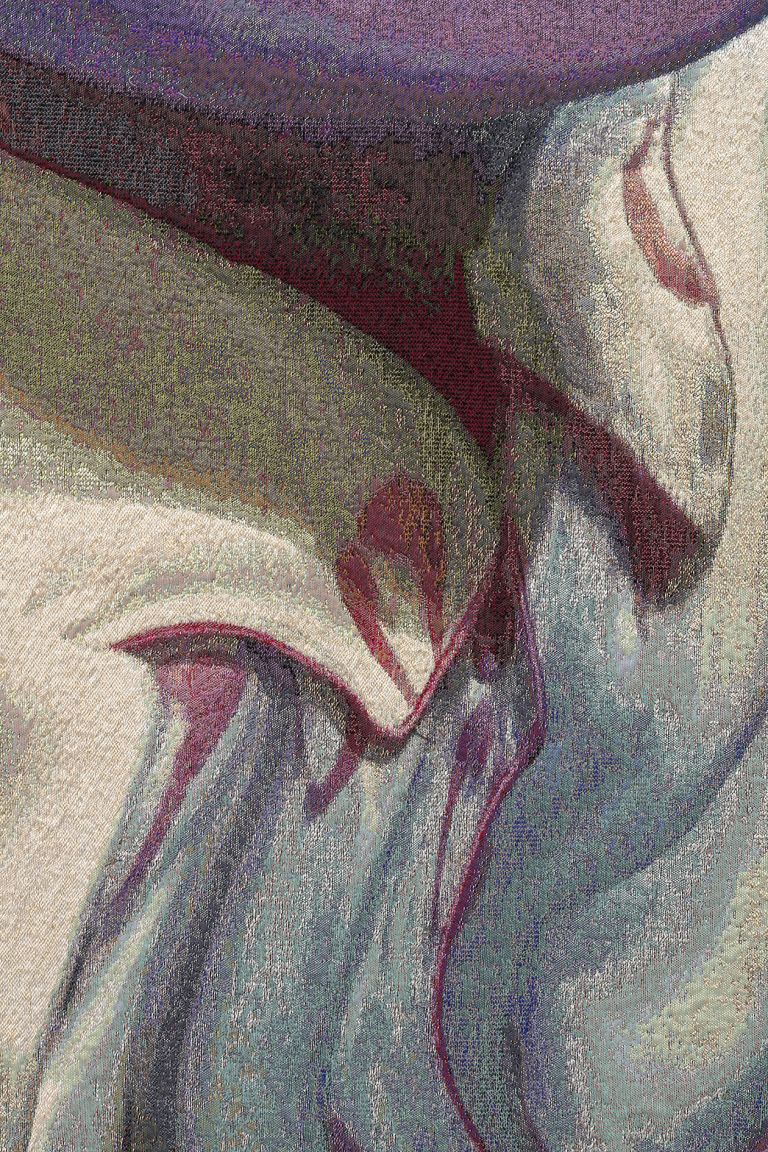

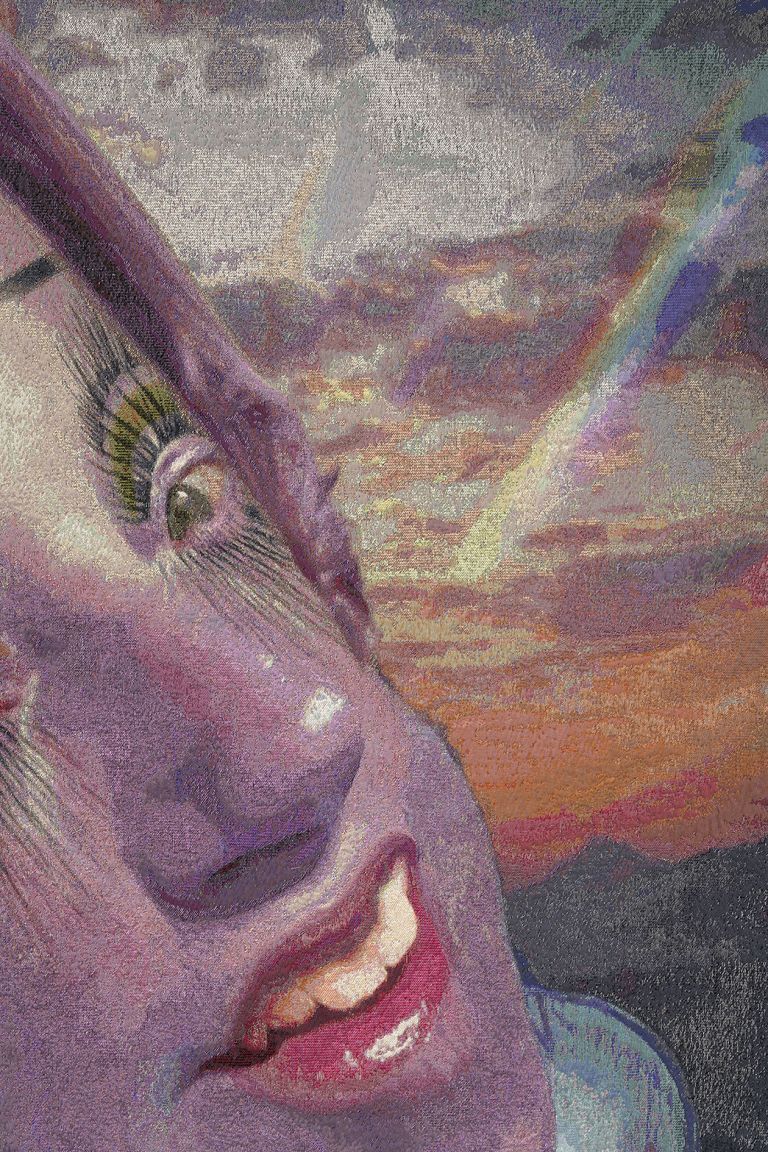

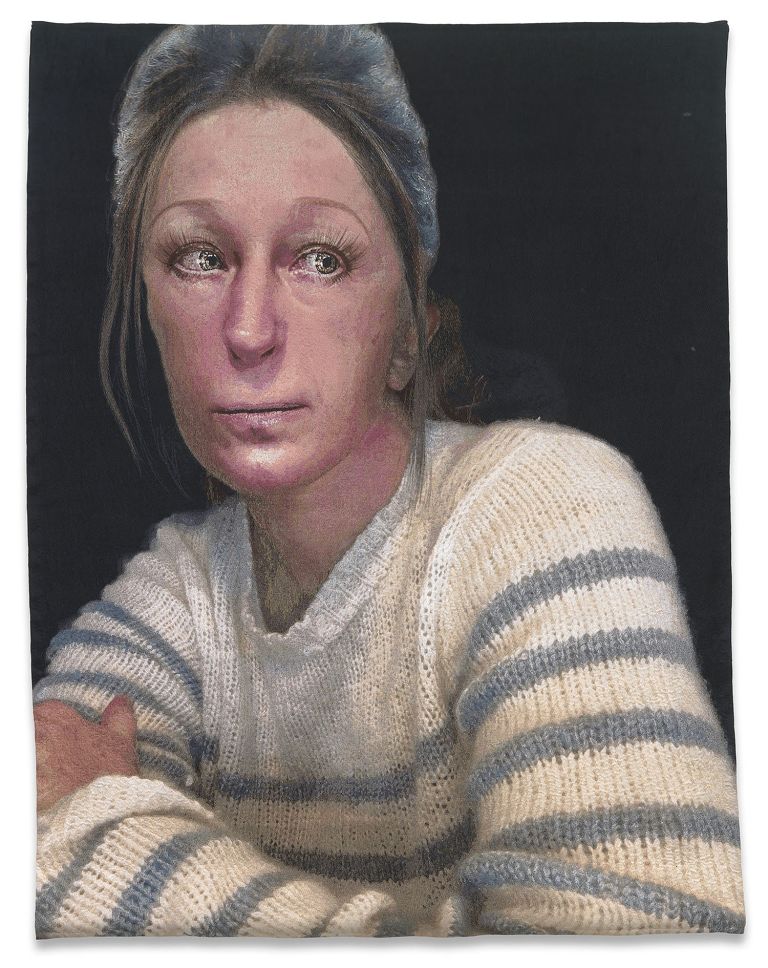

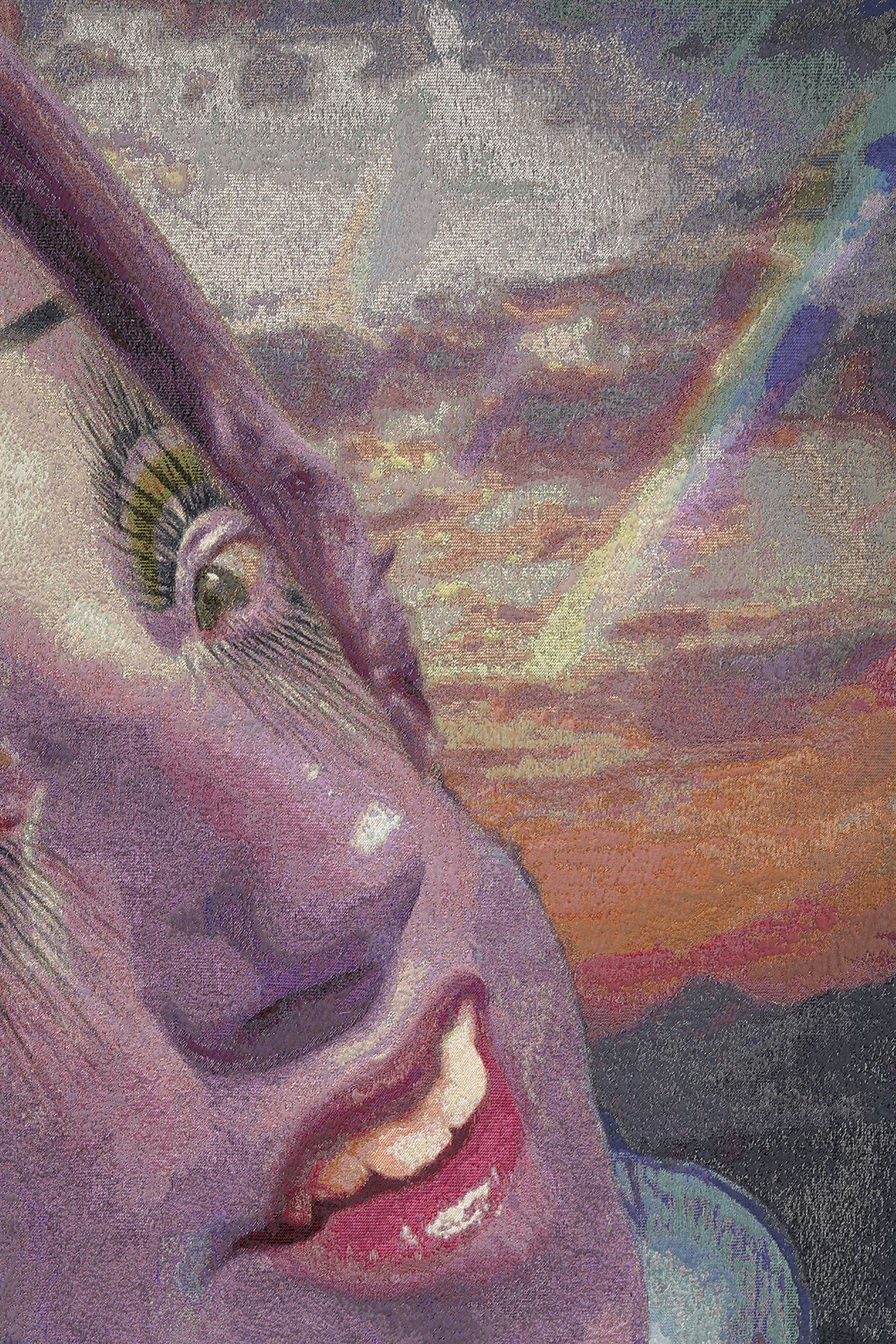

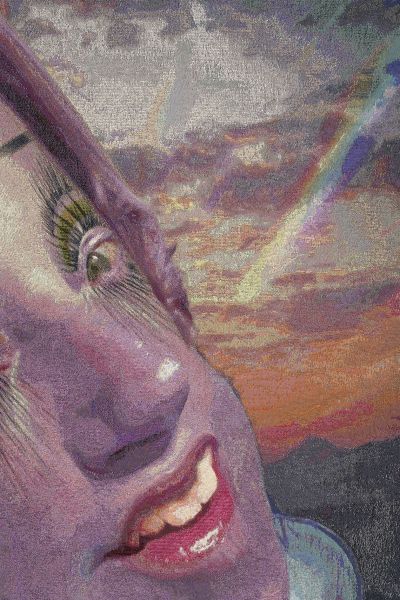

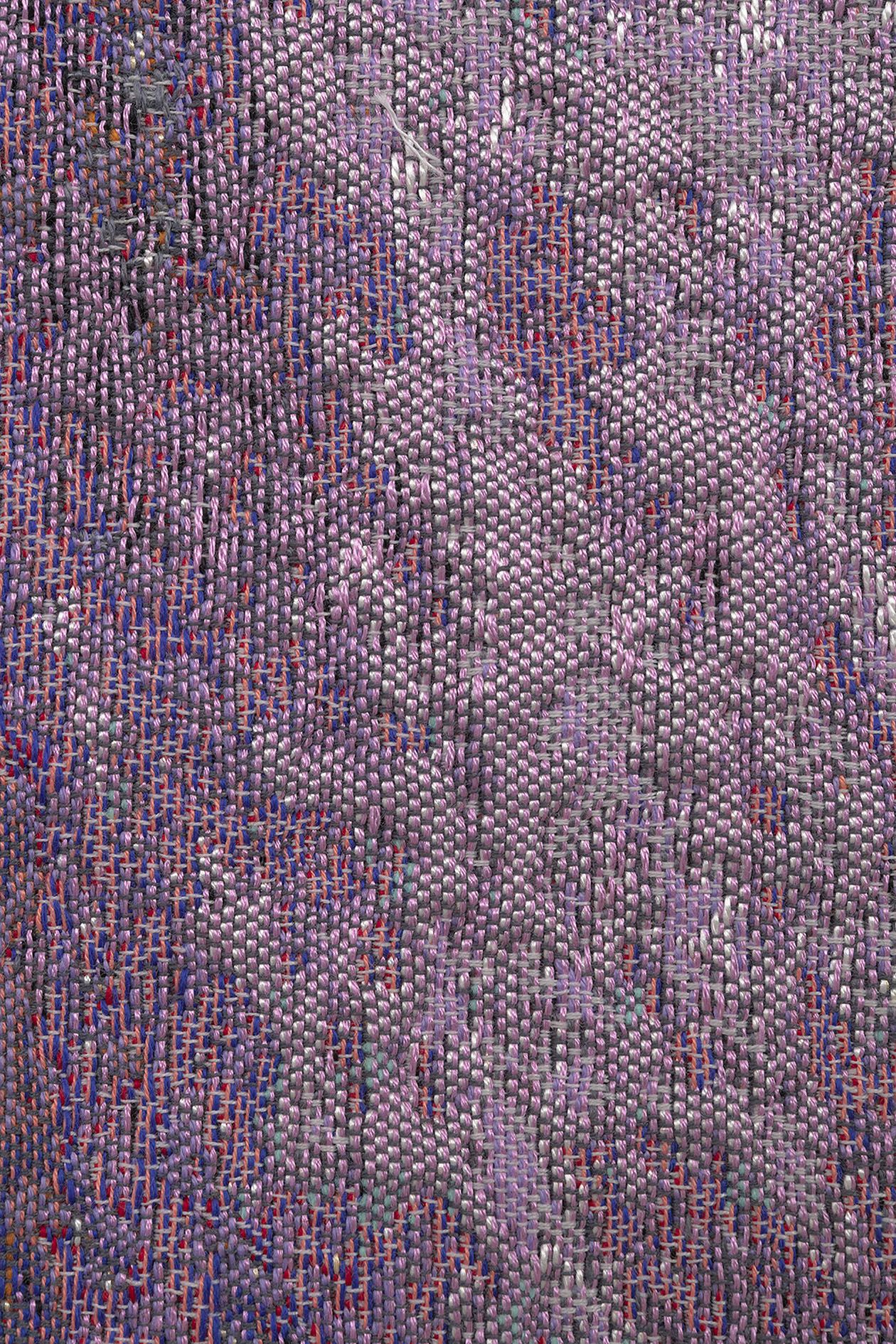

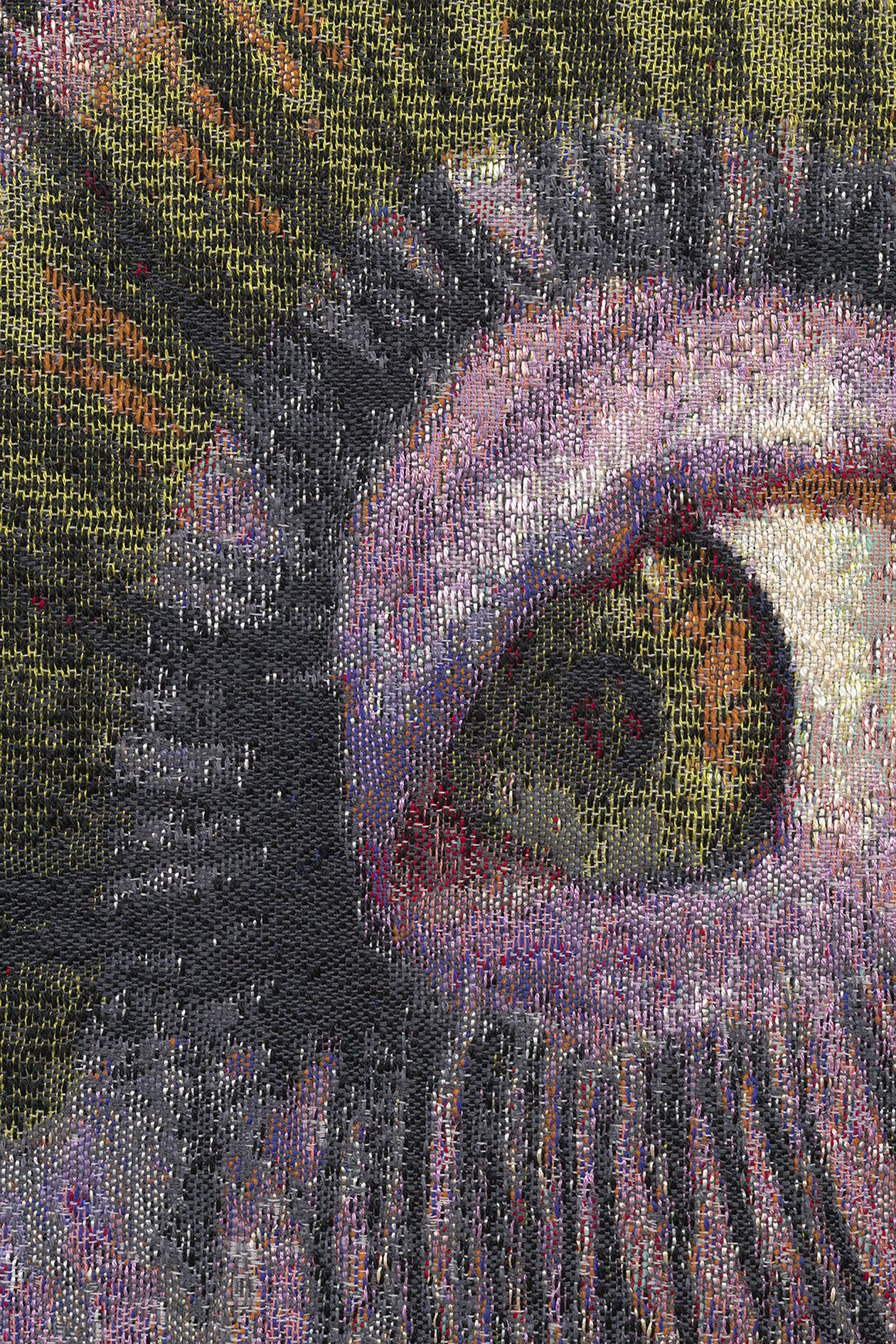

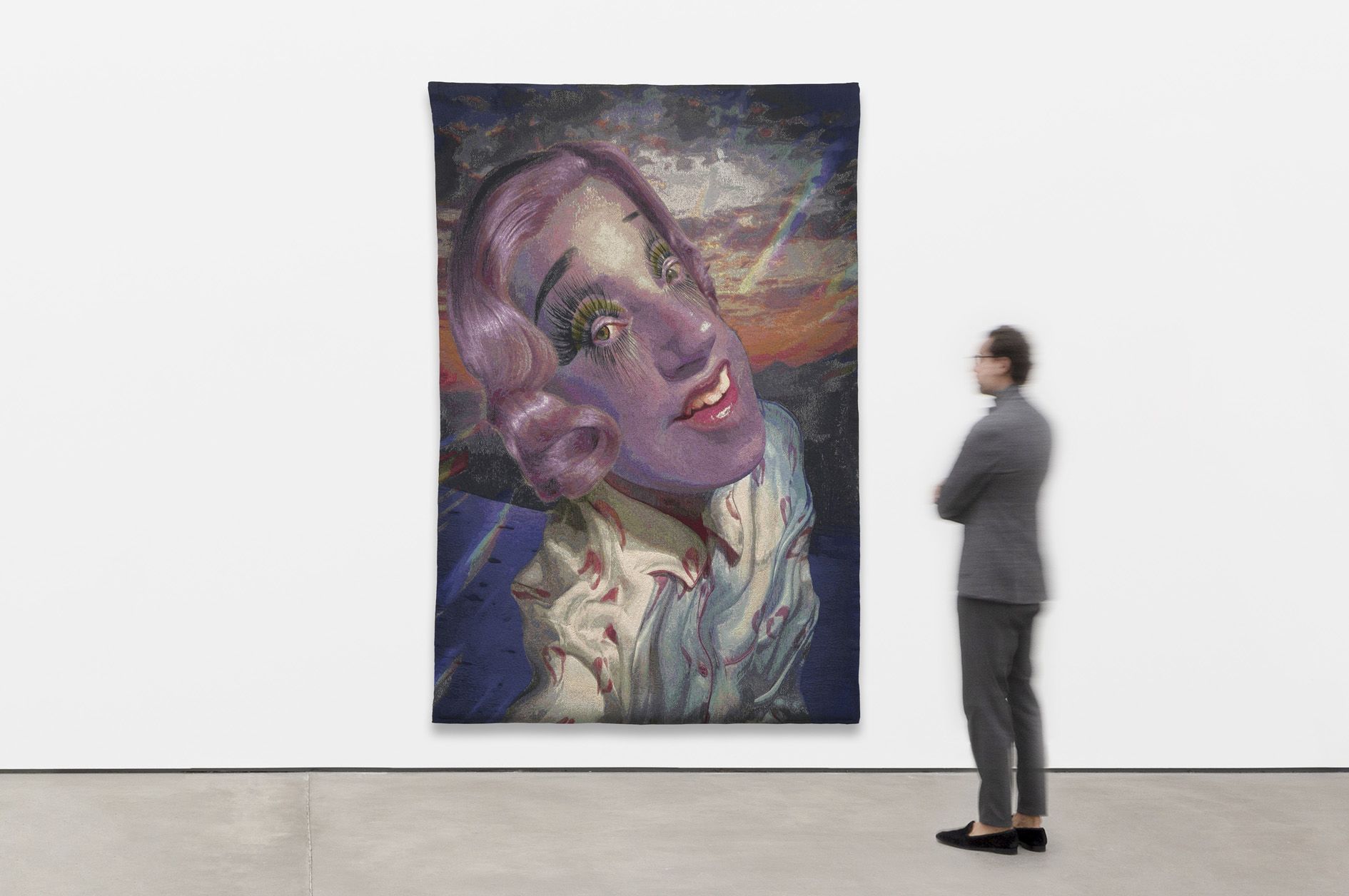

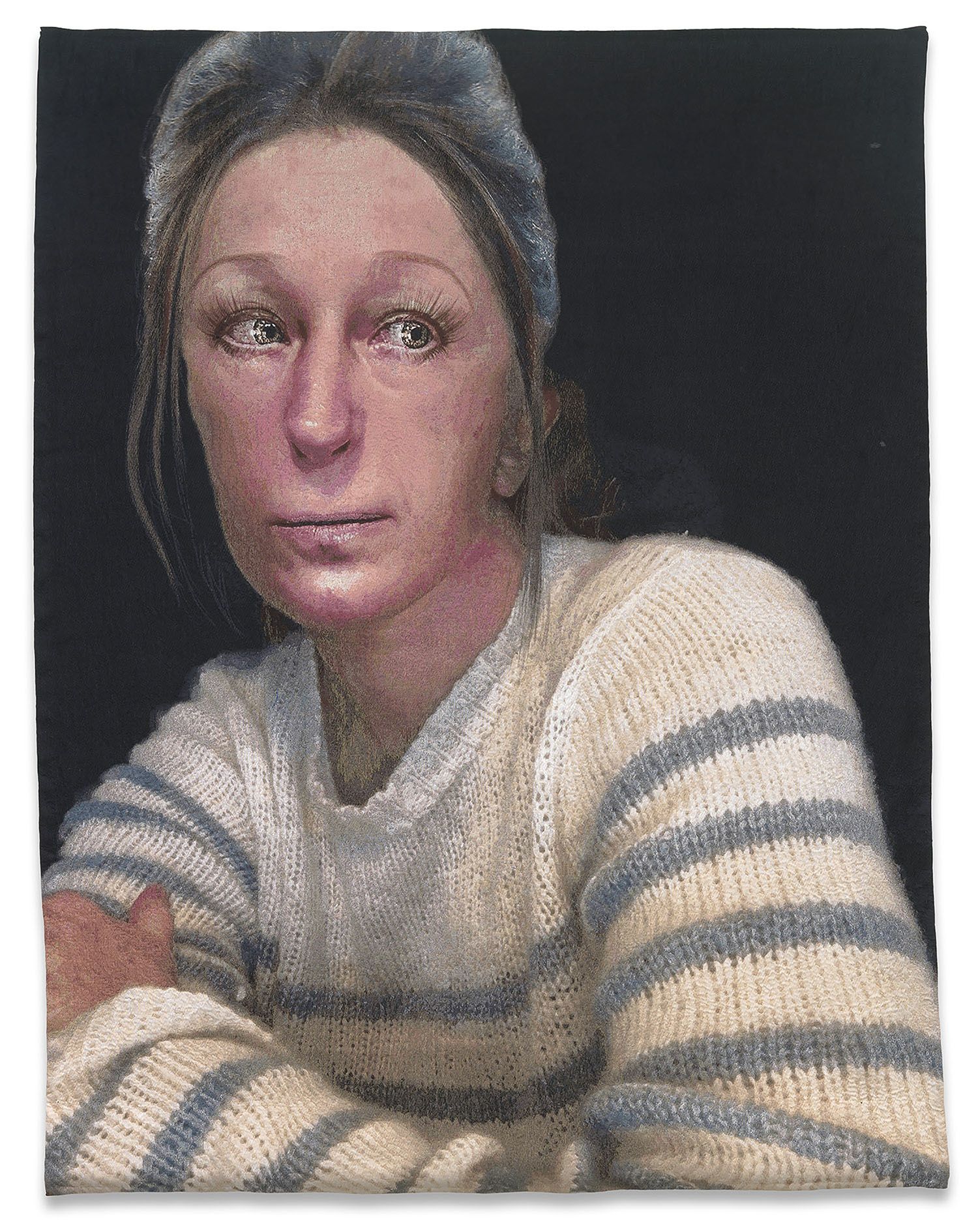

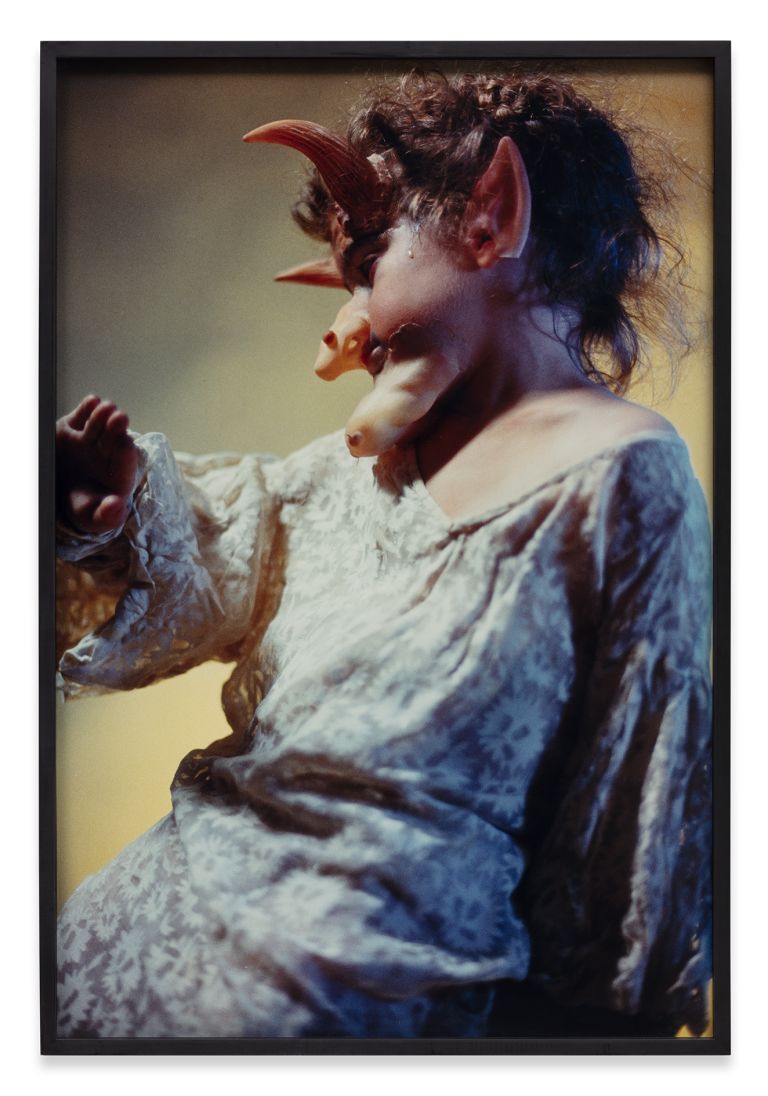

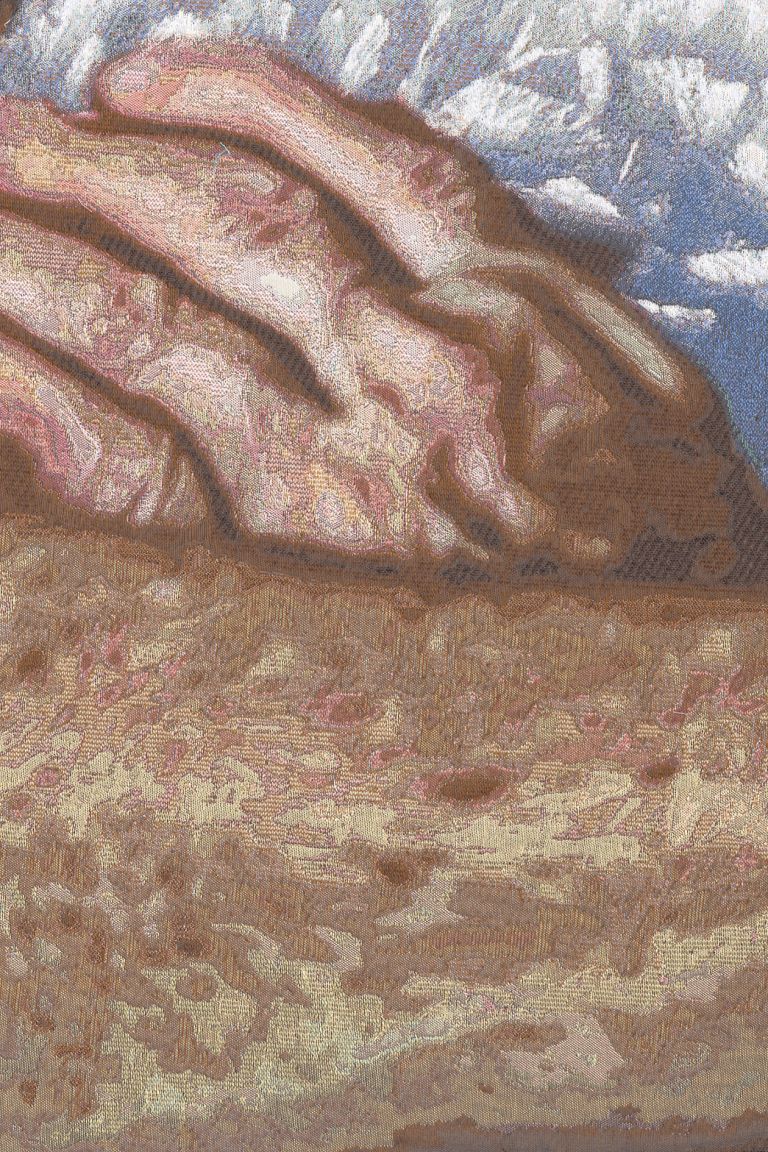

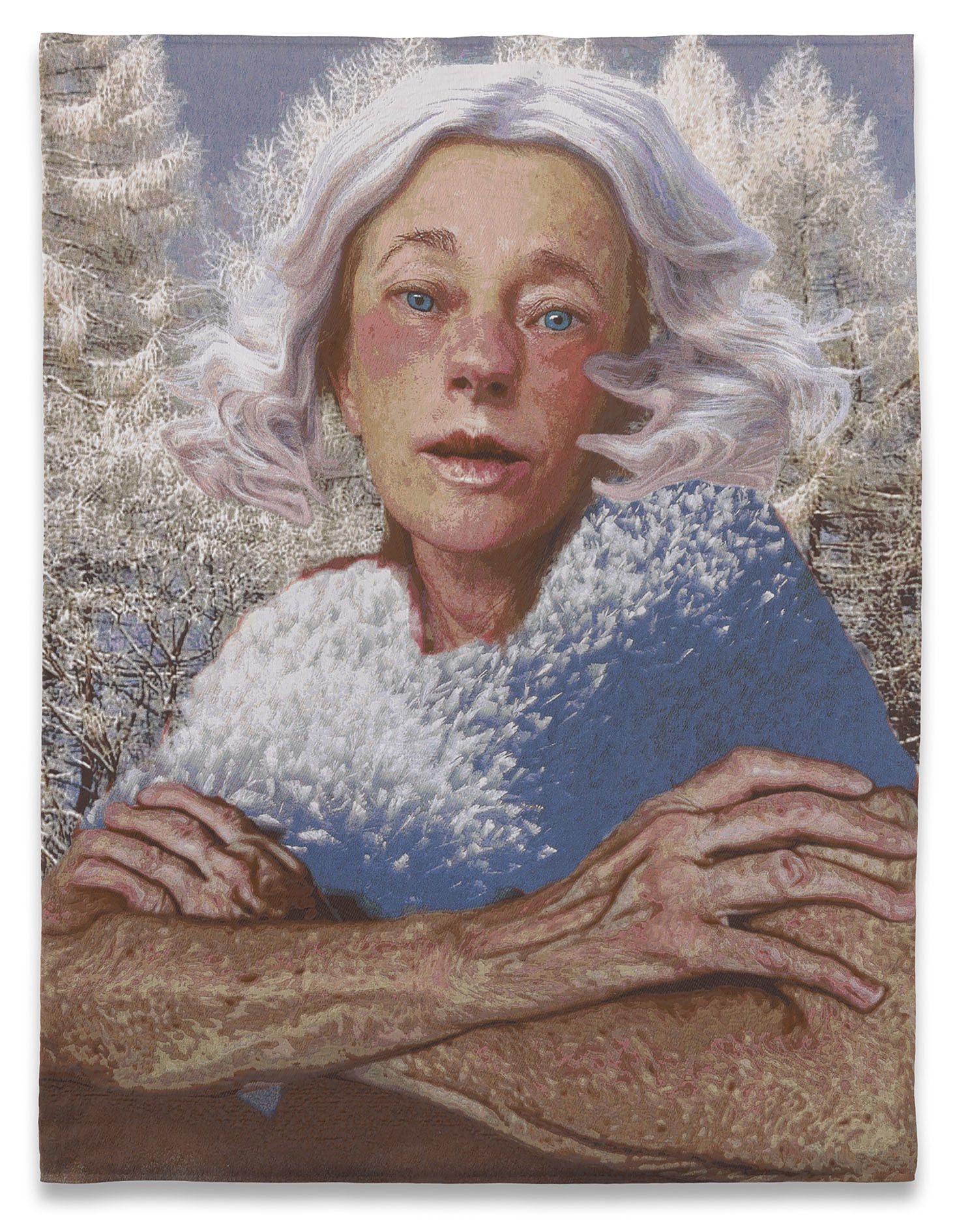

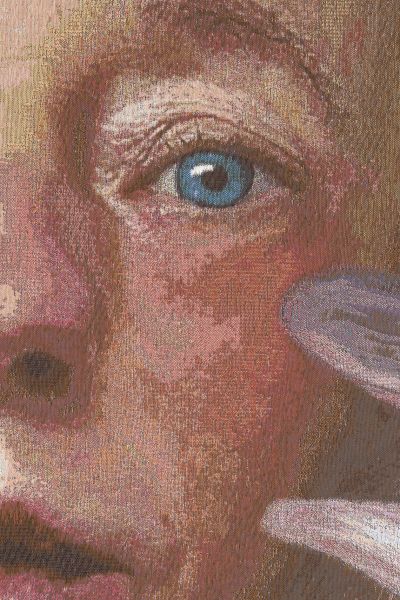

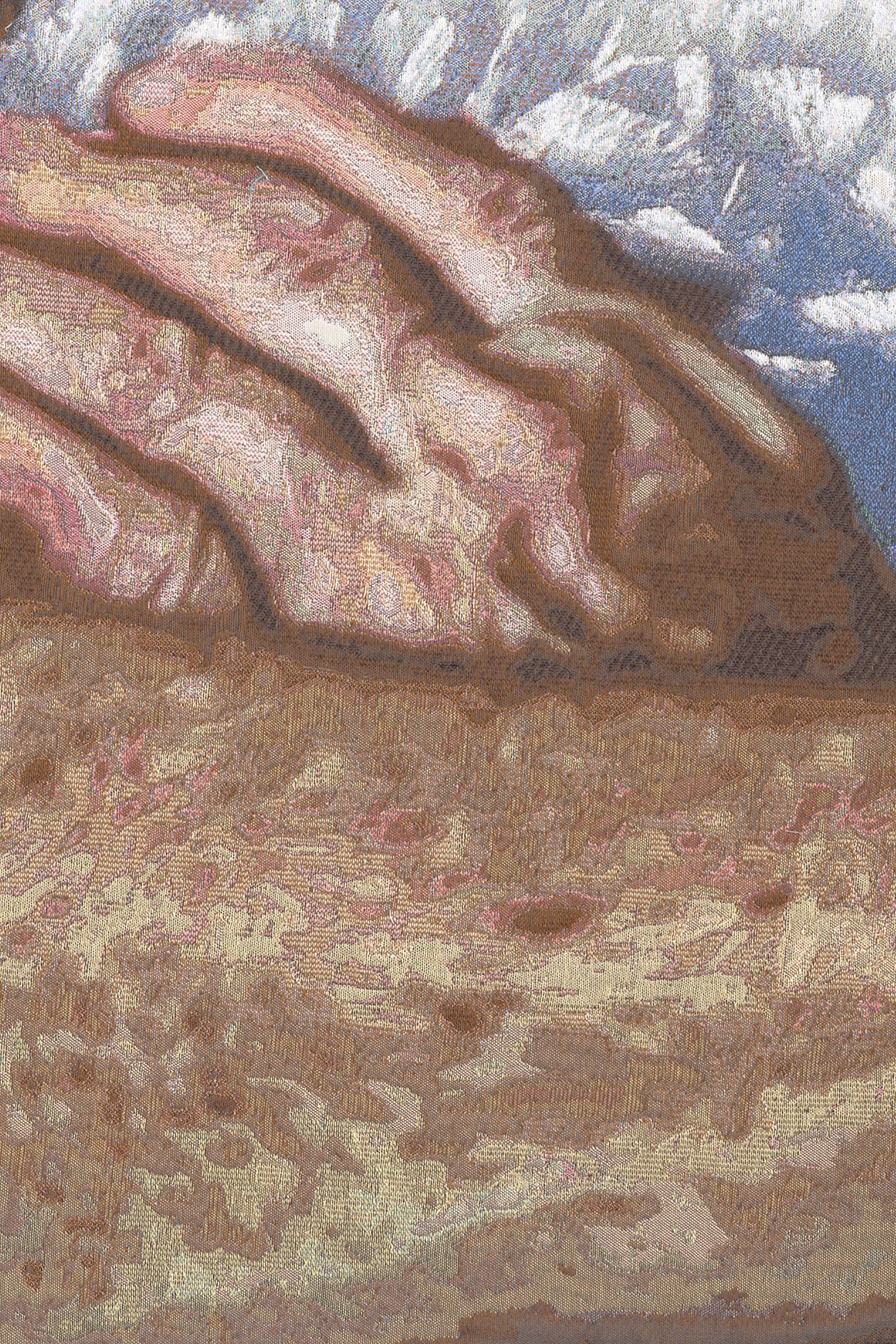

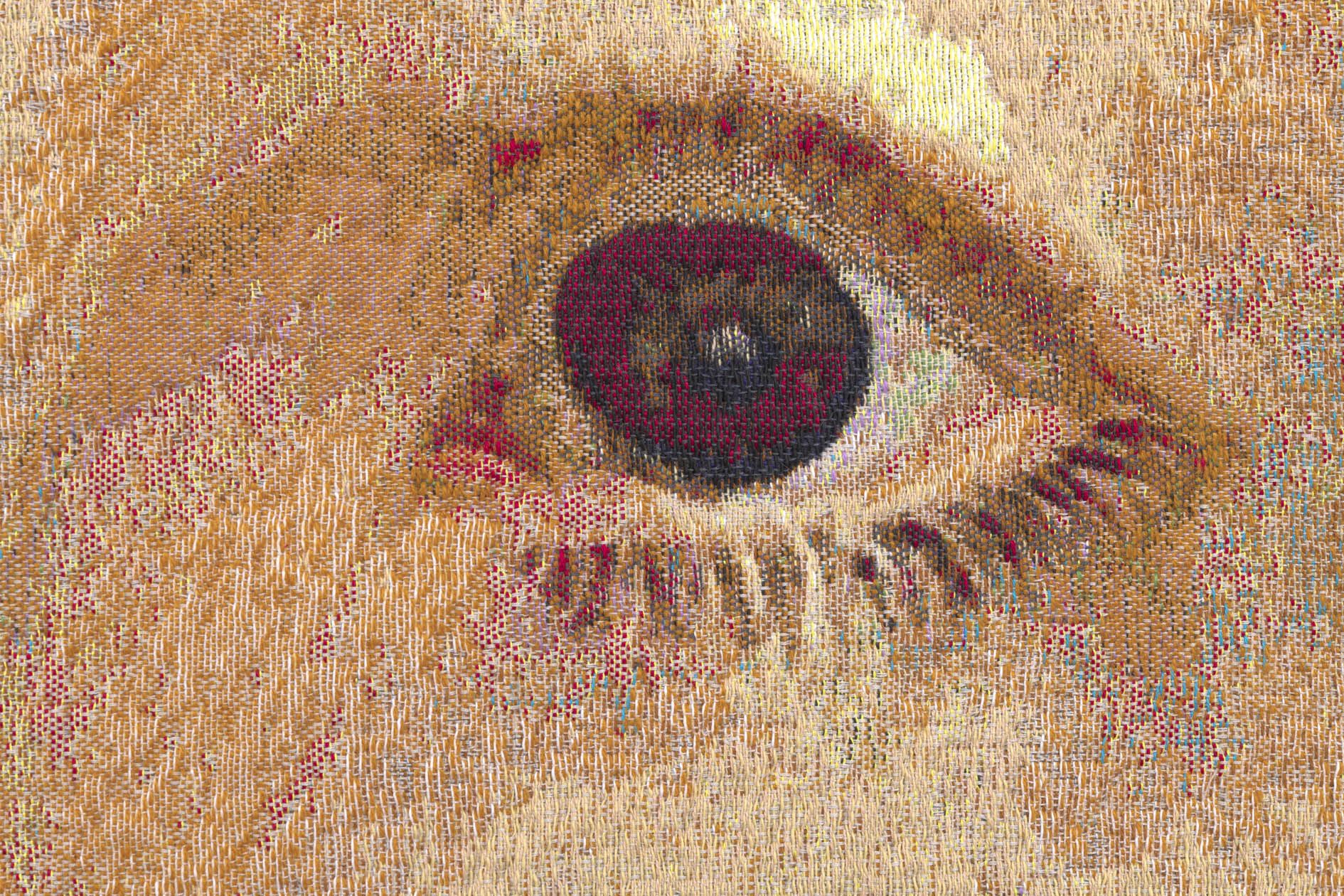

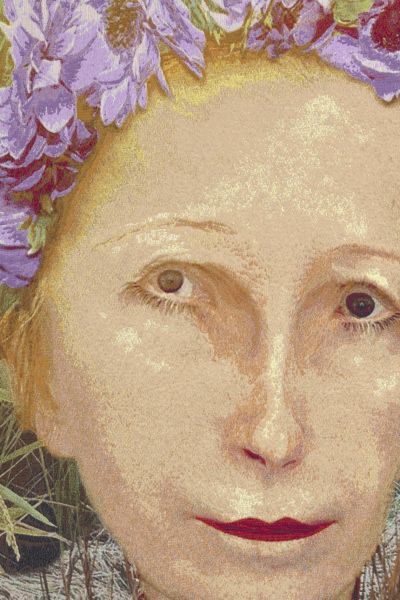

Sherman’s attention throughout her practice both to drama and to fashion connects the work to the long history of tapestry—a medium that in centuries past was valued even more highly than painting. Sherman’s works are produced in Flanders, which saw its golden age of tapestry beginning in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, when weavers developed new techniques that expanded their range of textures and visual effects, as well as the scale and intricacy of their compositions.

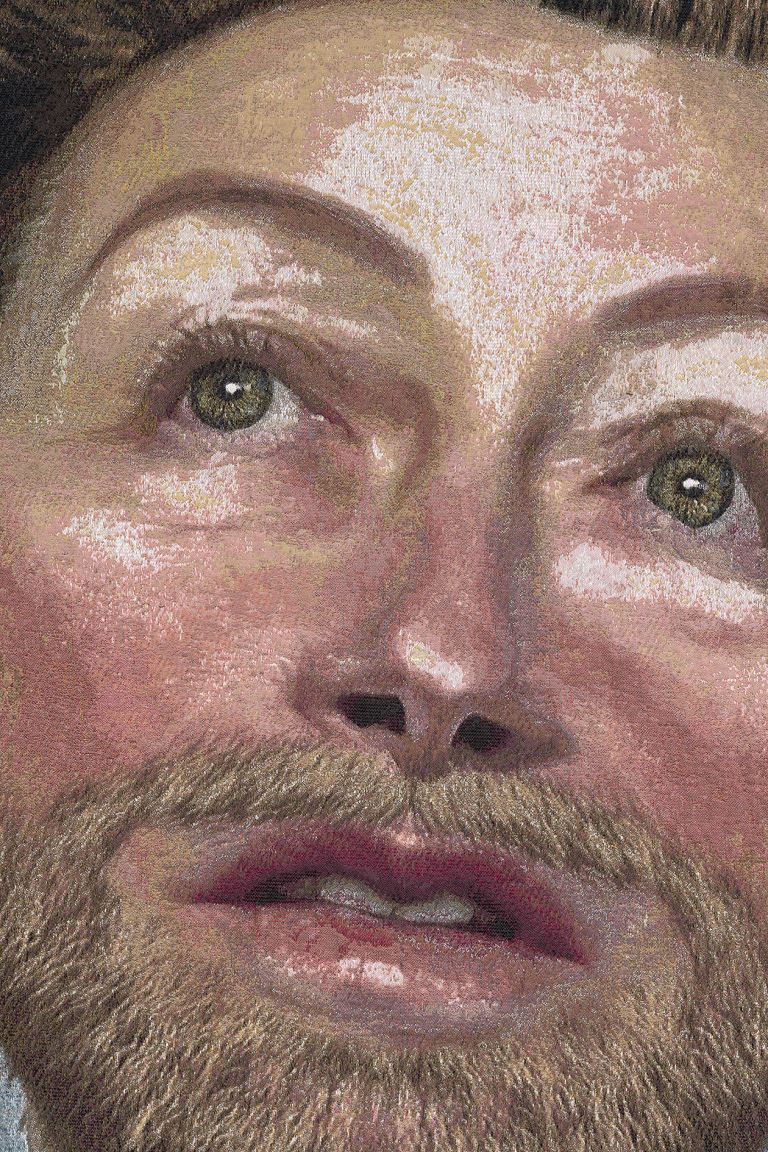

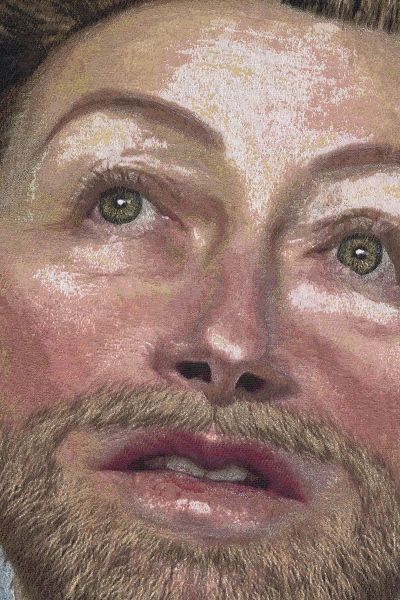

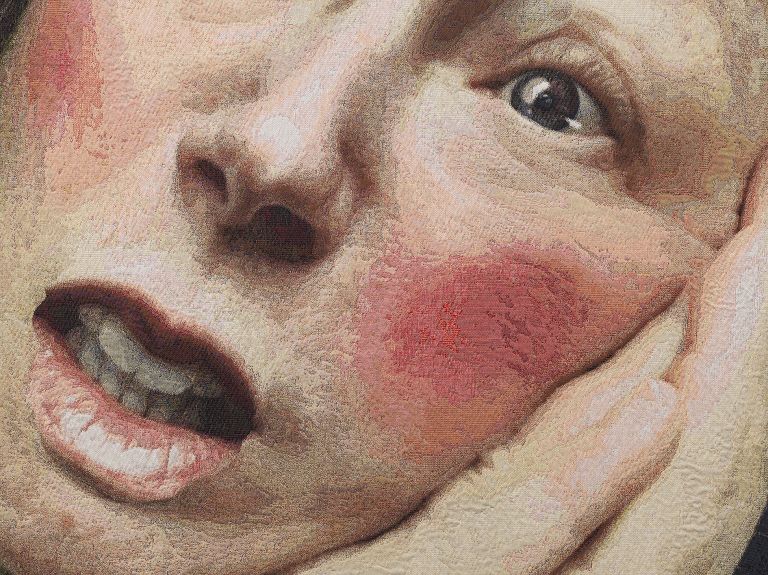

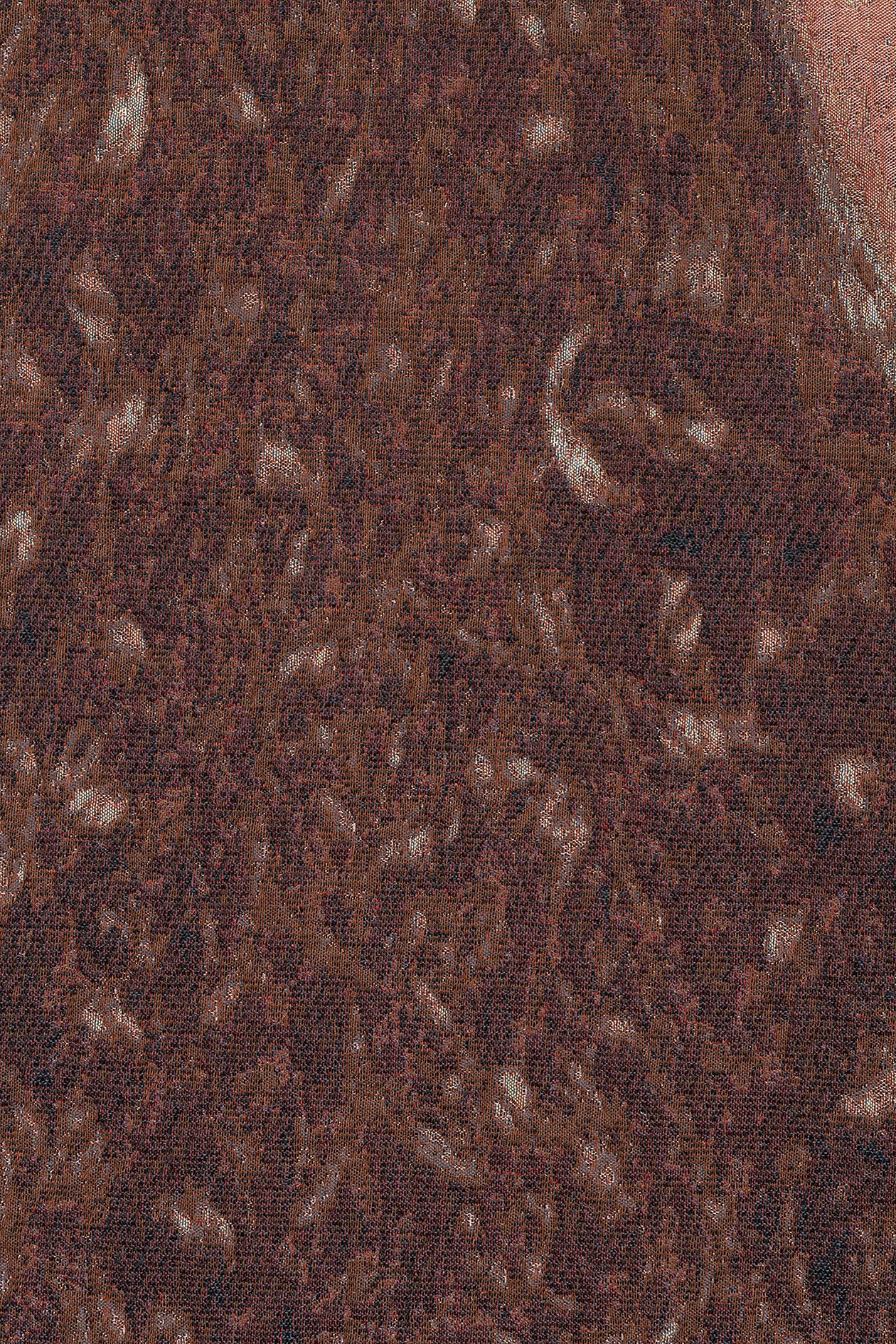

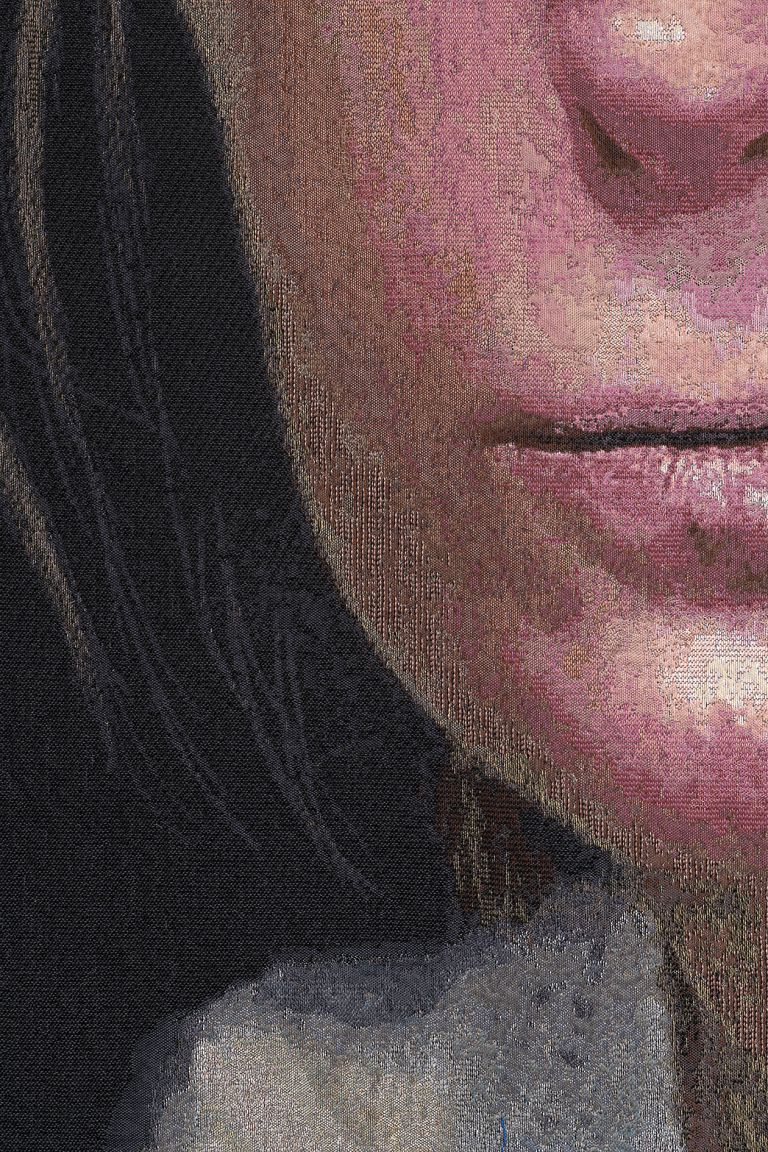

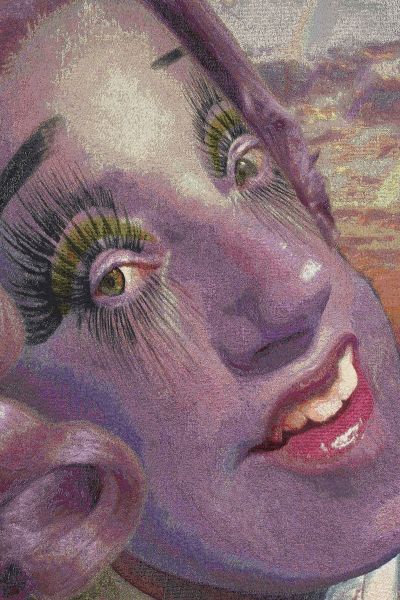

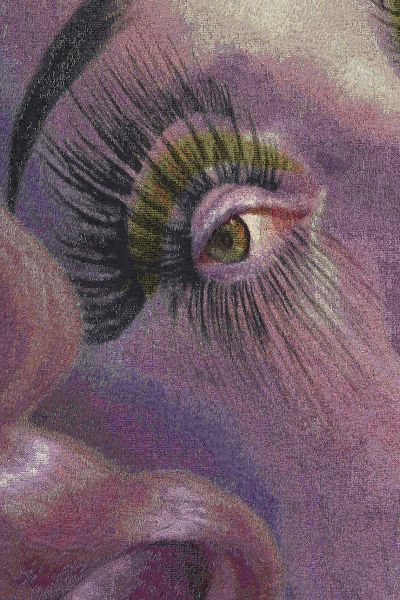

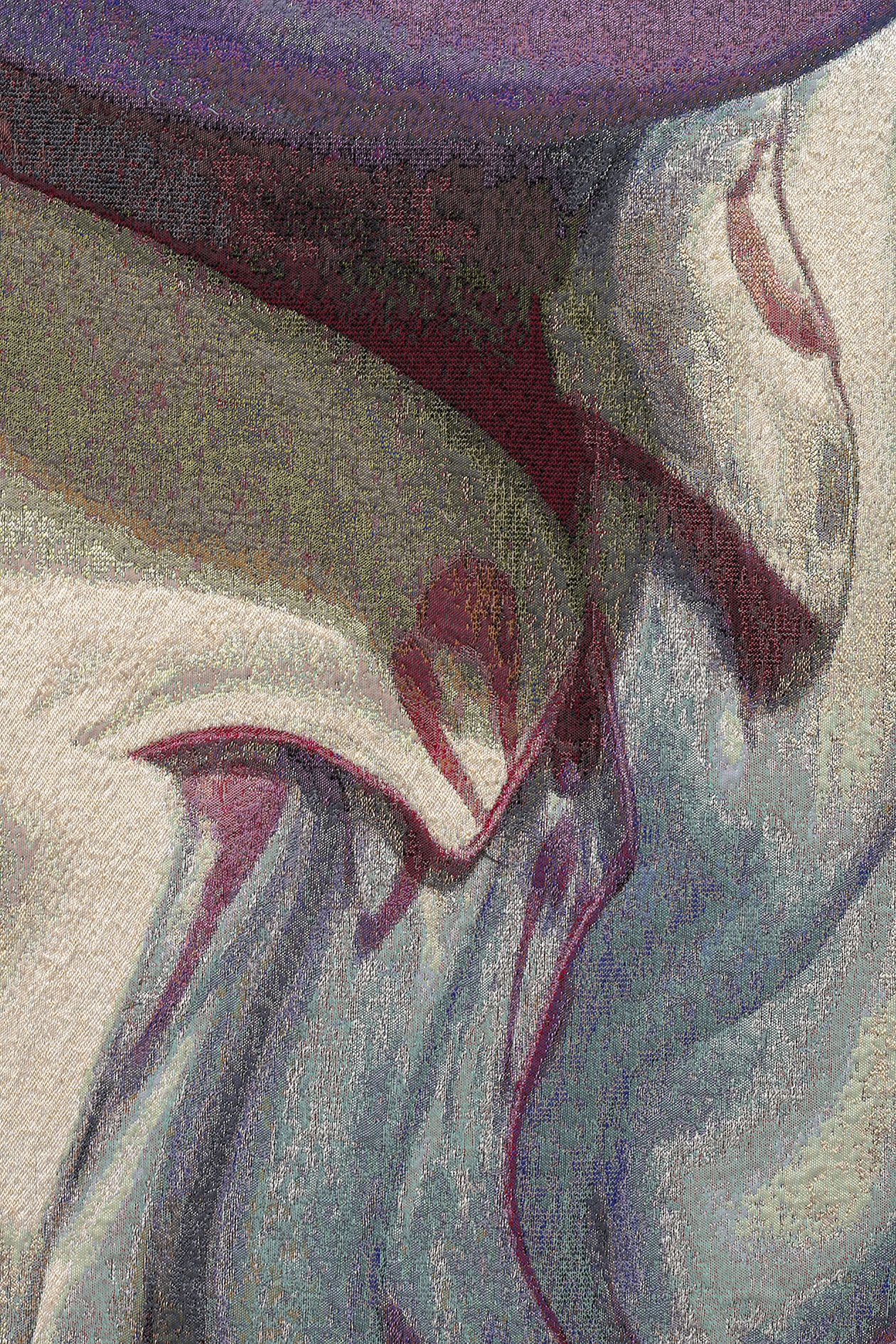

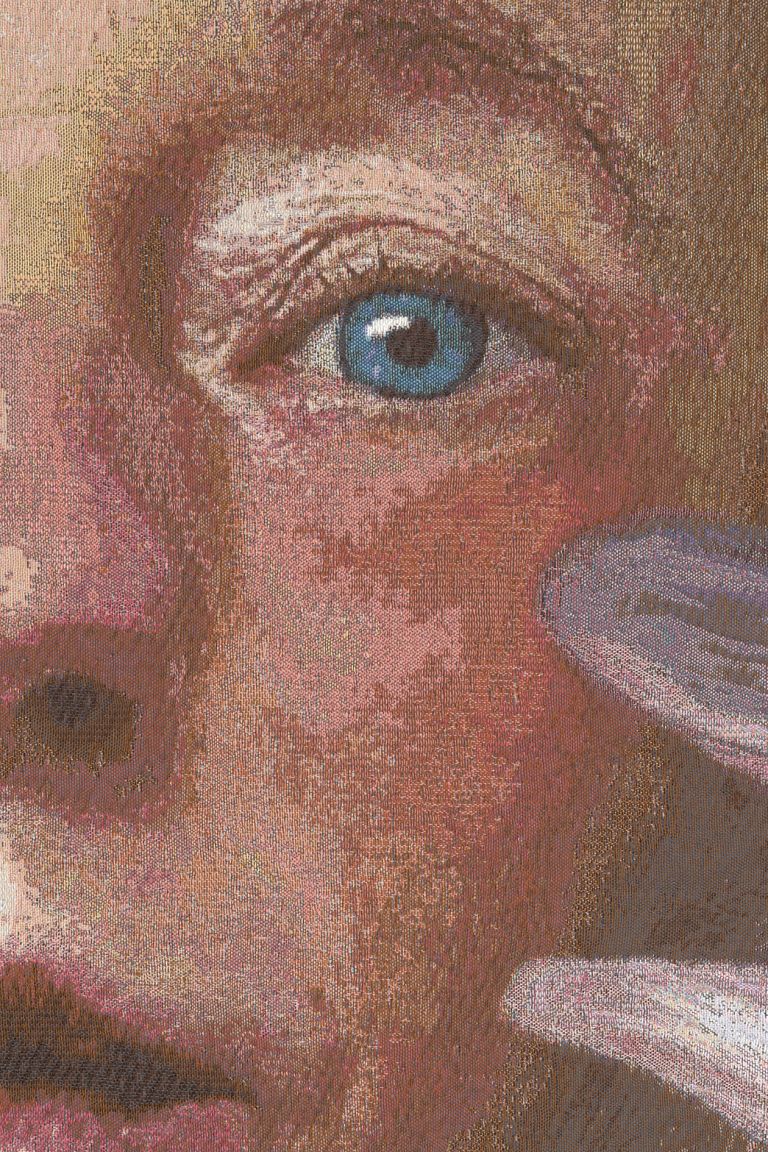

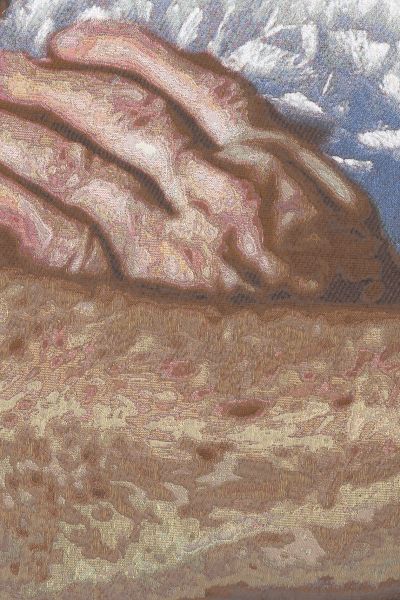

Sumptuous, and often woven with silk or gilded threads, tapestries connoted grandeur and wealth in the homes of those that could afford them. They also focused on evocative details such as setting, facial expressions and elegant fabrics and costumes.

Historically, each work began with a “cartoon” of the image to be woven; the workshop would then set to work transposing that image into thread. Sherman’s tapestries tap directly into this history: Instead of a hand-drawn or painted cartoon, she provides the digitally manipulated image straight from Instagram. Sherman’s tapestries also share the larger-than-life scale of these predecessors, and many include finer, more luxurious silken threads.