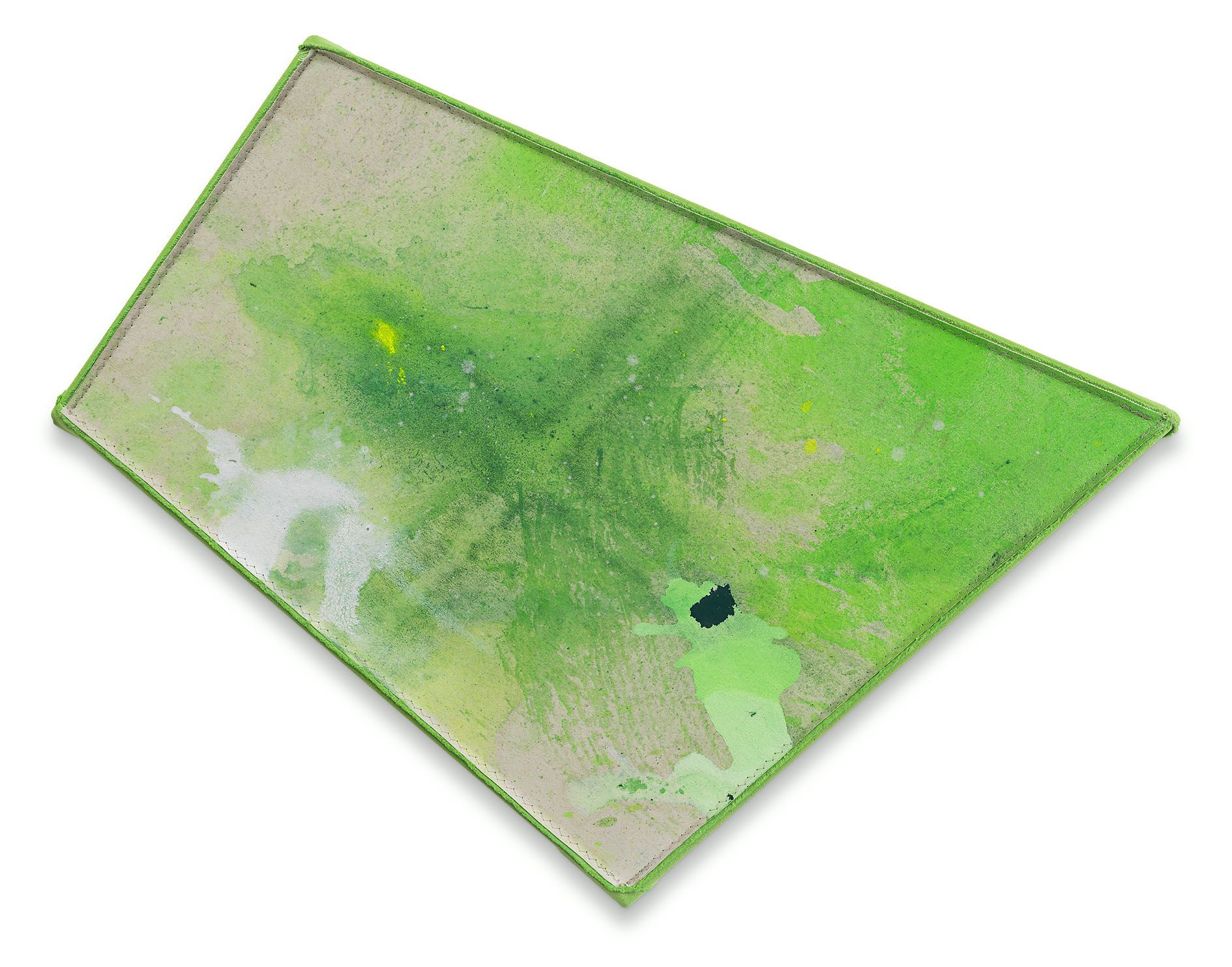

Louise Lawler, who ranks among the trailblazing female artists associated with the Pictures Generation, explores the presentation of artwork and the circumstances in which it is viewed. Her practice of photographing works of art, usually in situ at museums, auction houses or private homes, moves beyond documentation. Rather, it functions as a conceptual tool and way of directing attention to tacit and unspoken things—the constraints, rules, and economies of the loose system that governs the art world. In Lawler’s aptly named series Three Sizes in Twelve Colors (1994/2019), the artist revisits one of her earlier images, It Could Be Elvis (1994), by transferring it to different formats and colors. Each size (S/M/L) has twelve variants that each, in turn, shifts in hue, thereby covering the full spectrum of the color wheel. A vital aspect of Lawler’s process, the continuous re-presentation and recontextualization of existing images, demonstrates the discerning and relational character of her art.