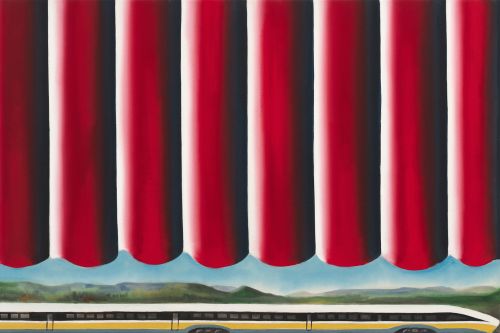

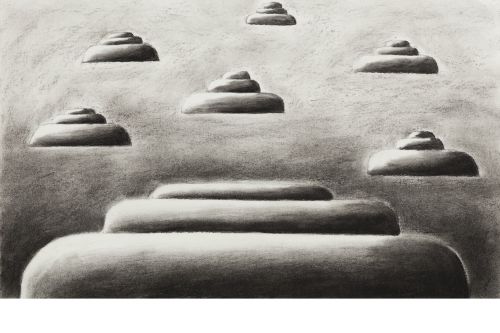

Andreas Schulze (*1955) is one of the great individualists of German painting. The artist’s unique painting style defamiliarizes basic design and architectural forms, with a cryptic pictorial repertoire that oscillates between gentle irony and friendly affirmation, menace and comfort. It exposes the blind spots of middle-class life and ironizes the pretensions of contemporary art. The Cologne-based artist has been associated with the gallery since 1983.

Photo: Oriol Tarridas

Andreas Schulze

Special

Institute of Contemporary Art – ICA, Miami

Through March 15, 2026

Featuring paintings and sculptures from 1982 to the present, Special is the first solo museum exhibition in the United States for the German painter Andreas Schulze. Though never formally part of any movement or group, Schulze first emerged in 1980s Cologne during the rise of neo-expressionism, forming a singular practice to depict everyday life while challenging the conventions of abstraction and figurative representation. The exhibition surveys the range of Schulze’s distinctive visual language, which features tableaux rich with absurdist humor. Schulze’s imaginative studies of the objects around him are enlivened as their surfaces and volumes take on exaggerated gradients, evoking studio lighting and memory, as well as the dream worlds of surrealism and the gleaming surfaces of pop art.

Learn more