The films, videos, photos, digital projects, drawings and complex multimedia installations of Cao Fei (*1978) explore far-reaching social changes in our era of globalization, urbanization and digitalization. The Beijing-based artist’s oeuvre sheds light on the ways people react to these developments and integrate them into their lives. Operating as both artistic invention and social documentation, the visual language of her work verges on the fantastic, with a melancholy atmosphere leavened by moments of humor and surreal beauty.

Mondi Possibili

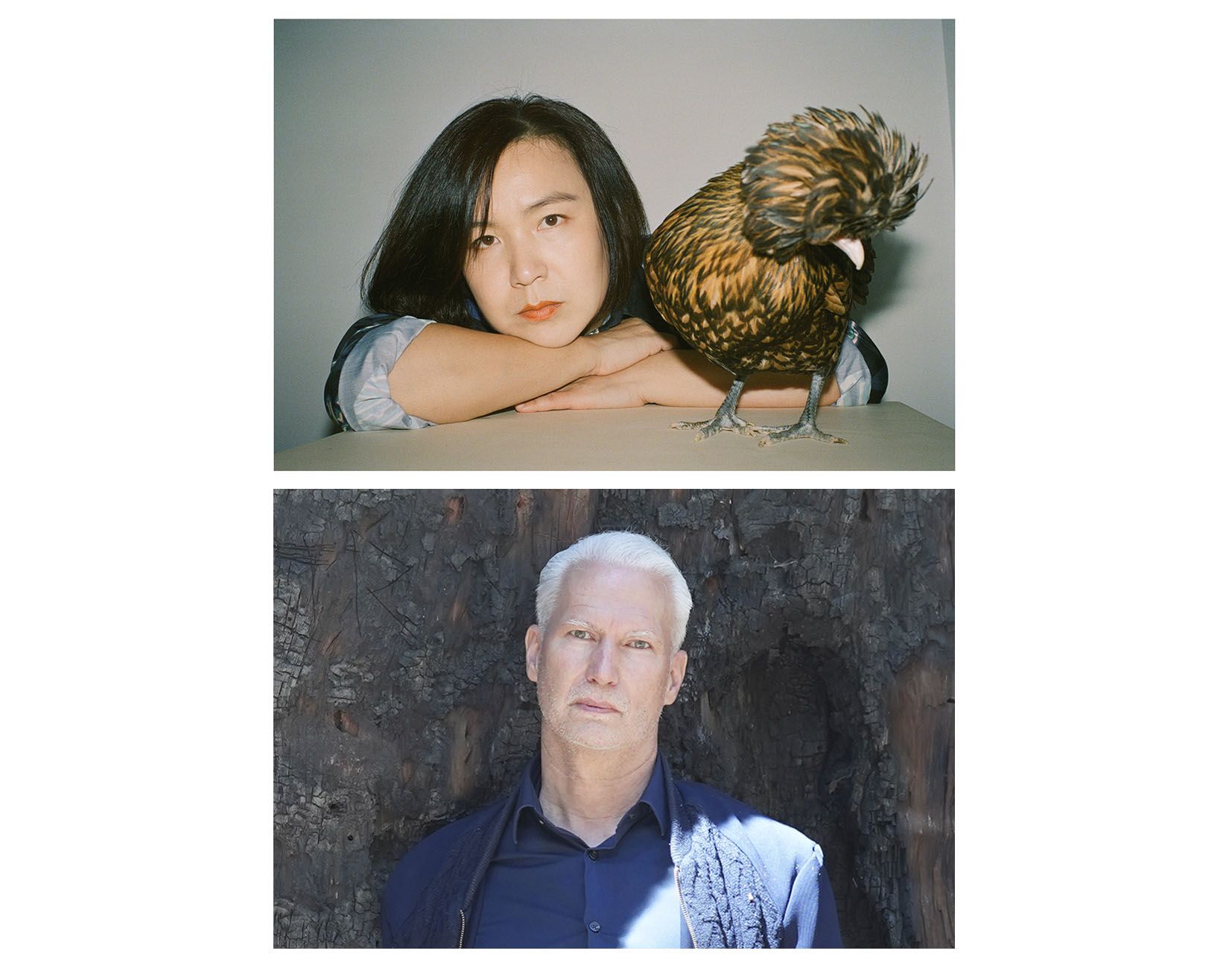

Henni Alftan, John Baldessari, Cao Fei, Thomas Demand, Thea Djordjadze, Lucy Dodd, Robert Elfgen, Peter Fischli David Weiss, Sylvie Fleury, Jenny Holzer, Donald Judd, Karen Kilimnik, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, David Ostrowski, Michail Pirgelis, Sterling Ruby, Thomas Scheibitz, Andreas Schulze, Hyun-Sook Song, Robert Therrien, Rosemarie Trockel, Kaari Upson, Andrea Zittel

August 31–September 14, 2023

Seoul

Mondi Possibili highlights the interplay between art and design and explores the many ways in which experimentation with material, technique and scale can reveal the hidden narratives, quiet drama and humor in the everyday items that furnish our lives as well as our imaginations. Connected through a paradigm of the possible, all artworks on show examine familiar objects – citing, celebrating, adapting or appropriating them – offering surprising, playful or unsettling approaches that open up a range of “possible worlds.” This will be the fourth edition of Sprüth Magers’ Mondi Possibili – first titled by Pasquale Leccese – showcasing significant themes in the selected artists’ works as well as the gallery’s longstanding heritage. Its three previous iterations were presented in 1989, 2006 and 2007 in Cologne, where the gallery’s history is firmly rooted, and art and design have intersected for many decades.

Learn more