The Hollywood blockbuster Kong: Skull Island (2017) portrays a group of explorers on a swampy island inhabited by giant, hostile creatures. A photojournalist, played by Brie Larson, often pauses to take a snapshot of the action. As she holds up her camera, we see the scene through her lens, tightly framed. And as the shutter clicks, the film freezes into a still picture. The message is clear: Photographs stop time, transforming the flux of experience into a fixed image.

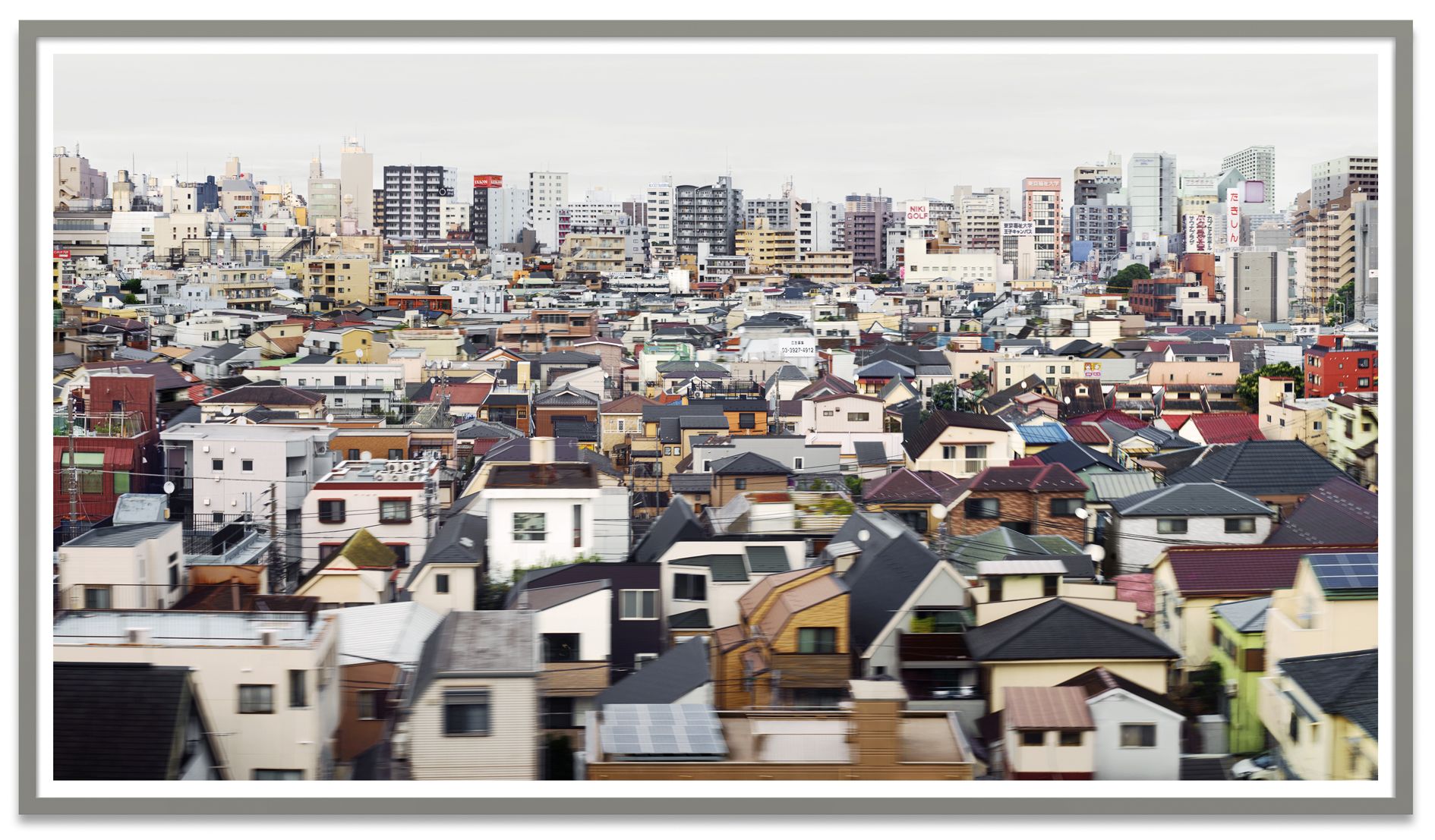

Andreas Gursky

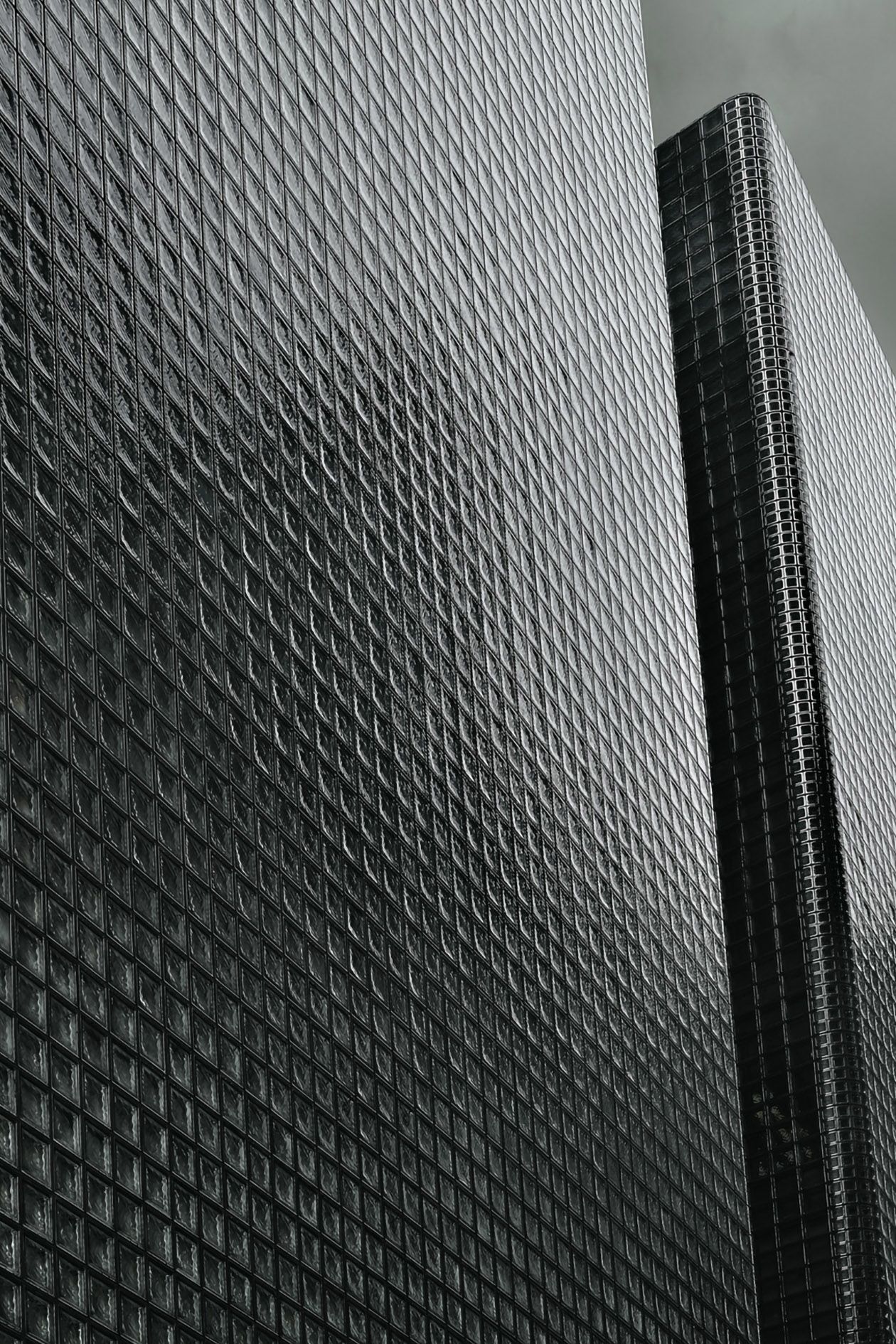

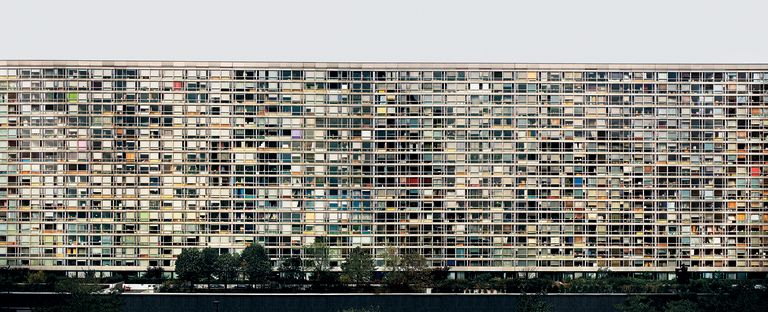

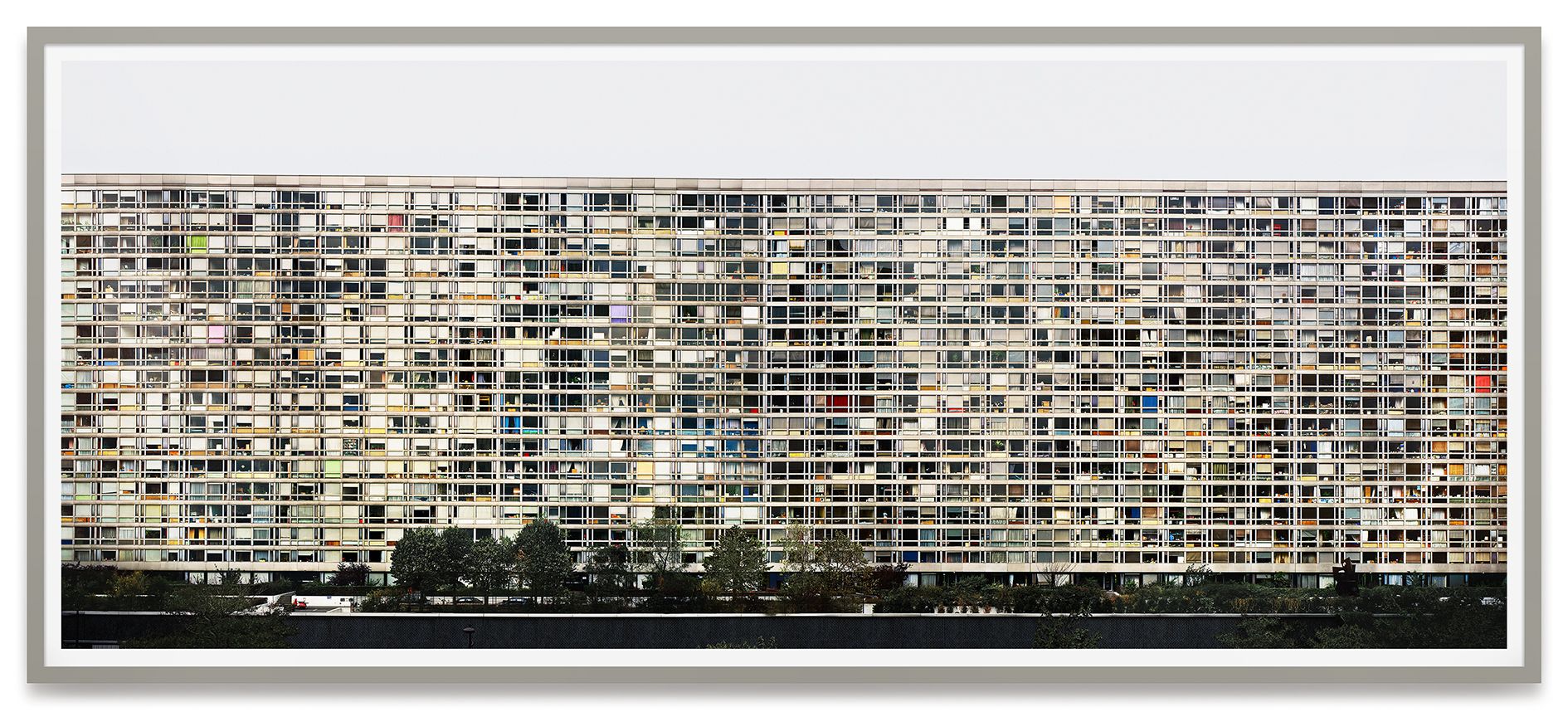

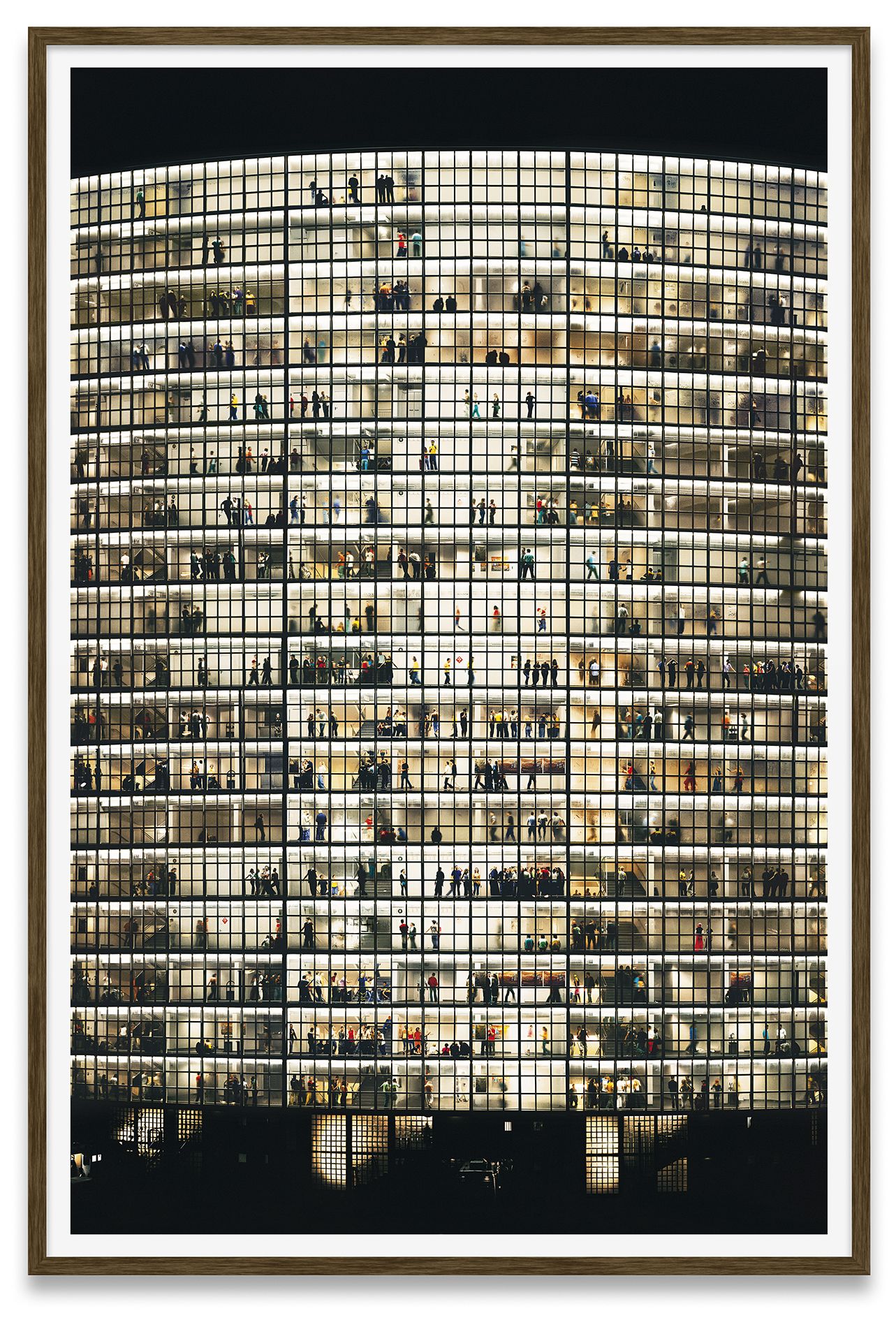

SH IV, 2014

Inkjet-print, Diasec

307 × 226 × 6.2 cm (framed)

120 7/8 × 89 × 2 3/8 inches (framed)