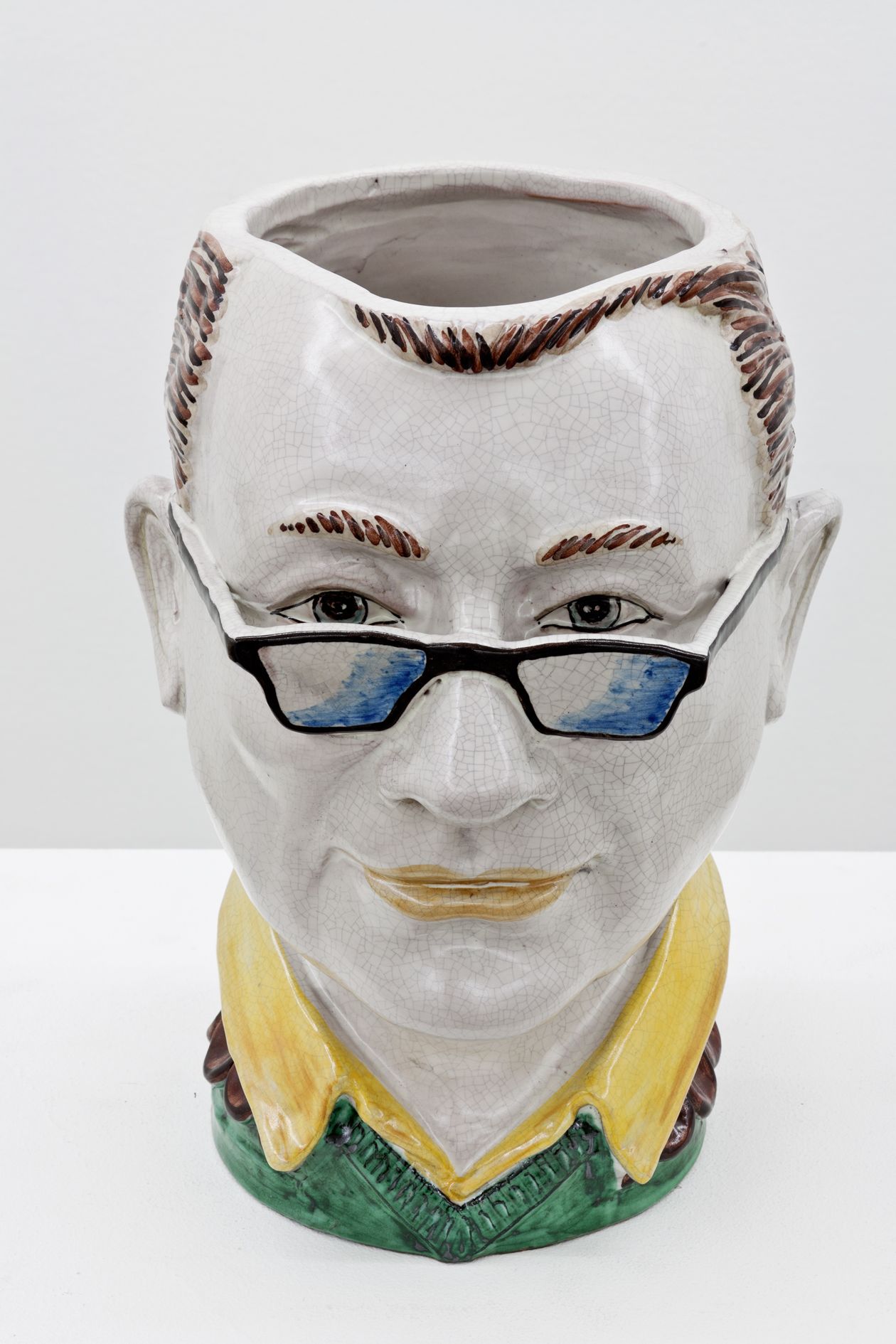

The arrangement is, no doubt, alluding to a famous collaborative piece of Gerhard Richter and Blinky Palermo, two influential Dusseldorf artists of a previous generation whose work for Schulze – having studied at Dusseldorf Academy, and today teaching there – inevitably is closely familiar, yet somewhat distant in timbre and sense of humor (though Blinky Palermo, with his romantic wit, certainly is less distant than the soberly determined Richter). Palermo had made a wall painting at Galerie Heiner Friedrich in Munich: He had painted one wall in so-called Munich yellow, a kind of ochre, with the exception of white stripes delineating the fringes; on the opposite wall, he reversed the order of colors (Wandmalerei auf gegenüberliegenden Wänden (Mural Painting on Opposite Walls, 1971)). Shortly after, in the Cologne space of Friedrich, Palermo extended the dominating yellow color on all of the room’s walls, while Richter contributed two bronze, face-cast portraits of himself and Palermo placed on slender, cubic man-size steles, all covered in grey oil paint and facing one another (Zwei Skulpturen für einen Raum von Palermo (Two Sculptures for a Room by Palermo, 1971)). It’s hard to decide whether the work is just provocatively flirting with self-aggrandizement or actually going a step further, towards a tongue-in-cheek self-entombment: Death masks suppressing a laugh. But in any case, in his cover version, Schulze replaces the theme of male artist friendship with narcissist tautology; the restrained lead grey of Richter’s sculptures with the joyously unrestrained, bright colors of the ceramics; Palermo’s heavy ochre with a type of pistachio reminiscent of 1970s bathroom appliances; and the poised calmness of the precursors’ collaboration with a psychedelic penchant for the aesthetically unclean.

In his survey exhibition at Museum Villa Merkel in Esslingen near Stuttgart, in the summer of 2014, Schulze has given the pot-head self-portrait yet another dimension. Taking advantage of the fact that the museum is housed in a former residential villa, Schulze positioned a large table in a central room, covered it with a Schulze-canvas-as-tablecloth and put seven of his heads onto it in a semi-circle. With each of the heads sporting different plants (geranium, sunflower, aloe vera, etc.) The effect is that of a welcome committee gone awry, or of an eccentric, run-down boutique hotel’s over-eager attempt to decorate.

That’s what’s so fascinating about Schulze: He is absolutely fearlessly uninterested in appearing cool and unassailable. He offers himself and his work up for all kinds of wacky associations. And yet it’s not just a joke. It’s sometimes so simple that people don’t understand it. And yet it does have depth—the cuteness or careful ugliness of many of his motifs are almost like smoke screens diverting from his formal painterly skills at “working space,” because to show these off would just be too embarrassingly pompous. Instead of aspiring to some kind of solemn aura, his is an interior transcendence, an “intranscendence” frustrating the desire for a beyond yet finding consolation precisely in the banality of existence. It’s a romanticism of the utterly unromantic, inward in a down-to-earth way, devoid of the big demonstrative gestures of doubt and transcendence. It’s intranscendence.