The other world within which Waters regularly circulates—the world of art, and its peculiar people, business and traditions—is another frequent subject of his pointed and poignant works. R.I.P. Mike Kelley (2014) eulogizes the celebrated artist, and friend of Waters, who died tragically in 2012 and played a crucial role in the history of contemporary art, particularly in Los Angeles. Kelley’s works cut to the core of the suburban American psyche, and several of his memorable sculptures involved cats. Waters’ homage, which gives a nod to several of Kelley’s own materials and approaches, consists of an urn for pet ashes that he sourced from a retailer and embellished with idiosyncratic additions, including an engraved heart.

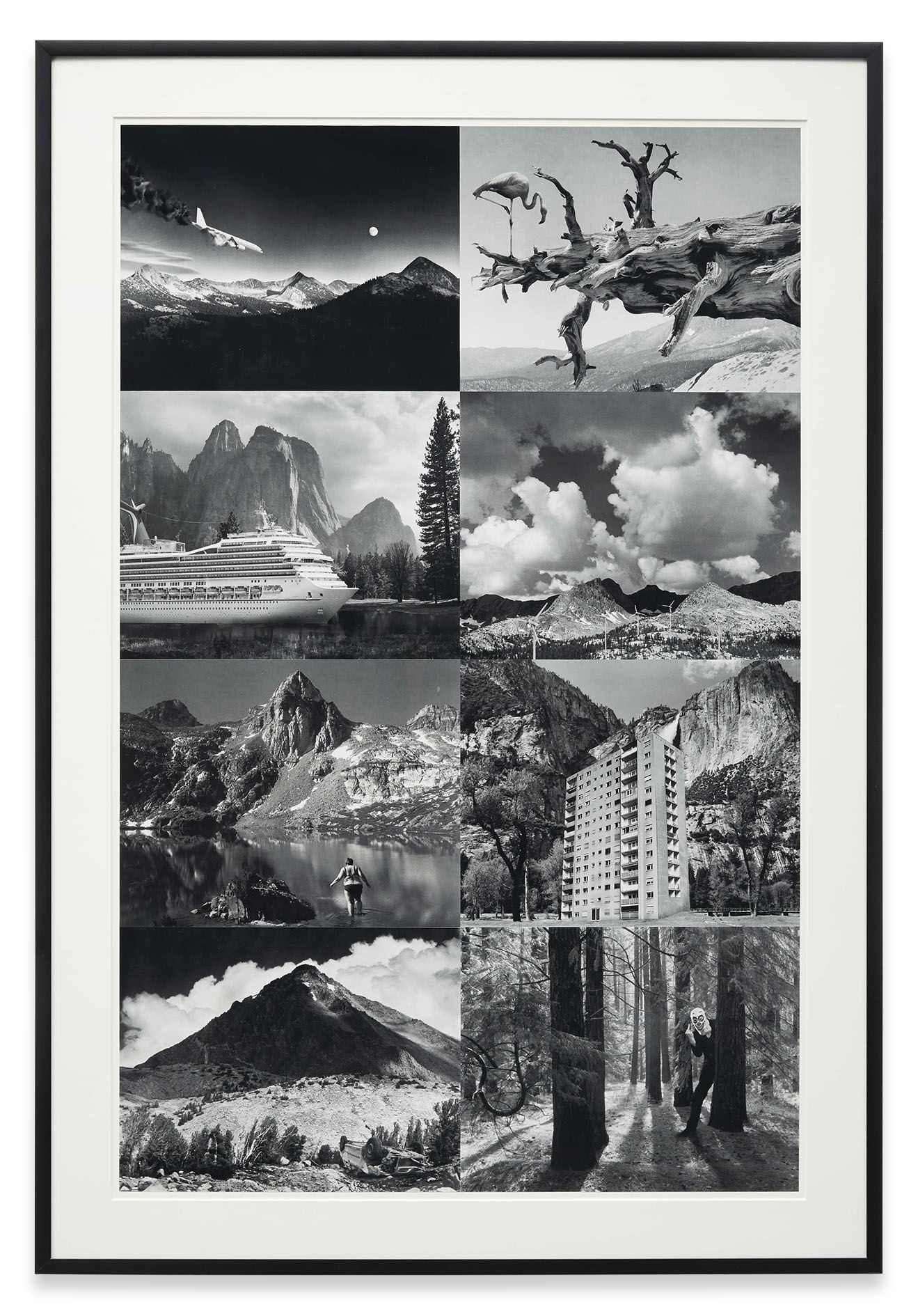

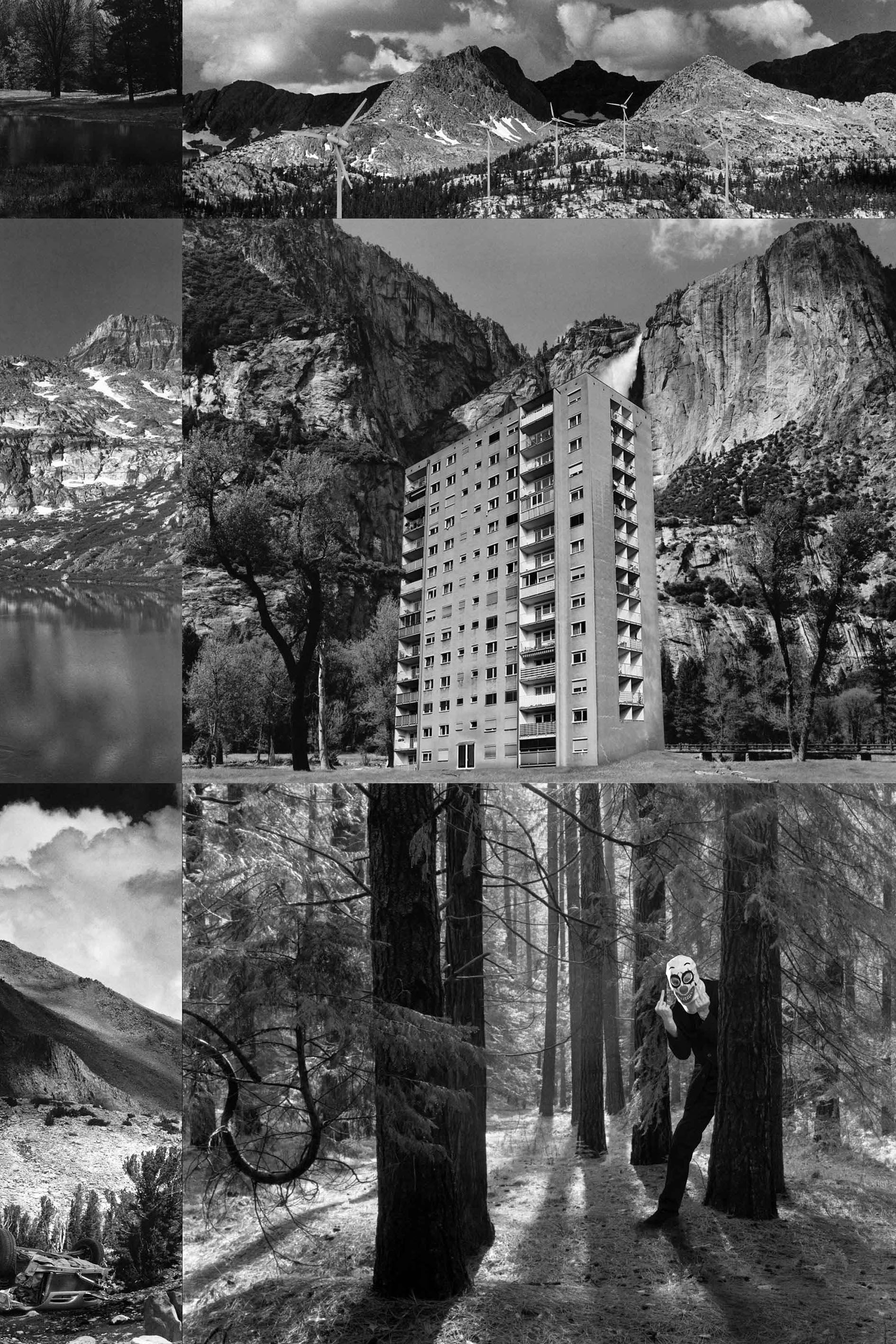

Cancel Ansel (2014) riffs on the work of another art figurehead, the photographer Ansel Adams, whose meticulous photographic techniques could not be farther from Waters’ own; where Adams used large-format cameras to capture pristine scenes of nature, Waters shoots pop culture straight from his television screen. Eight of Adams’ black-and-white landscapes are stacked together, and in each, the photographer’s beautiful scenery is puckishly defiled by Waters’ digital inclusions: A giant cruise liner sits in a serene mountain lake, wind turbines dot a majestic cloud-filled landscape, and an airplane, trailing smoke, descends dangerously into a valley below. Amid a sunlit grove of redwoods, a masked figure peaks out—Waters himself—giving the audience an obscene gesture.