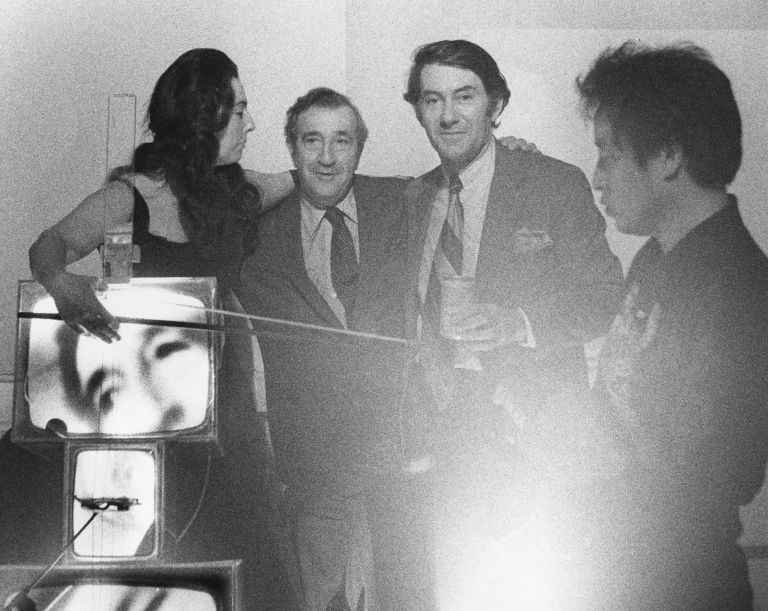

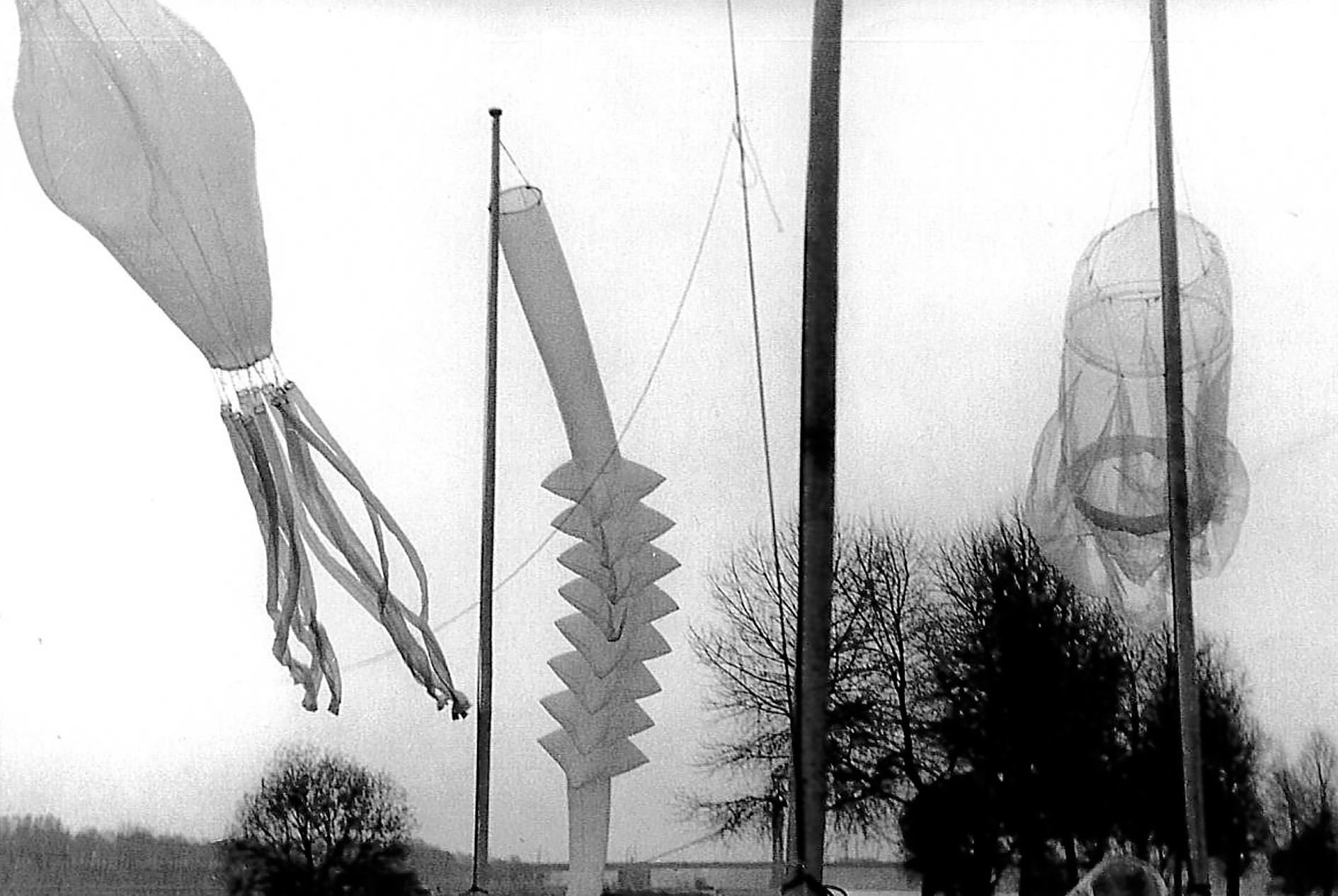

Otto Piene rose to prominence in the late 1950s as a founding member of the ZERO Group in Germany. After joining the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS), first as a fellow (1968–74) and later director (1974–94), the artist embarked on a new trajectory, expanding his oeuvre in terms of material, scope, collaboration and participation. He continued to divide his time between the United States and Europe, forging lasting connections with artists of myriad fields and approaches along the way.

The CAVS program followed in the interdisciplinary footsteps of institutions such as the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, as well as the program’s contemporary, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). Its goal, like that of its predecessors, was to bring together creative thinkers and practitioners of all backgrounds in an effort to expand the possibilities of both art making and technological advancement. CAVS fellows included artists as diverse as Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Yvonne Rainer, James Lee Byers and Peter Campus, and as CAVS' director, Piene was at the epicenter of this creative outburst.